You have likely stood in your kitchen at 7 AM or in the grocery aisle staring at a nutrition label and wondering exactly how to divide your day. We are often told the total number of calories to consume but rarely told how to spend them. It is one thing to know you need 2,000 calories a day. It is an entirely different challenge to know if you should eat 800 of them at breakfast or save them for a family dinner.

Table of Contents

The frustration with standard diet advice is that it treats every human body like the same machine. But your metabolism is not a calculator that resets at midnight. It is a complex adaptive system influenced by your hormones, your job description, and even the time on the clock. For decades, the nutritional narrative has been dominated by the simple “calories in vs. calories out” model. While the total number matters, the distribution of that energy plays a massive role in how you feel, how you sleep, and how effectively you burn fat.

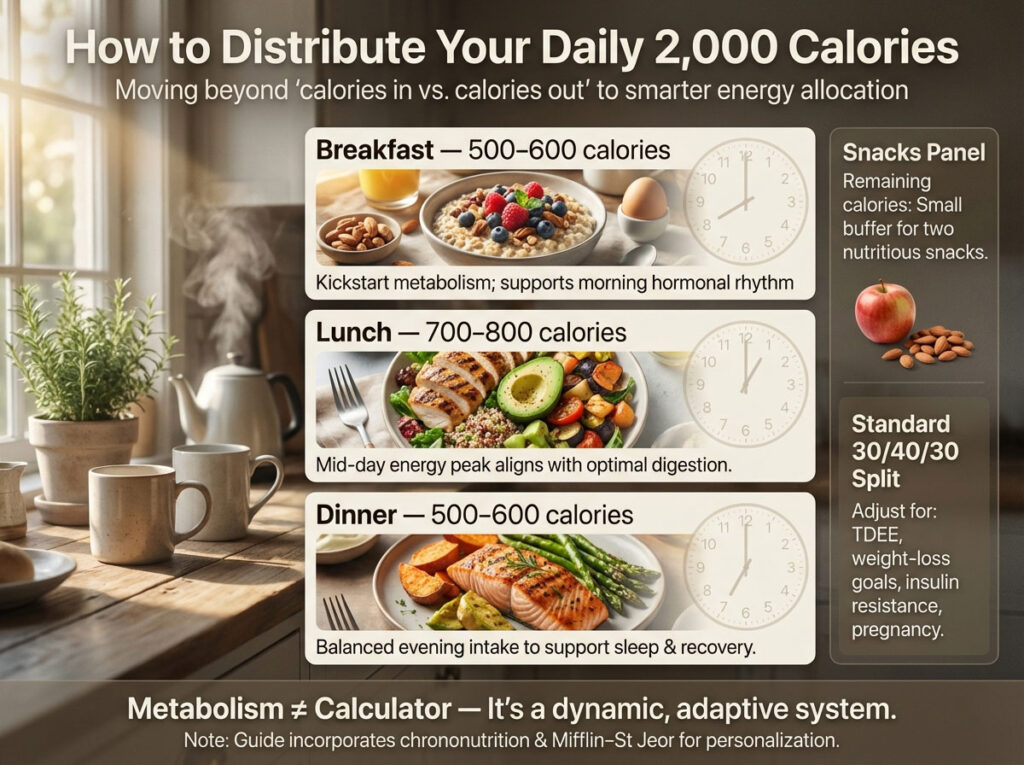

Quick Answer: The Standard Breakdown

For a standard 2,000-calorie diet, a balanced distribution typically follows a 30/40/30 split. This translates to roughly 500–600 calories for breakfast, 700–800 for lunch, and 500–600 for dinner, which leaves a small buffer for two nutritious snacks. However, this is just a baseline. Your specific daily calorie breakdown must be adjusted based on weight loss goals, activity levels (TDEE), and medical variables like insulin resistance or pregnancy.

This comprehensive guide moves beyond generic advice to provide a masterclass in meal planning. We will explore the emerging science of chrononutrition, use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation to find your specific numbers, and provide a precise calories per meal calculator framework that works for your real life.

Calculating Daily Calorie Needs Using the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation

