We have all stood in the kitchen over a hot pan, cracked an egg, and performed the same nutritional ritual we were taught decades ago. We carefully toggle the shell back and forth, letting the clear protein slide into the bowl while trapping the yellow orb. Then, with a sense of virtuous discipline, we toss the yolk down the drain.

Table of Contents

For years, we believed this small act was saving our hearts. We thought we were dodging a bullet made of cholesterol. We were told that the white was the saint and the yolk was the sinner.

But for millions of Americans now facing liver health challenges, specifically those navigating liver fat accumulation, that yellow orb washing down the drain represents a massive missed opportunity. By discarding the yolk, you are throwing away one of the most potent weapons your body has to fight fat buildup in the liver.

This is not just about calories or macros. It is about a specific biochemical deficiency that is rampant in modern society. We are facing a silent epidemic of liver stress, and our dietary fear of the egg yolk may be contributing to it.

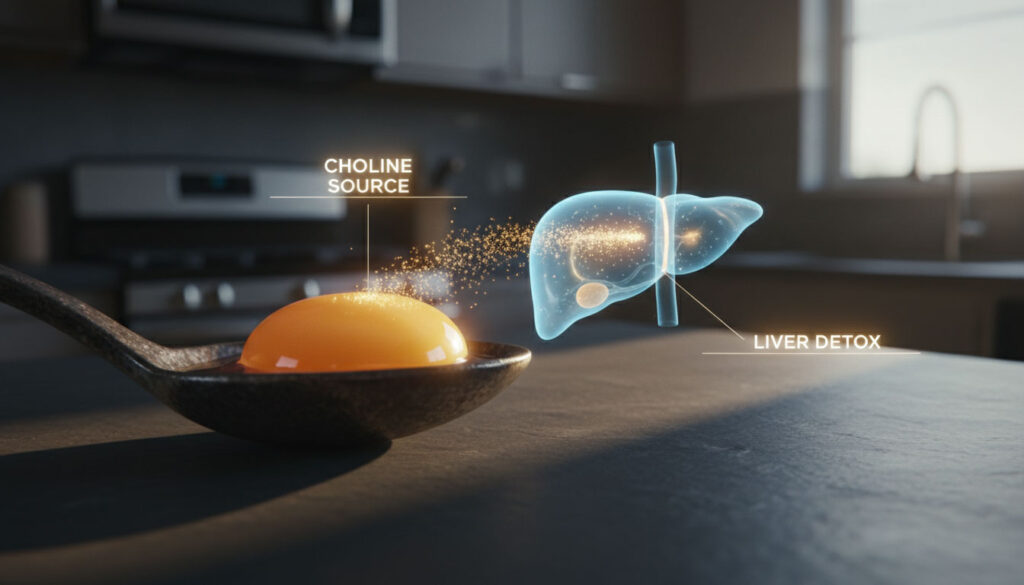

Are eggs bad for fatty liver? The short answer is no. In fact, discarding the yolk might be working against you. The choline content in eggs is concentrated almost entirely in the yolk. This nutrient is the biological key that starts the engine of fat metabolism in the liver. Without it, fat stays trapped.

This article peels back the outdated science of the 1980s. We will look at modern data from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the USDA to understand why the egg yolks cholesterol debate needs a serious update. It is time to stop fearing the yolk and start understanding the biochemistry of choline.

The Core Concept: Why We Started Tossing the Yolk

To understand the future of the fatty liver diet and eggs, we have to look at the past. The fear of the egg yolk is deeply rooted in the diet-heart hypothesis that gained traction in the mid-20th century.

The Era of Lipophobia and Outdated Guidelines

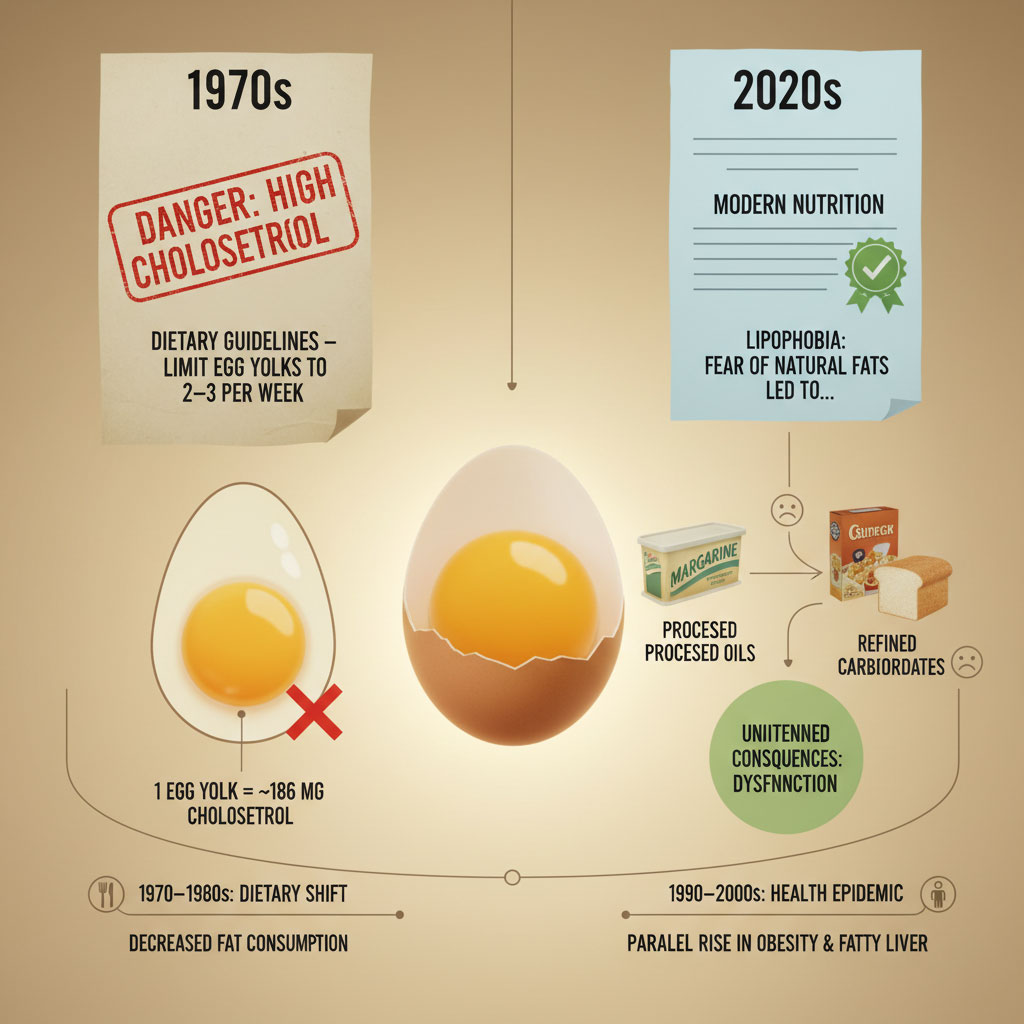

During the 1970s and 80s, health organizations declared war on dietary cholesterol. Since a single large egg yolk contains about 186 mg of cholesterol, it became public enemy number one. Doctors, dietitians, and government guidelines routinely advised patients to stick to egg whites or limit whole egg consumption to just two or three per week. The logic seemed sound at the time: if you eat less cholesterol, you will have less cholesterol in your blood.

This era was defined by “lipophobia,” or fear of fat. We replaced natural fats like butter and yolks with margarine and processed carbohydrates. Ironically, this dietary shift coincided with the explosion of metabolic diseases, including obesity and fatty liver.