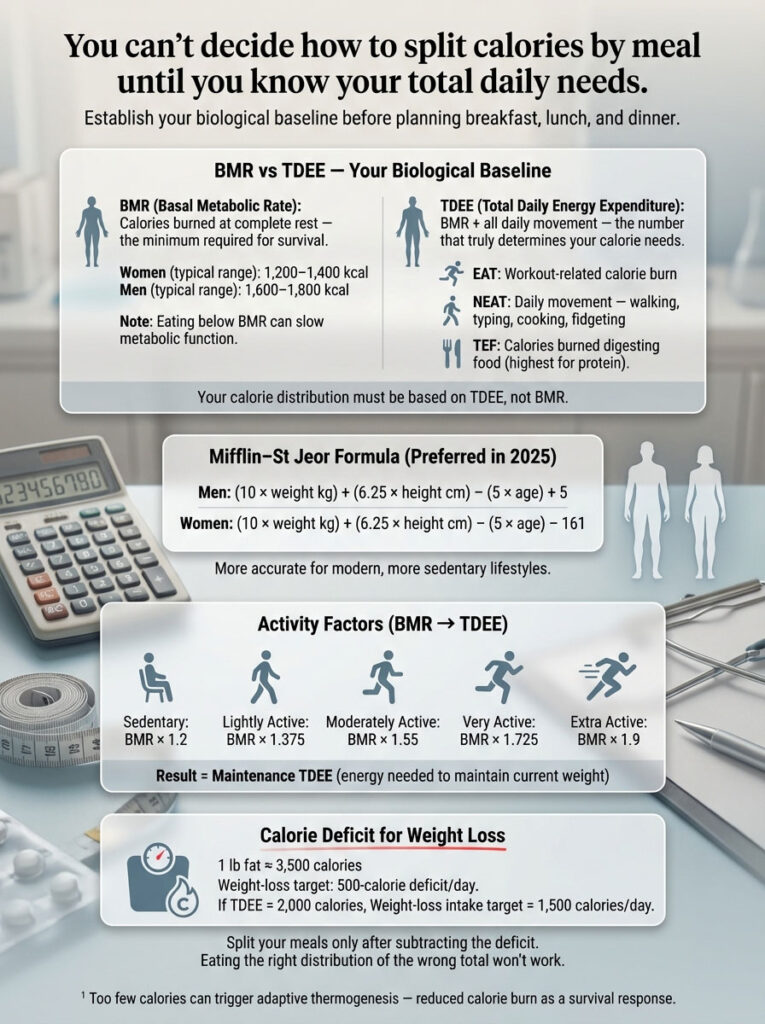

You cannot effectively manage a budget if you do not know your income. Similarly, you cannot decide how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner until you have established your biological baseline. This baseline is not a random guess. It is based on physics and biology. Before we can split the bill, we must know the total.

BMR vs TDEE: Understanding Your Biological Baseline

Most people confuse BMR with TDEE. Understanding the difference is critical for an accurate daily calorie breakdown.

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) is the number of calories your body burns just to keep you alive. If you laid in bed all day in a coma state, your body would still burn energy to pump blood, inflate lungs, fire neurons, and regulate body temperature. For many women, this is around 1,200 to 1,400 calories. For men, it is often 1,600 to 1,800. This is the absolute floor. You should rarely eat below your BMR because doing so signals to your body that food is scarce, potentially slowing down metabolic function over time.

Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) is your BMR plus movement. This is the number you actually need to care about. It is composed of three things beyond your BMR:

- Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT): The calories burned during deliberate workouts like running or lifting weights.

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): This is often the game-changer. NEAT covers the energy used for walking to the car, typing, cooking, fidgeting, and standing. People with high NEAT levels can burn hundreds of extra calories a day without stepping foot in a gym.

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): Your body burns calories just digesting food. Protein has a high TEF, meaning your body works harder to process it than it does fats or carbs.

Your calorie distribution must be based on your TDEE, not your BMR. If you only eat your BMR, you are likely under-fueling, which can lead to muscle loss and fatigue.

Using the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation for Accurate Results

Nutritionists and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics overwhelmingly prefer the Mifflin-St Jeor equation over older methods like the Harris-Benedict equation. The Mifflin-St Jeor formula was developed in 1990 and has proven to be more accurate for modern lifestyles, which tend to be more sedentary than those of the early 20th century.

To create your own calories per meal calculator, start with this formula. You will need your weight in kilograms and height in centimeters.

- Men: (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) – (5 × age in years) + 5

- Women: (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) – (5 × age in years) – 161

Once you have this raw number (your BMR), you multiply it by an activity factor to find your maintenance TDEE:

- Sedentary (Little to no exercise): BMR × 1.2

- Lightly Active (Light exercise 1–3 days/week): BMR × 1.375

- Moderately Active (Moderate exercise 3–5 days/week): BMR × 1.55

- Very Active (Hard exercise 6–7 days/week): BMR × 1.725

- Extra Active (Very hard exercise & physical job): BMR × 1.9

This final number is your maintenance TDEE. This is the amount of energy required to stay exactly the same weight you are today.

How to Calculate a Calorie Deficit for Weight Loss

If your goal is fat loss, the math changes slightly. To lose one pound of fat per week, you generally need a deficit of 3,500 calories per week. This breaks down to a daily deficit of 500 calories.

When asking how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner, you must subtract that 500 from your TDEE first.

- Example: If your calculated TDEE is 2,000 calories.

- The Goal: Your weight loss target becomes 1,500 calories.

- The Split: You now have 1,500 “dollars” to spend across your three meals and snacks.

If you skip this calculation step, any weight loss meal plan split you find online is just a guess. Eating the right distribution of the wrong total will not get you to your goals. Conversely, eating too few calories can trigger adaptive thermogenesis, where your body lowers its calorie burn to protect survival reserves.

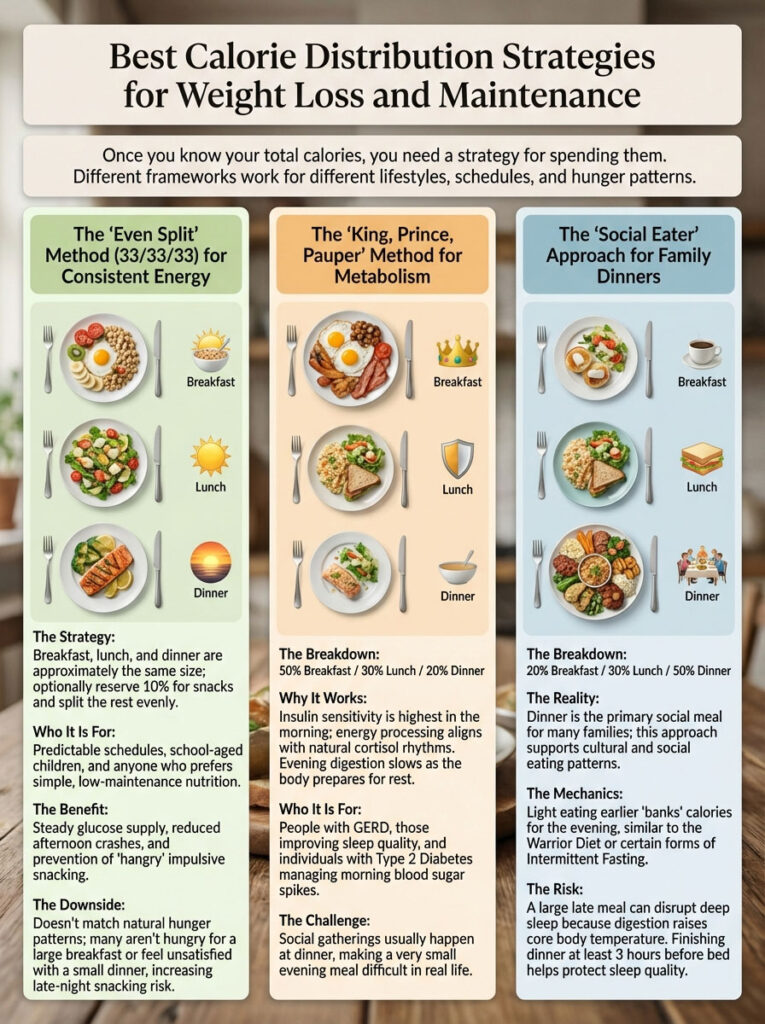

Best Calorie Distribution Strategies for Weight Loss and Maintenance

Once you have your total number, you need a strategy for spending it. There is no single “correct” way to eat. There are different strategies that suit different lifestyles, work schedules, and hunger patterns. We will examine the three most proven frameworks depending on your lifestyle and metabolic health.

The “Even Split” Method (33/33/33) for Consistent Energy

This is the most common calorie distribution method recommended by government health bodies like the USDA and the CDC. You simply take your total TDEE and divide it by three, or perhaps reserve 10% for snacks and divide the rest evenly.

- The Strategy: Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are all approximately the same size.

- Who it is for: This is ideal for people with predictable schedules, school-aged children, and those who do not want to overthink their nutrition. It works well for those who have access to food at regular intervals.

- The Benefit: It provides a steady stream of glucose to the brain and muscles. You avoid the mid-afternoon “crash” because your lunch was substantial enough to carry you through. It also prevents the “hangry” feeling that leads to impulsive snacking.

- The Downside: It does not account for natural fluctuations in hunger. Many people are simply not hungry for a large breakfast but force themselves to eat it to hit the 33% mark. Others find a small dinner unsatisfying and end up snacking late at night, pushing them into a calorie surplus.

The “King, Prince, Pauper” Method for Metabolism

There is an old saying: “Eat breakfast like a King, lunch like a Prince, and dinner like a Pauper.” Modern science, specifically the field of chrononutrition, supports this wisdom.

- The Breakdown: 50% of calories at Breakfast / 30% at Lunch / 20% at Dinner.

- Why it works: Your insulin sensitivity is generally highest in the morning. Your body is primed to process carbohydrates and utilize energy early in the day when cortisol levels are naturally higher. As the sun sets, your body prepares for rest, not digestion.