The Shift in Nutritional Science

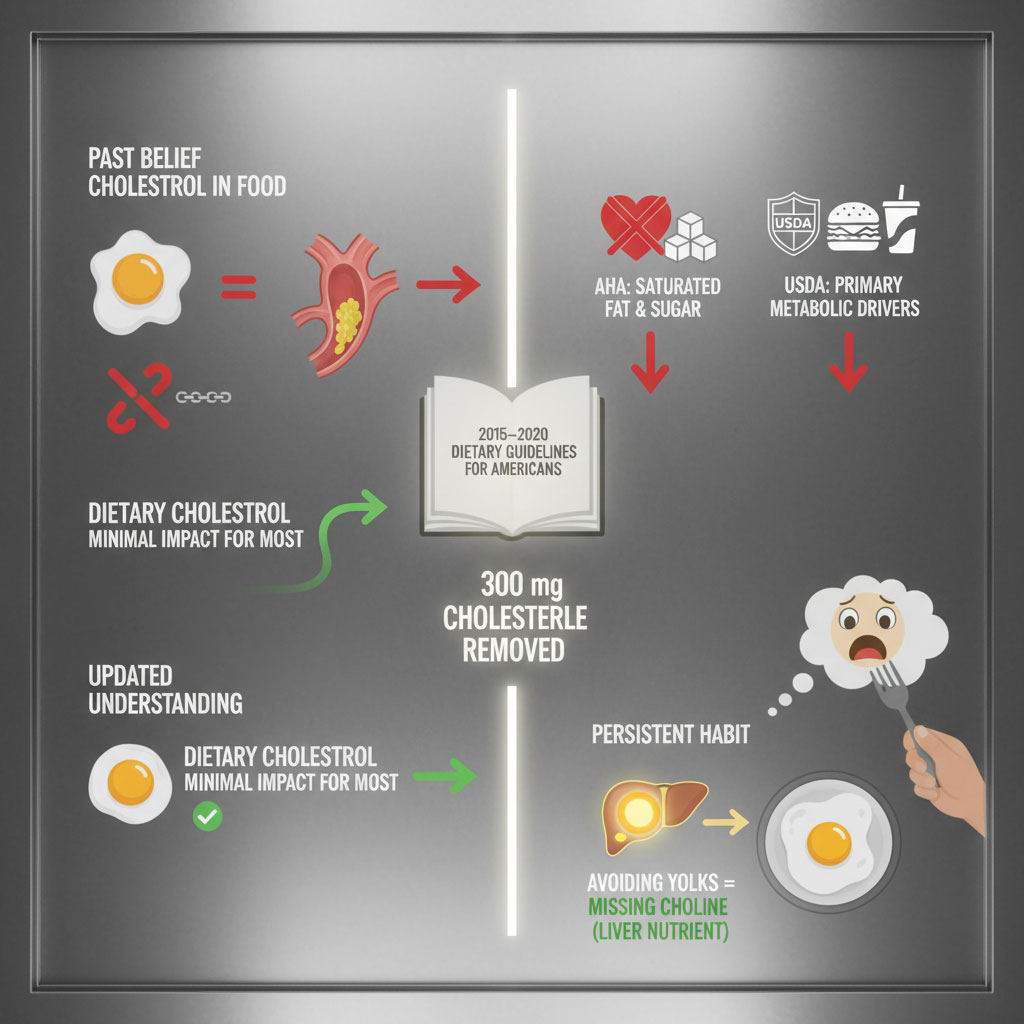

The narrative began to crumble with the release of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. After reviewing decades of data, the committee quietly removed the strict daily limit of 300 mg of dietary cholesterol. They admitted that for the vast majority of people, the cholesterol you eat does not directly translate to the cholesterol clogging your arteries.

The American Heart Association (AHA) and the USDA have since updated their stances. They now recognize that saturated fat and sugar are the primary drivers of heart disease and metabolic issues. Yet, the old habit of tossing the yolk persists in our kitchens. We still see “egg white omelets” framed as the healthy choice on brunch menus across the country.

This lag in public knowledge is dangerous. It is particularly harmful for those concerned about eggs and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), now increasingly referred to as Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). By holding onto outdated advice, patients are depriving themselves of the very nutrient required to heal their livers.

The Science of Choline: The Liver’s Unsung Hero

You might know that protein builds muscle or that calcium builds bone. But rarely do we talk about what builds a healthy liver. The answer is choline.

Choline is an essential nutrient that was only officially recognized by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. It is not a vitamin, but it acts like the B-complex vitamins. Its role in choline and liver fat metabolism is mechanical, vital, and non-negotiable.