- Who it is for: This weight loss meal plan split is excellent for people with acid reflux (GERD) who need an empty stomach before bed. It is also beneficial for those struggling with sleep quality or anyone with Type 2 Diabetes looking to manage morning blood sugar spikes.

- The Challenge: It requires a significant lifestyle shift. Most social gatherings happen at dinner, making it difficult to stick to a “pauper” sized meal when dining out with friends.

The “Social Eater” Approach for Family Dinners

This approach flips the “King/Prince/Pauper” model. It reserves the bulk of the daily calorie breakdown for the evening.

- The Breakdown: 20% Breakfast / 30% Lunch / 50% Dinner.

- The Reality: For many American families, dinner is the only time everyone sits together. It is socially difficult to eat a 300-calorie salad while your family eats a roast dinner. This method acknowledges the cultural importance of sharing a meal.

- The Mechanics: By eating lighter during the day, you “bank” calories for the evening. This is similar to the “Warrior Diet” or certain forms of Intermittent Fasting.

- The Risk: While this helps with social adherence, eating a massive meal right before bed can interfere with deep sleep. Digestion raises your core body temperature, but you need your temperature to drop to enter deep REM sleep. If you choose this route, try to finish eating at least 3 hours before sleep to mitigate the negative effects on sleep hygiene.

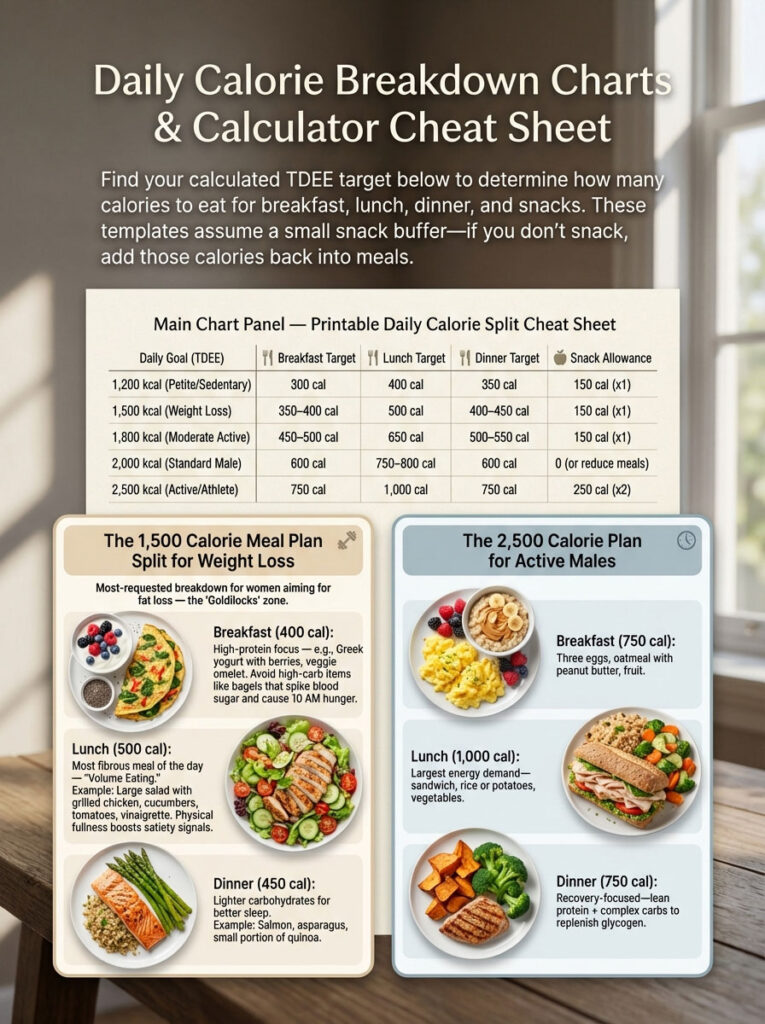

Daily Calorie Breakdown Charts and Calculator Cheat Sheet

To make this actionable, we have created a “cheat sheet.” Find your calculated TDEE target below to see exactly how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner.

These numbers assume you are leaving a small buffer for 1-2 snacks. If you do not snack, simply add those calories back into your main meals. Note that these are templates to help you visualize the volume of food required.

Printable Daily Calorie Split Cheat Sheet

| Daily Goal (TDEE) | Breakfast Target | Lunch Target | Dinner Target | Snack Allowance |

| 1,200 kcal (Petite/Sedentary) | 300 cal | 400 cal | 350 cal | 150 cal (x1) |

| 1,500 kcal (Weight Loss) | 350 – 400 cal | 500 cal | 400 – 450 cal | 150 cal (x1) |

| 1,800 kcal (Moderate Active) | 450 – 500 cal | 650 cal | 500 – 550 cal | 150 cal (x1) |

| 2,000 kcal (Standard Male) | 600 cal | 750 – 800 cal | 600 cal | 0 (or reduce meals) |

| 2,500 kcal (Active/Athlete) | 750 cal | 1,000 cal | 750 cal | 250 cal (x2) |

The 1,500 Calorie Meal Plan Split for Weight Loss

This is the most requested daily calorie breakdown for women aiming for weight loss. It sits in the “Goldilocks” zone—low enough to produce fat loss for most women, but high enough to ensure nutrient sufficiency.

- Breakfast (400 cal): Focus on protein. High protein low calorie meals like Greek yogurt with berries or a veggie omelet keep satiety high. A common mistake here is spending 400 calories on a bagel and cream cheese, which spikes blood sugar and leads to hunger by 10 AM.

- Lunch (500 cal): This should be your most fibrous meal. Think “Volume Eating.” A massive salad with grilled chicken, cucumbers, tomatoes, and a vinaigrette provides physical fullness without blowing the budget. The physical stretching of the stomach wall sends satiety signals to the brain.

- Dinner (450 cal): Keep carbohydrates lighter here. A piece of salmon with asparagus and a small portion of quinoa is perfect. It is substantial enough to feel like a real meal but light enough to allow for restful sleep.

The 2,500 Calorie Plan for Active Males

For men who are physically active or have labor-intensive jobs, the 1,500 calorie model would be starvation. Their breakdown looks drastically different.

- Breakfast (750 cal): This might look like three eggs, oatmeal with peanut butter, and fruit.

- Lunch (1,000 cal): This is often the largest meal to fuel the afternoon’s labor. A large sandwich, a side of rice or potatoes, and vegetables are common.

- Dinner (750 cal): Recovery mode. Lean proteins and complex carbs to replenish glycogen stores in the muscles.

Adjusting Calories for Pregnancy, Diabetes, and Medical Needs

The Mifflin-St Jeor equation gives us a baseline, but biology throws curveballs. You cannot use a standard calories per meal calculator if you are pregnant, breastfeeding, or managing insulin resistance without making adjustments. These are physiological states that fundamentally alter how the body processes energy.

Calories for Breastfeeding vs Pregnancy (Trimesters 1-3)

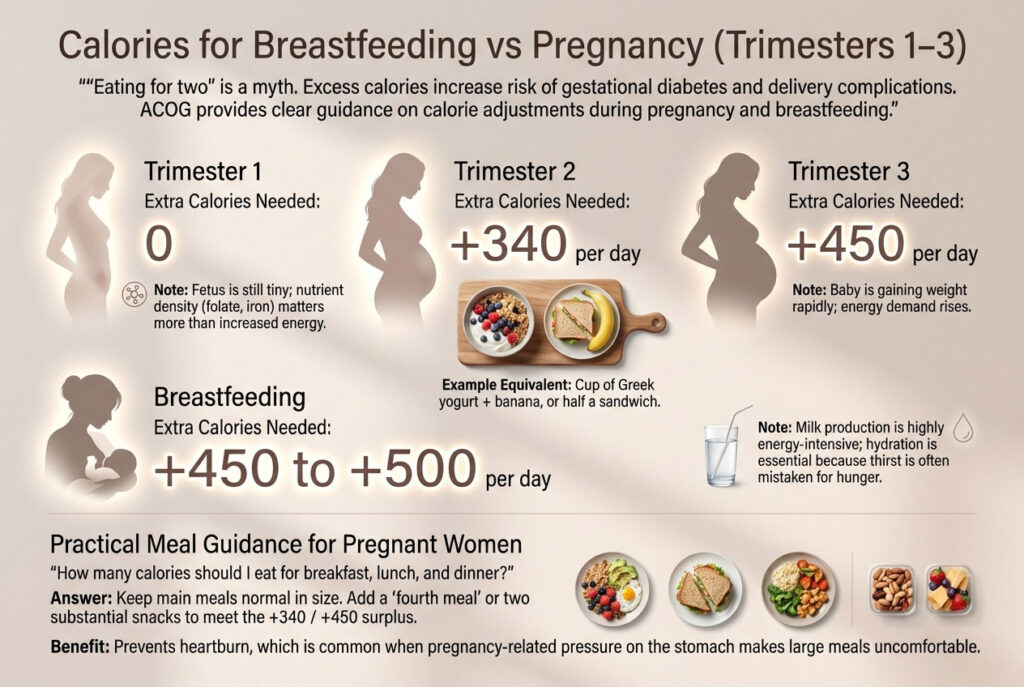

Many women are told they are “eating for two.” This is a well-meaning myth that often leads to excessive weight gain during pregnancy, which can increase the risk of gestational diabetes and complications during delivery. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) provides specific data on calories for breastfeeding vs pregnancy.