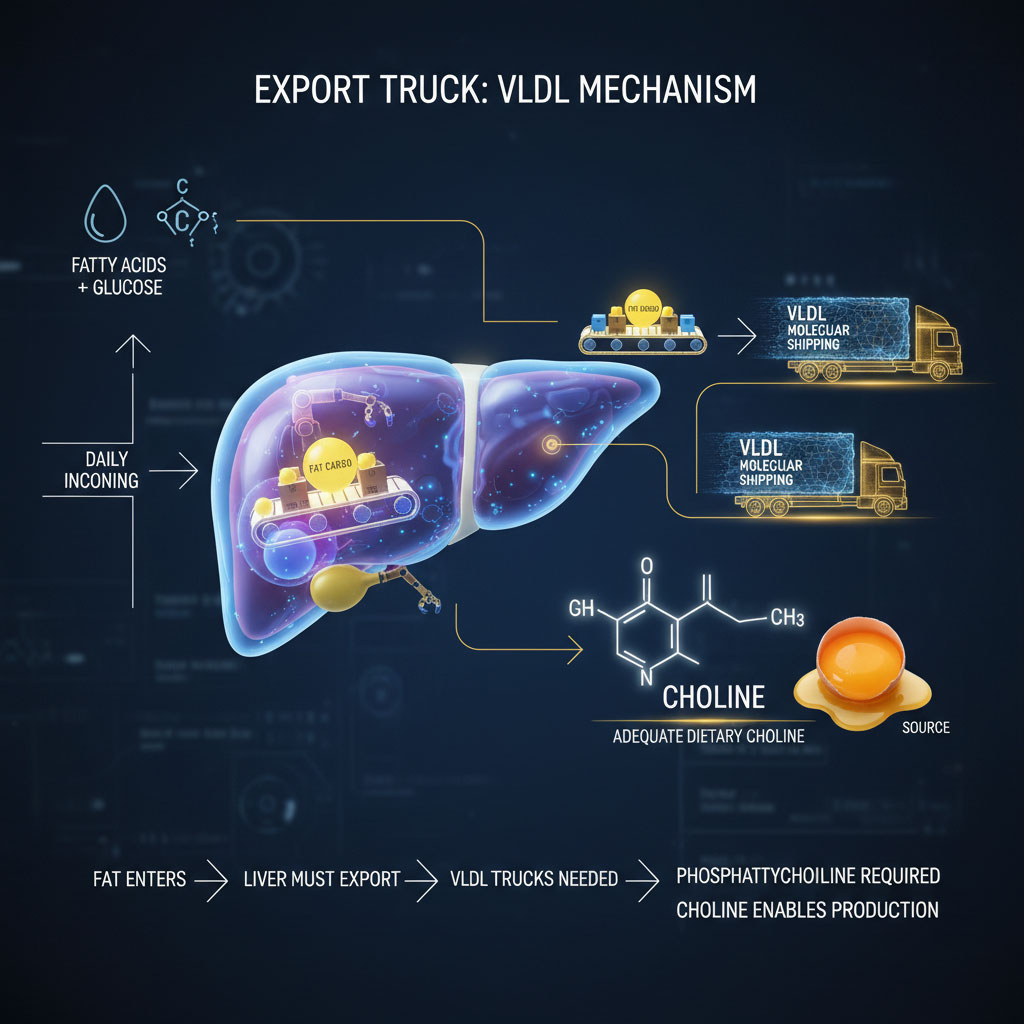

The “Export Truck” Mechanism: Understanding VLDL

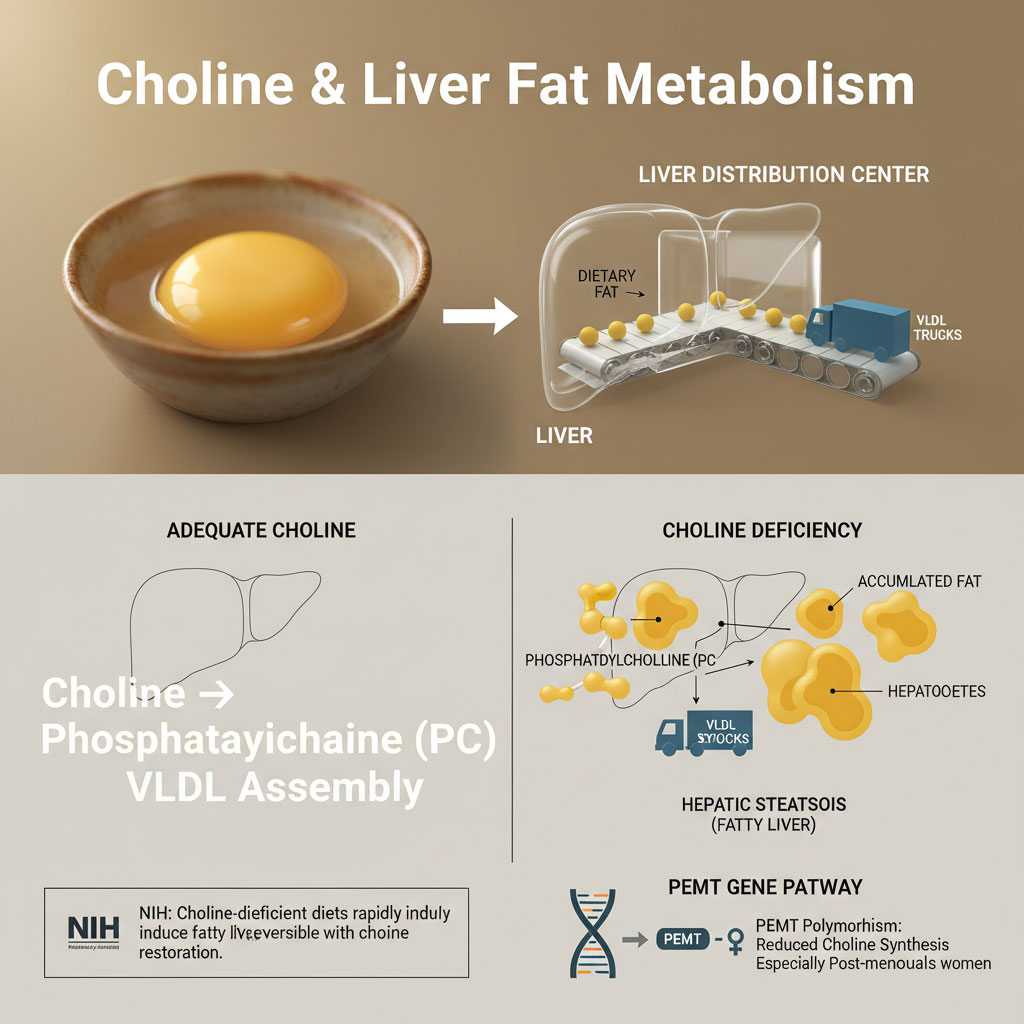

To understand why you need choline, you must understand what your liver does with fat. Think of your liver as a busy distribution warehouse. Every day, energy enters the warehouse in the form of fatty acids and glucose. For the liver to stay healthy, it must ship this fat back out to the rest of the body to be used as fuel or stored in adipose tissue.

The liver packages this fat into molecular shipping trucks called Very Low-Density Lipoproteins, or VLDL.

Here is the critical connection: The liver cannot build these VLDL trucks without a specific molecule called phosphatidylcholine. And the body cannot make enough phosphatidylcholine without dietary choline.

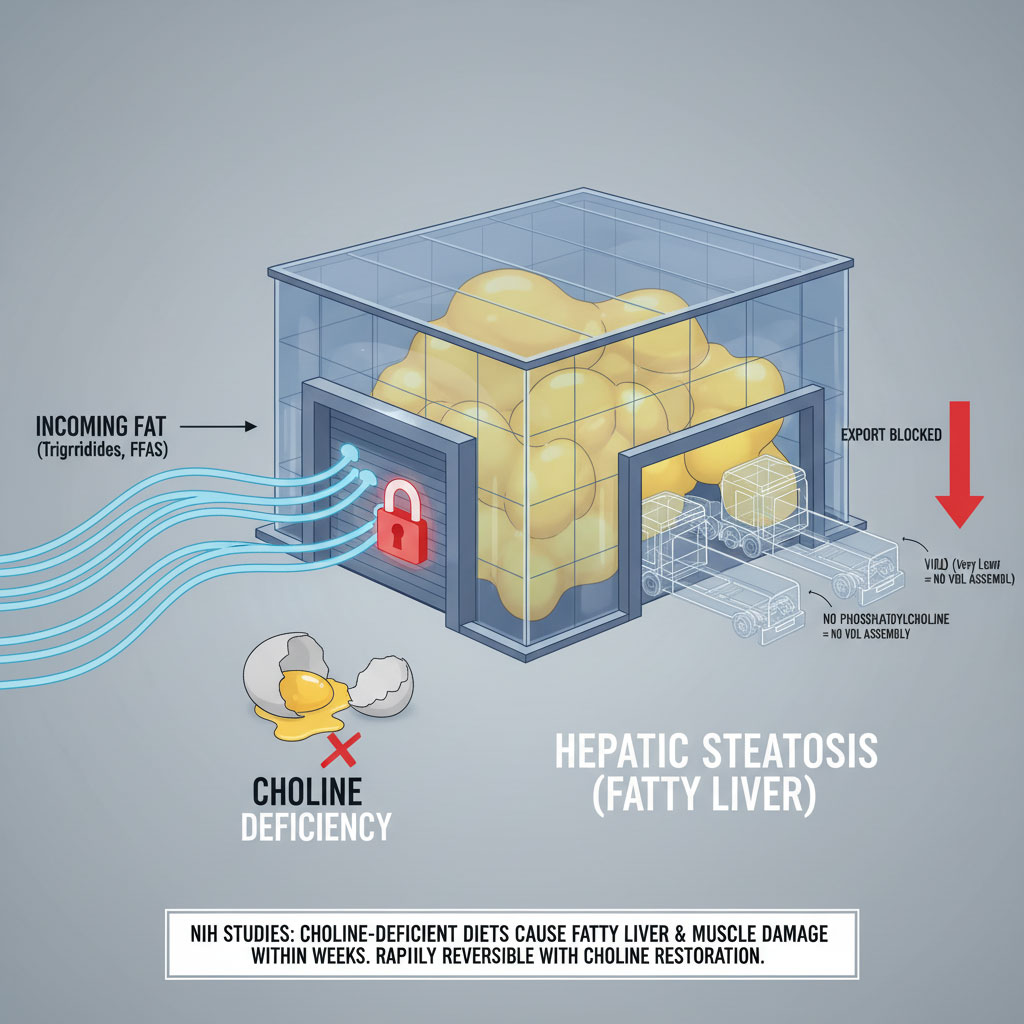

The Bottleneck of Deficiency

When you have a deficiency in choline, the process grinds to a halt. The liver still receives fat, but it cannot build the trucks to ship it out. The export dock shuts down. Fat begins to pile up inside the liver cells, known as hepatocytes. This accumulation is the biological definition of hepatic steatosis, or fatty liver.

The benefits of choline for liver health are immediate and measurable. NIH studies have demonstrated that when healthy adults are placed on a choline-deficient diet, they develop signs of fatty liver and muscle damage within weeks. It happens rapidly. When choline is reintroduced, the liver fat begins to clear.

When you toss the yolk, you are tossing the raw materials needed to build the trucks that clear fat from your liver. You are essentially closing the warehouse doors while the delivery trucks keep arriving.

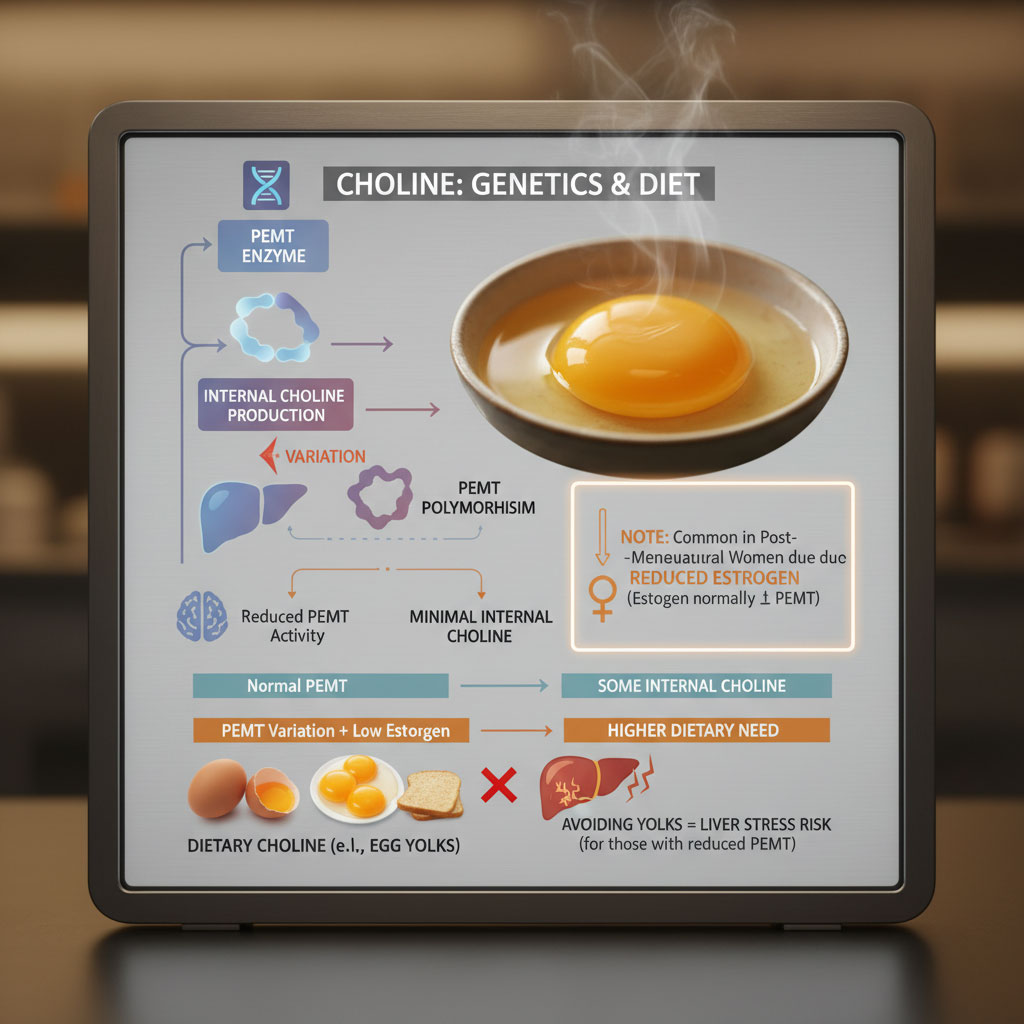

The Genetic Component: Why Some Needs Are Higher

It is important to note that not everyone produces choline efficiently. The body has a pathway to generate some choline internally through a gene called PEMT.

The PEMT Gene and Estrogen Connection

A significant portion of the population has a polymorphism, or a variation, in the PEMT gene that reduces their ability to produce choline endogenously. This is particularly common in post-menopausal women, who lose the estrogen that upregulates this gene.

For these individuals, dietary choline becomes even more critical. They cannot rely on their internal production. They must get it from food. And since eggs are the most potent source of bioavailable choline in the standard diet, avoiding yolks can be a direct path to liver stress for these individuals.

Nutritional Showdown: Egg White vs. Egg Yolk

There is a persistent myth that the egg white is the “healthy” part and the yolk is the “guilty” part. This is a massive oversimplification that ignores nutrient density.

The Egg White Profile: Protein Without Protection

The white is essentially an albumin delivery system. It is rich in protein, magnesium, and potassium. It is excellent for bodybuilding and calorie restriction. However, regarding liver health and dietary cholesterol, the white is biologically neutral. It provides building blocks for tissue but offers zero support for fat metabolism.

The Yolk Profile: The Metabolic Powerhouse

The yolk is where the magic happens. It contains 100% of the egg’s fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and essential fatty acids. Most importantly, it houses the choline content in eggs.

Let’s look at the hard data to settle the egg whites vs yolks cholesterol debate.

| Nutrient (per Large Egg) | Egg White (The “Safe” Option) | Egg Yolk (The “Feared” Option) | Impact on Liver Health |

| Choline | ~0.4 mg | ~147 mg | Critical for fat export (VLDL secretion). |

| Cholesterol | 0 mg | ~186 mg | Essential for cell membrane repair & bile production. |

| Protein | ~3.6 g | ~2.7 g | Necessary for tissue regeneration. |

| Vitamin A | 0 IU | ~240 IU | Antioxidant protection against inflammation. |

| Vitamin D | 0 IU | ~41 IU | Linked to lower severity of NAFLD. |

| Fat | ~0 g | ~4.5 g | Provides satiety and absorption of vitamins. |

As the table demonstrates, relying solely on egg whites completely removes the specific nutrients that support the liver. You get the protein, but you miss the metabolic signaling that prevents hepatic steatosis.

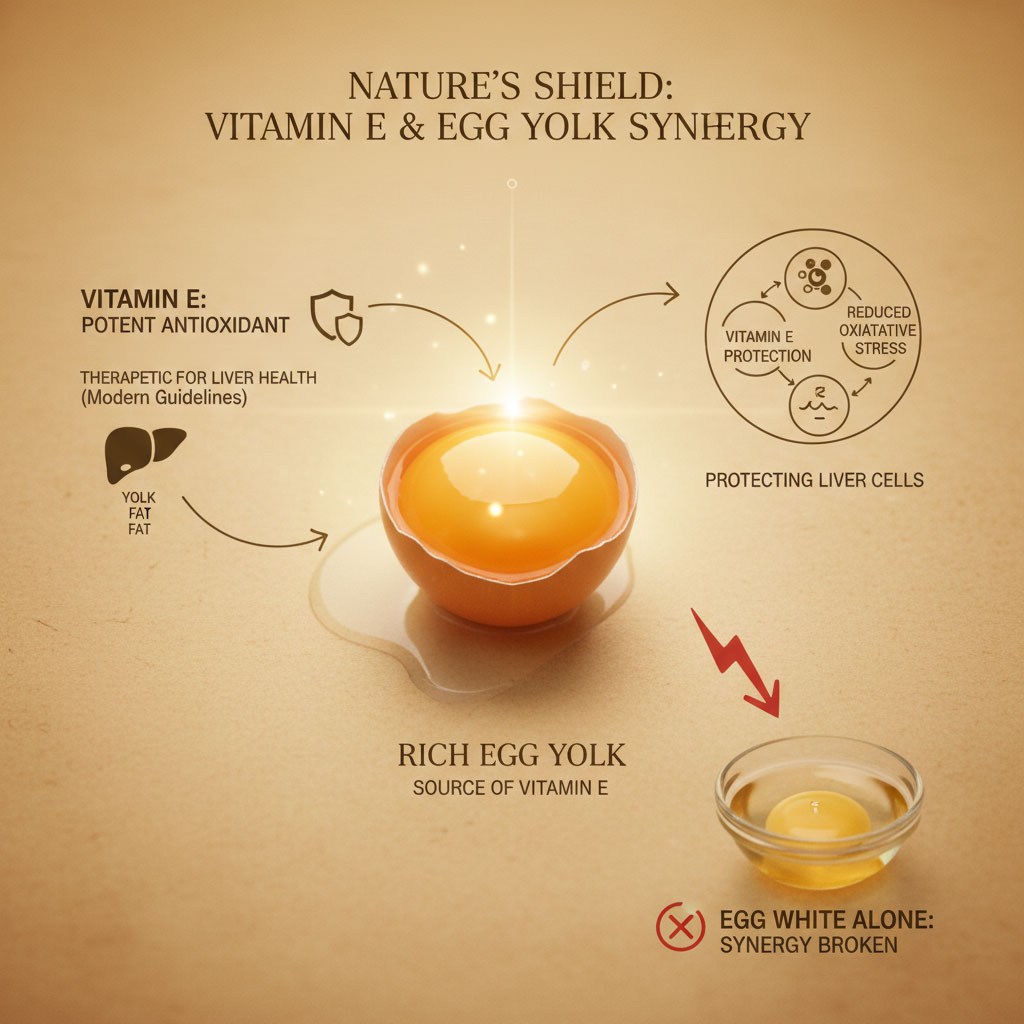

The Synergy of Vitamin E and Fats

Beyond choline, the yolk contains Vitamin E. This is crucial because recent guidelines for the treatment of liver inflammation specifically list Vitamin E as a therapeutic agent. It is a powerful antioxidant that protects liver cells from oxidative stress. Nature packaged the fat (yolk) with the antioxidant needed to protect that fat (Vitamin E). When we separate them, we lose that synergy.

Addressing the Elephant in the Room: Cholesterol & Heart Risk

Even with the data on choline, many patients ask: are eggs bad for fatty liver if I also have high cholesterol?

This is a valid concern, and it deserves a nuanced answer. We need to distinguish between dietary cholesterol (what you eat) and blood cholesterol (what circulates in your veins).