- Trimester 1: You generally need 0 extra calories. Your fetus is the size of a lime, and energy demands have not spiked yet. The focus should be on nutrient density (folate, iron) rather than extra energy.

- Trimester 2: You need approximately +340 calories per day. This is not a whole extra meal; it is roughly a cup of Greek yogurt and a banana, or half a sandwich.

- Trimester 3: You need approximately +450 calories per day. The baby is gaining weight rapidly now.

- Breastfeeding: Producing milk is incredibly energy-intensive. You need +450 to 500 calories daily. Hydration is also critical here; often thirst is mistaken for hunger.

For a pregnant woman asking how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner, the answer is to keep your main meal sizes normal but add a “fourth meal” or two substantial snacks to hit that +340/+450 surplus. This helps prevent heartburn, which is very common when eating large meals during pregnancy due to the physical pressure on the stomach.

Meal Planning for Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Resistance

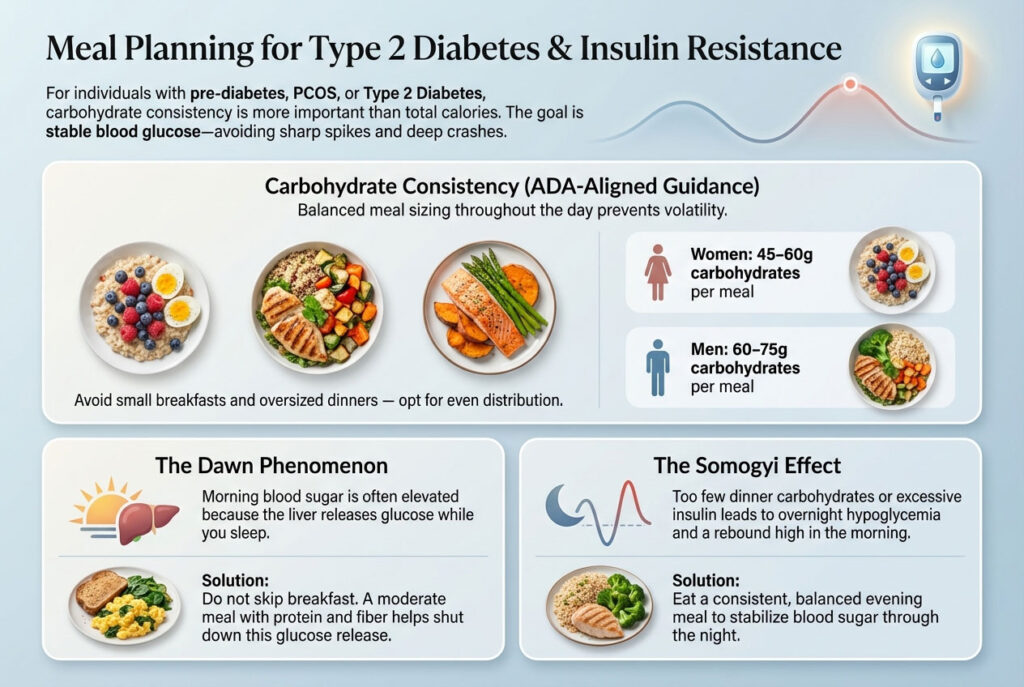

For millions of Americans with pre-diabetes, PCOS, or Type 2 Diabetes, the total calorie count matters less than the carbohydrate consistency. The goal is to keep blood glucose levels in a tight range, avoiding the jagged peaks and valleys that damage blood vessels over time.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends a steady intake of carbohydrates to prevent blood sugar volatility.

- The Strategy: Instead of a tiny breakfast and a huge dinner, you need a balanced calorie distribution.

- The Target: Aim for 45–60g of carbohydrates per meal for women and 60–75g for men.

- The “Dawn Phenomenon”: Many diabetics experience high blood sugar in the morning. Skipping breakfast can worsen this because the liver dumps glucose into the bloodstream to provide energy. A moderate breakfast with protein and fiber shuts down this process.

- The Somogyi Effect: Eating too few carbs at dinner or taking too much insulin can cause a blood sugar crash overnight, leading to a rebound spike in the morning. A consistent evening meal is the defense against this.