The Homeostasis Mechanism: How the Liver Adapts

Your liver creates cholesterol every day because your body needs it. Cholesterol is not a poison; it is a structural necessity. It is used to produce sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen, it is the precursor to Vitamin D, and it is the primary component of bile acids, which you need to digest food.

The liver is smart. It operates on a feedback loop known as homeostasis. When you consume more egg yolks cholesterol, your liver detects the influx and simply produces less of its own. It balances the ledger. Conversely, when you eat zero cholesterol, your liver ramps up production to meet the body’s demands.

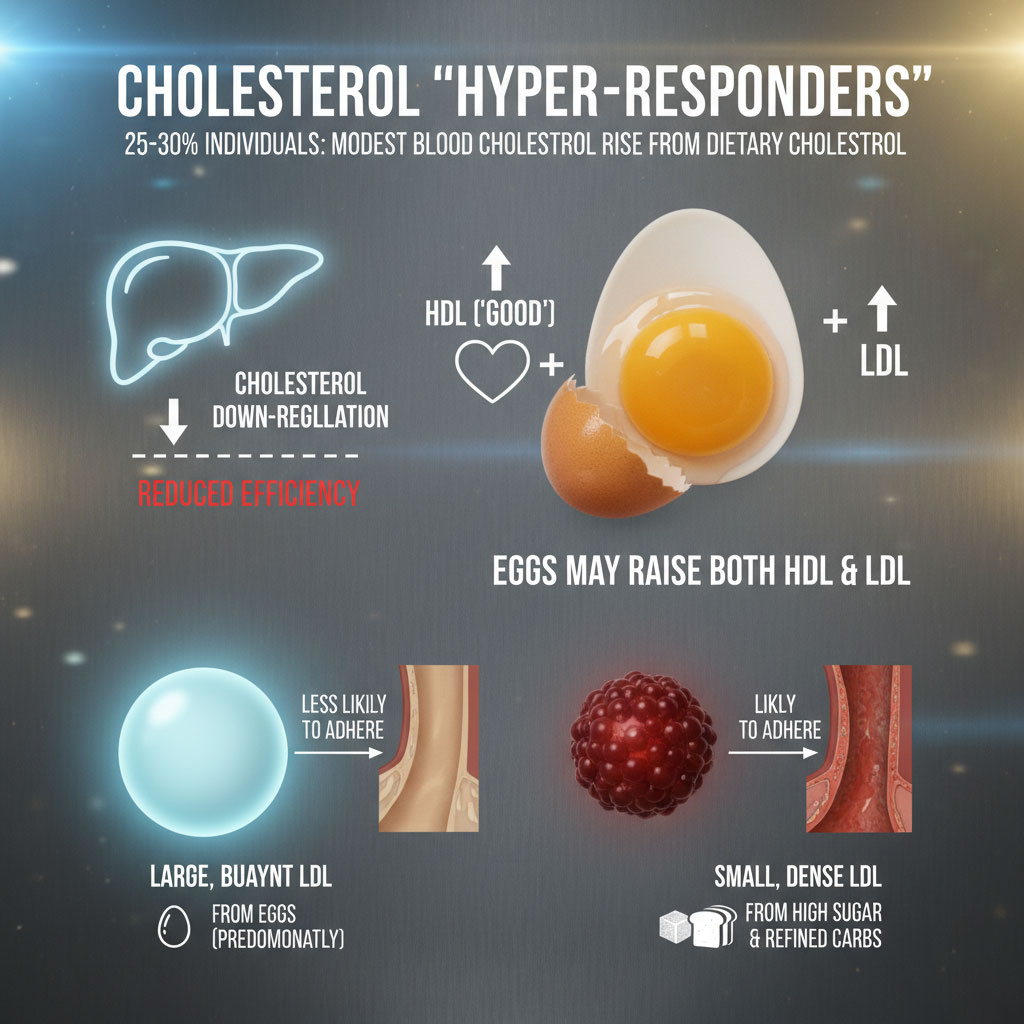

The Hyper-Responder Nuance

There is a genetic subset of the population, roughly 25% to 30%, known as “hyper-responders.” For these individuals, dietary cholesterol does cause a modest rise in blood cholesterol levels. They do not down-regulate production as efficiently as others.

However, context is everything. Research shows that when eggs raise cholesterol in these individuals, they tend to raise both HDL (the “good” cholesterol) and LDL. Furthermore, the type of LDL matters. The LDL particles tend to be large and buoyant rather than small and dense. Large LDL particles are biologically different; they are less likely to stick to arterial walls and cause plaque compared to the small, dense type caused by high sugar and refined carbohydrate intake.

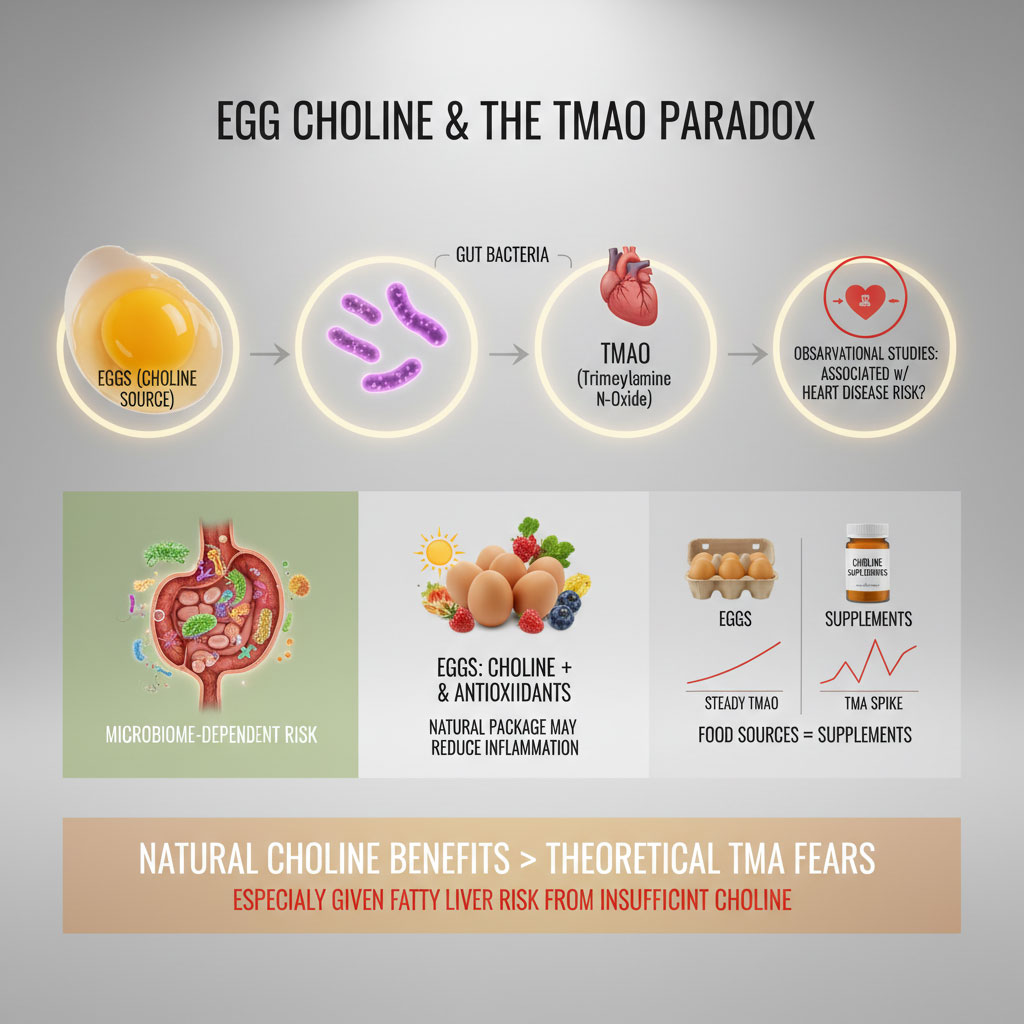

TMAO: The Counter-Argument and Context

Some researchers have raised concerns about a compound called Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). When gut bacteria digest choline, they produce TMAO, which has been linked to heart disease risk in some observational studies. This is often the argument used to discourage meat and egg consumption.

However, this risk appears to be highly context-dependent and related to the overall microbiome health. The choline content in eggs comes packaged with other nutrients like Vitamin D and antioxidants that may mitigate inflammatory effects. Furthermore, studies comparing eggs to choline supplements often find that the food source does not spike TMAO in the same way. Most experts agree that for the general population, the benefits of natural food sources of choline far outweigh the theoretical risks of TMAO, especially when compared to the tangible, immediate risk of fatty liver progression.

The Insulin Connection: Why Eggs Are Metabolic Medicine

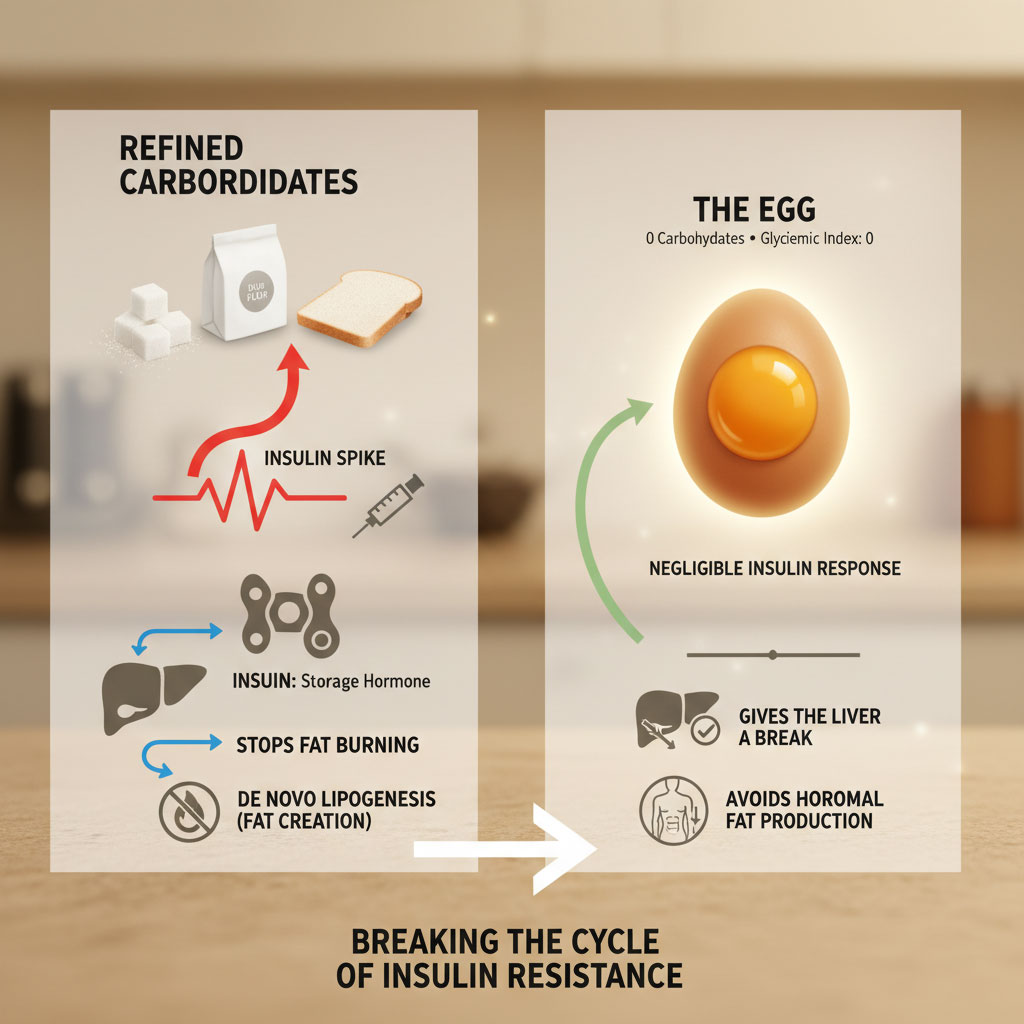

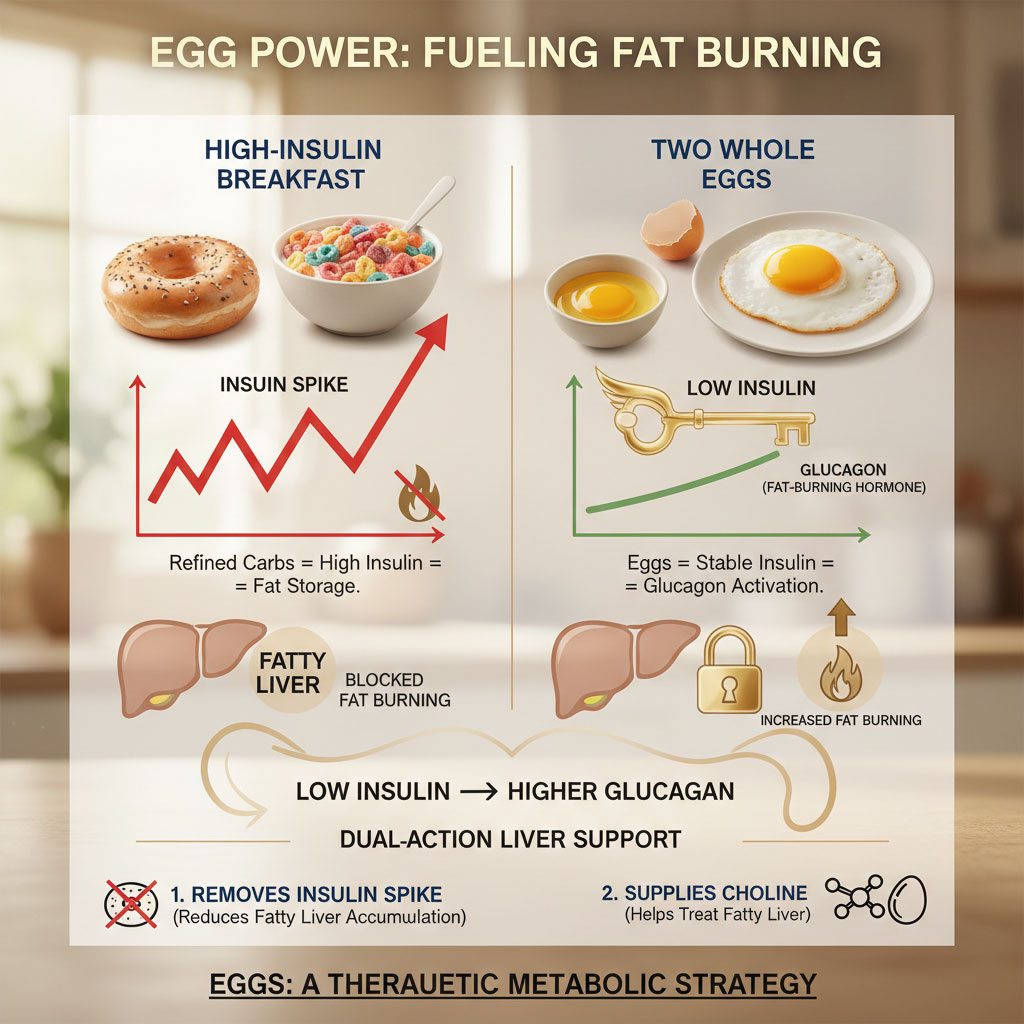

When discussing fatty liver, we cannot ignore insulin. The root cause of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) is rarely dietary cholesterol; it is almost always insulin resistance.

Breaking the Cycle of Insulin Resistance

When you eat carbohydrates, specifically sugar and refined flour, your insulin levels spike. Insulin is a storage hormone. High levels of insulin tell the liver to stop burning fat and start creating it, a process called de novo lipogenesis.

Eggs contain zero carbohydrates. They have a glycemic index of zero. When you eat an egg, there is negligible insulin response. This gives the liver a break.

Glucagon and Fat Burning

By consuming a low-insulin food like eggs, you allow a counter-hormone called glucagon to rise. Glucagon is the “fat-burning” hormone. It signals the liver to release stored energy.

Therefore, including whole eggs in your diet is not just about getting choline; it is about displacing the foods that are actually hurting you. If you eat two eggs for breakfast instead of a bagel or cereal, you have removed the insulin spike that drives fatty liver while simultaneously providing the choline that treats it. It is a dual-action therapeutic strategy.

Practical Strategies: How to Eat Eggs for Fatty Liver Recovery

Knowing the science is one thing. Putting it into practice on your plate is another. If you are asking, “can eating eggs worsen fatty liver disease?” the answer often lies in how you cook them and what you eat them with.