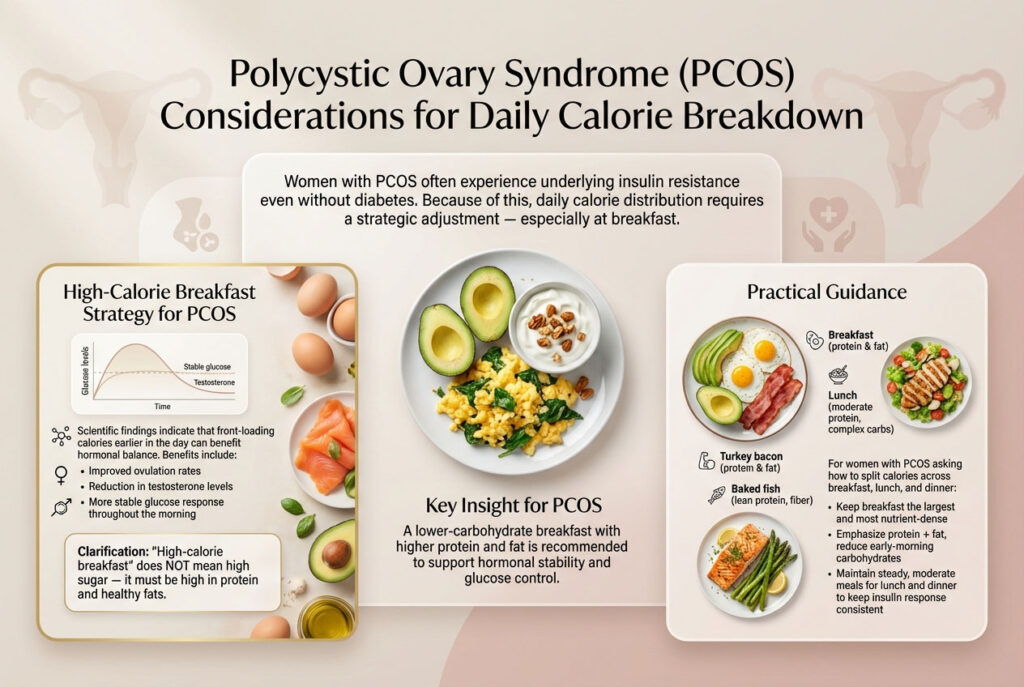

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Considerations

Women with PCOS often have underlying insulin resistance, even if they are not diabetic. For this group, the daily calorie breakdown should prioritize a lower carbohydrate load at breakfast. Studies suggest that a high-calorie breakfast is beneficial for PCOS, but it must be high in protein and fat, not sugar. By front-loading calories, some women with PCOS see improvements in ovulation rates and testosterone reduction.

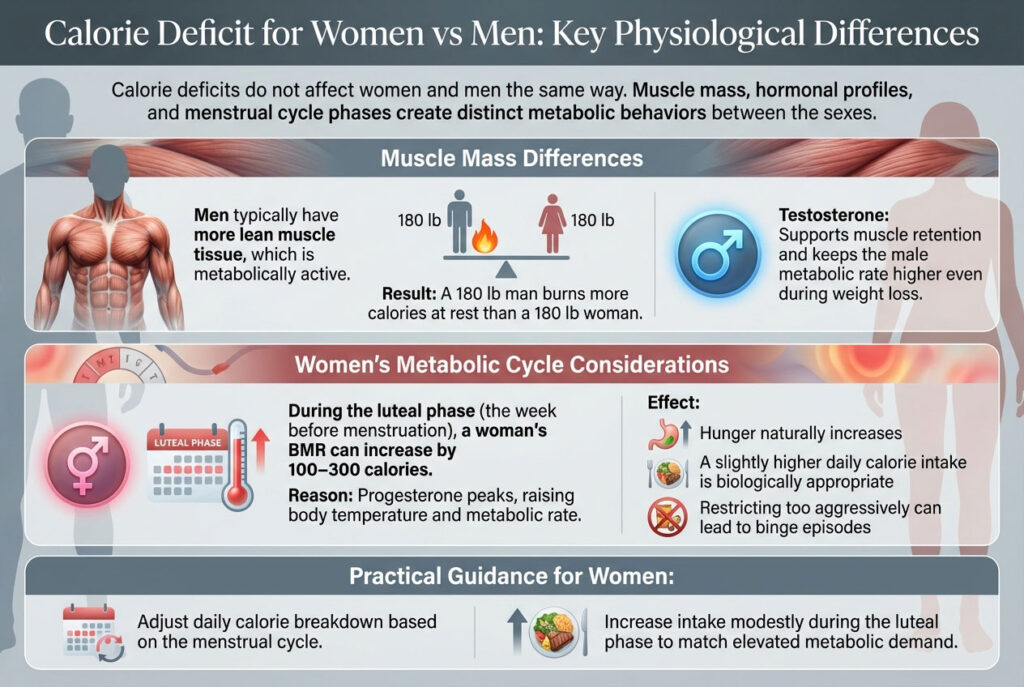

Calorie Deficit for Women vs Men: Physiological Differences

When calculating calorie deficit for women vs men, muscle mass is the primary variable. Men typically have more lean muscle tissue, which is metabolically active. A 180lb man burns more calories sitting in a chair than a 180lb woman because of this tissue difference. Testosterone also promotes muscle retention, keeping the male metabolic rate higher even during weight loss.