Quantity: The Golden Ratio

So, how many eggs can a person with fatty liver safely eat per week?

Current consensus from liver health nutritionists suggests that for most people with NAFLD, eating 7 to 12 eggs per week is safe and beneficial. This averages out to about 1 to 2 eggs per day.

If you are a known hyper-responder with difficult-to-manage cholesterol, you might limit this to 3 or 4 yolks per week while supplementing with additional whites for protein. However, cutting yolks entirely is rarely recommended anymore, as the nutritional loss is too great.

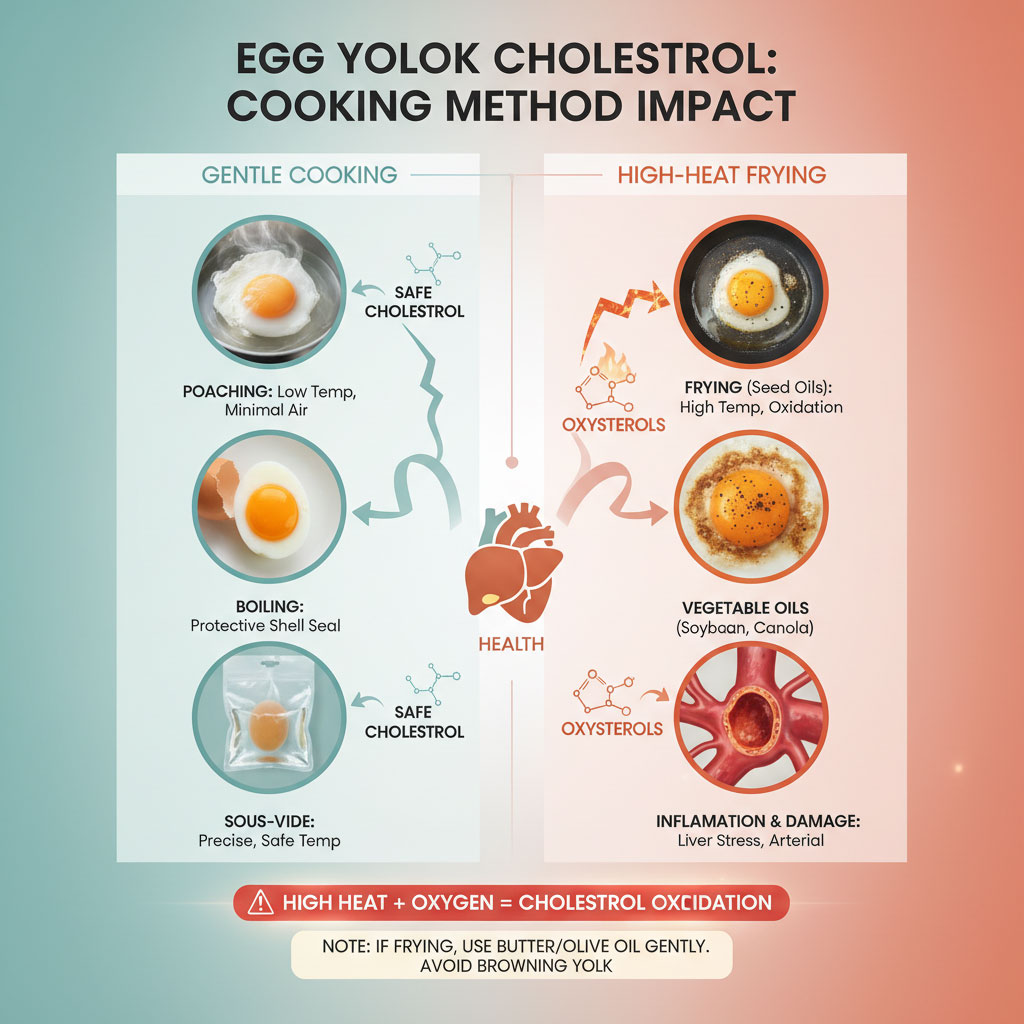

Cooking Methods: The Danger of Oxidation

This is the most critical practical tip in this entire article. The cholesterol in the yolk is safe until you damage it with high heat.

Understanding Oxysterols

Cholesterol is a lipid. Like all fats, it can oxidize. When you fry an egg in vegetable oil until the edges are crispy and brown, or when you scramble eggs over high heat until they are rubbery, the cholesterol can oxidize.

Oxidized cholesterol creates compounds called oxysterols. Unlike natural cholesterol, oxysterols are inflammatory. They can contribute to liver stress and arterial damage.

The Best Methods: Poaching and Boiling

To maximize the benefits of choline for liver health, use gentle cooking methods:

- Poaching: This is the gold standard. It keeps the temperature low (100°C/212°F max) and preserves the nutrients. The yolk remains shielded from direct air exposure.

- Boiling: Hard or soft-boiled eggs are excellent. The shell acts as a hermetic seal, protecting the fats inside from oxidation during the cooking process.

- Sous-vide: This precision cooking method keeps the eggs at a very specific, safe temperature.

The Worst Methods: High-Heat Frying

Avoid frying eggs in vegetable seed oils (like soybean or canola oil) at high heat. The combination of oxidized oil and oxidized cholesterol is a double blow to the liver. If you must fry, do it gently in butter or olive oil, and do not let the yolk harden or brown.

Dietary Context: What to Eat With Your Eggs

Eating eggs every day with fatty liver is beneficial if the rest of the diet supports it. We must stop looking at foods in isolation.

Eating two eggs with a side of processed bacon, hash browns, and white toast is a net negative. The benefits of the eggs are overwhelmed by the inflammatory fats in the bacon and the insulin spike from the potatoes and bread.

Eating two poached eggs over a bed of sautéed spinach with a slice of avocado and a side of berries is a liver-healing super meal. The fiber in the vegetables helps bind to excess cholesterol in the gut, ensuring it is excreted rather than reabsorbed. The antioxidants in the greens work with the Vitamin E in the egg. The choline in the egg supports fat export. This is nutritional synergy.

Choline Sources: Eggs vs. Supplements vs. Other Foods

While we are focusing on eggs, they are not the only source of choline. However, they are often the most accessible, affordable, and bioavailable source.

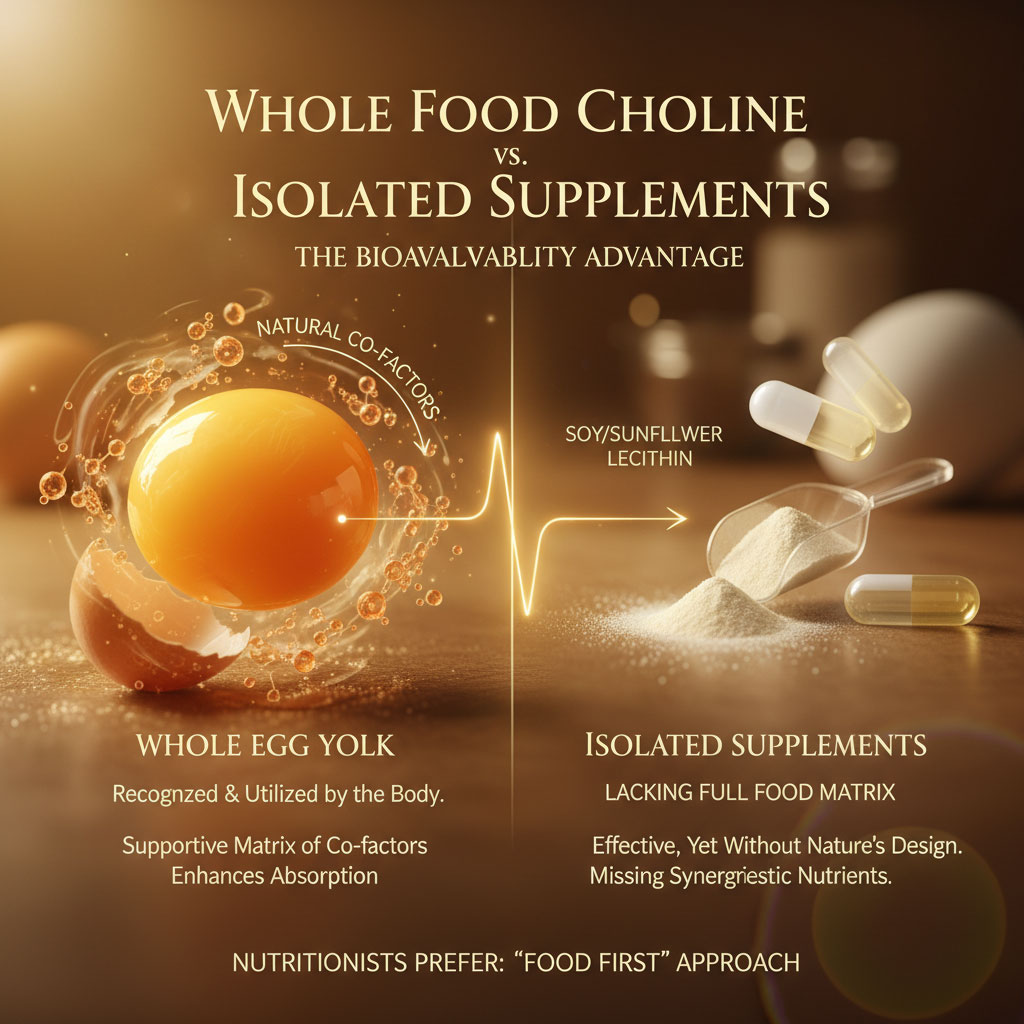

The Bioavailability Factor

You can buy phosphatidylcholine supplements, often derived from soy or sunflower lecithin. While these can be effective and are sometimes used in clinical protocols, nutritionists generally recommend a “food first” approach. Whole foods contain a matrix of co-factors that help absorption. The body recognizes food differently than isolated synthetic nutrients.

Comparison of Sources

Let’s verify where eggs stand in the hierarchy of choline-rich foods.

| Food Source (100g serving) | Choline Content (mg) | Pros for Fatty Liver | Cons for Fatty Liver |

| Beef Liver | ~400 mg | Highest concentration | High in purines and Vitamin A (toxicity risk if overeaten daily). |

| Hard Boiled Egg | ~250 mg (approx 2 eggs) | Perfect bio-availability | Cholesterol concern for specific hyper-responders. |

| Salmon | ~90 mg | High Omega-3s | Lower choline density than eggs. |

| Soybeans | ~116 mg | Good plant-based option | Contains phytoestrogens; harder to digest for some. |

| Choline Bitartrate (Supp) | Varies | Easy to consume | Low absorption rate; lacks synergistic nutrients. |

Safe egg intake for fatty liver patients is often easier to achieve than eating beef liver daily. Most people do not enjoy the taste of organ meats, and eating liver every day can lead to Vitamin A toxicity (hypervitaminosis A). Eggs provide a practical, daily vehicle for getting your 425-550 mg of required choline without the risk of heavy metal toxicity or vitamin overload associated with organ meats.

Case Studies and Real Data

The correlation between egg consumption and NAFLD risk has been studied extensively in recent years, challenging the old dogmas.

The China Study Data

Large-scale observational studies from China, involving hundreds of thousands of participants, have found that moderate egg consumption (about one per day) was associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events compared to those who ate no eggs. While this is heart data, it supports the safety profile regarding cholesterol. Furthermore, specific analyses regarding liver health in Asian populations have shown that egg consumption does not correlate with increased liver fat when adjusted for overall caloric intake.

NHANES Data and The Deficiency Crisis

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the US reveals a startling statistic: Roughly 90% of Americans are not meeting the adequate intake for choline.

This widespread deficiency correlates almost perfectly with the rising rates of fatty liver disease. It is a silent epidemic. When researchers look at fatty liver diet and eggs, they often find that patients with the lowest choline intake have the highest liver fat content and the most progression toward fibrosis.

Clinical Instances

In clinical settings, functional medicine practitioners often see improvements in liver enzymes (ALT and AST) when patients switch from a high-sugar, processed diet to a whole-food diet that includes quality proteins like eggs. The choline content in eggs acts as a lipotropic agent, actively helping to decongest the liver. Patients often report better energy levels and satiety, which helps them stick to the rest of their dietary plan.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The days of fearing the yolk should be over. The evidence is clear that for the vast majority of people, the nutritional benefits of the whole egg far outweigh the risks of dietary cholesterol. We cannot afford to ignore a nutrient as vital as choline while facing a liver health crisis.

If you are navigating eggs and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), remember these key points:

- Stop Tossing the Yolk: The yolk contains the choline needed to ship fat out of your liver. The white is just protein; the yolk is the medicine.

- Choline is Critical: Without adequate choline, your liver cannot process fats, leading to hepatic steatosis. It is the bottleneck of liver metabolism.

- Cook Gently: Avoid frying at high temperatures. Boil, poach, or gently scramble your eggs to prevent cholesterol oxidation, which preserves the integrity of the fats.

- Monitor Quantity: Eating eggs every day with fatty liver (1-2 daily) is generally safe, effective, and recommended by modern nutritional standards.

- Food First: Prioritize choline content in eggs over supplements for better absorption and nutrient synergy. Use eggs to replace high-carb breakfast options like bagels or cereal.

Your liver is a resilient organ. It has the incredible ability to regenerate if given the right tools. Choline is one of the most important tools in that toolkit. Next time you crack an egg, save the yolk. You might just be saving your liver.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Can eating eggs worsen fatty liver disease?

No, eating eggs typically does not worsen fatty liver disease. In fact, the choline found in egg yolks is essential for liver function and helps export fat from the liver. The misconception comes from outdated cholesterol fears. However, it is best to avoid deep-fried eggs or eating them with processed meats, as the accompanying fats are the real issue.

How much choline is in an egg yolk?

One large egg yolk contains approximately 147 mg of choline. This provides a significant portion of the daily adequate intake, which is 550 mg for men and 425 mg for women. Eating two eggs gets you more than halfway to your daily goal.

Is it safe to eat egg yolks with fatty liver?

Yes, it is safe and recommended. The yolk provides phosphatidylcholine, which is critical for preventing fat accumulation in liver cells. Discarding the yolk removes this benefit and leaves you with only protein, missing the metabolic support your liver needs.

Does egg cholesterol affect liver fat accumulation?

Current research indicates that dietary cholesterol has a minor impact on liver fat accumulation compared to added sugars, fructose, and saturated fats. Sugar is the primary driver of lipogenesis (fat creation) in the liver. The cholesterol in eggs is used for cellular repair.

What is the best way to cook eggs for liver health?

The best methods are poaching, boiling, or sous-vide. These gentle cooking methods prevent the cholesterol in the yolk from oxidizing. Oxidized cholesterol can be inflammatory to the liver, so avoiding crispy, brown edges on fried eggs is a smart strategy.

Can I eat eggs every day if I have NAFLD?

Yes, current evidence suggests that consuming 1–2 whole eggs per day is safe for most patients with NAFLD. It ensures a steady supply of choline to support liver metabolism. If you have severe genetic high cholesterol, consult your doctor, but for most, it is beneficial.

Are egg whites better than yolks for the liver?

No. While egg whites are a good source of lean protein, they lack choline entirely. To get the liver-protective benefits, you must consume the yolk. The white helps muscle; the yolk helps the liver.

Do eggs raise enzymes like ALT and AST?

Generally, no. A diet rich in whole foods, including eggs, often helps lower liver enzymes over time by reducing liver fat. High enzymes are more commonly caused by alcohol, sugar, and excess weight. Improving the liver’s ability to export fat via choline can help normalize these numbers.

Is choline from supplements as good as choline from eggs?

Whole food sources like eggs are generally preferred. They offer better bioavailability and contain synergistic nutrients like Vitamin E, Selenium, and Omega-3s that supplements often lack. Food provides a complex matrix that the body absorbs efficiently.

What if I have both fatty liver and high cholesterol?

If you have both conditions, consult your doctor regarding your specific lipid markers. However, a moderate intake of 3–4 yolks per week, combined with plenty of fiber and vegetables, is usually permitted and safe. Often, fixing the fatty liver improves the cholesterol numbers naturally.

Does the type of egg (organic vs. conventional) matter?

Yes. Pasture-raised or Omega-3 enriched eggs typically have higher levels of anti-inflammatory fatty acids and Vitamin E compared to conventional eggs. Since reducing inflammation is key to treating fatty liver, these eggs are a superior choice if your budget allows.

What foods should I avoid eating with eggs?

To keep your meal liver-friendly, avoid pairing eggs with processed meats like sausage or bacon, and avoid refined white bread or sugary pastries. Instead, pair eggs with spinach, avocado, berries, or whole-grain toast to add fiber and antioxidants.