Furthermore, women must account for the menstrual cycle. During the luteal phase (the week before menstruation), a woman’s BMR may rise by 100–300 calories. Progesterone levels peak, raising body temperature and metabolic rate. This explains the intense hunger often felt during this week. It is biologically appropriate to slightly increase your daily calorie breakdown during this phase to support the body’s increased energy expenditure. Fighting this hunger too aggressively can lead to binge eating.

Chrononutrition and Meal Timing: Why When You Eat Matters

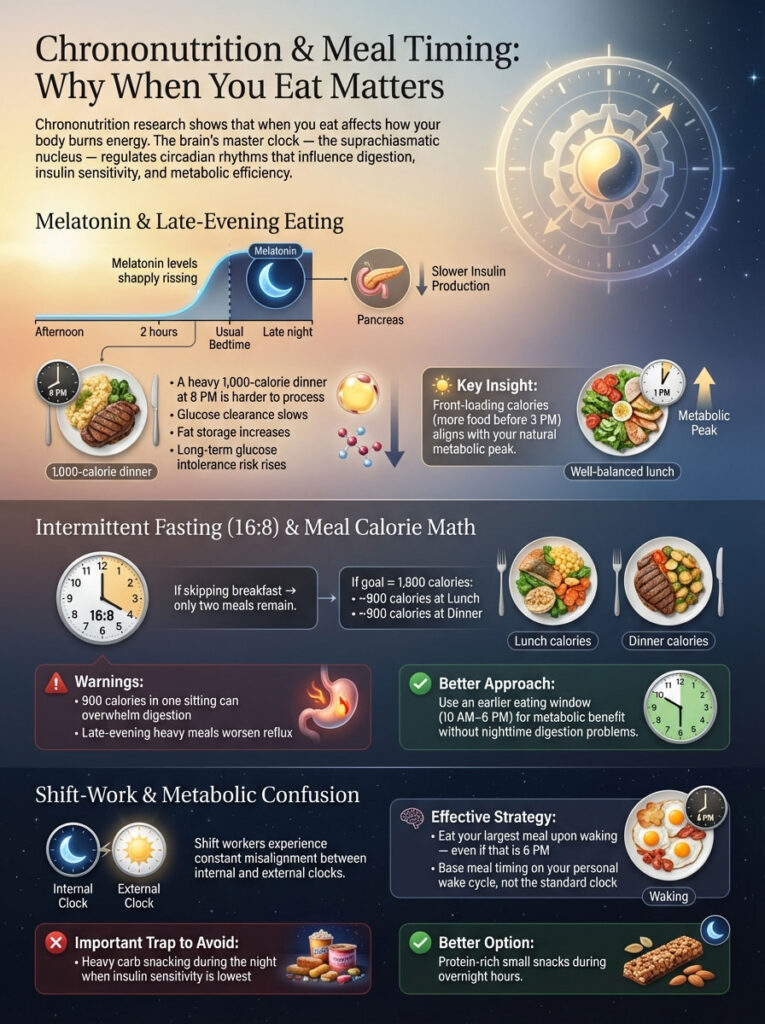

We used to believe that a calorie is a calorie, regardless of when you eat it. Emerging research in the field of chrononutrition challenges this. It turns out that when you eat affects how you burn it. Our bodies have a “master clock” in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which regulates our circadian rhythms.

Melatonin’s Impact on Insulin Sensitivity and Late Eating

Your body runs on a schedule. In the morning, cortisol rises to wake you up and mobilize energy. In the evening, usually two hours before your habitual sleep time, your brain releases melatonin. This hormone tells your body to sleep, but it also communicates with the pancreas.

Melatonin binds to receptors on the pancreas and tells it to slow down insulin production. This makes evolutionary sense; you are not supposed to be hunting and eating while sleeping. However, in the modern world, we often eat our largest meal at 8 PM.

If you eat a heavy 1,000-calorie dinner when melatonin is rising, your body struggles to clear the glucose from your blood because insulin production is suppressed. This can lead to higher fat storage and long-term glucose intolerance. This is why the answer to how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner is shifting toward “Front-Loading.” By moving more of your calorie distribution to the earlier hours (before 3 PM), you align your food intake with your peak metabolic efficiency.

Intermittent Fasting (16:8) and Calorie Intake Per Meal

If you practice Intermittent Fasting (specifically the 16:8 method), you are likely skipping breakfast entirely. This changes your calories per meal calculator math significantly.

If you skip breakfast, you have only two meals (and perhaps a snack) to hit your TDEE.

- The Math: If your goal is 1,800 calories, you now must eat roughly 900 calories at Lunch and 900 at Dinner.

- The Warning: Eating 900 calories in one sitting can be difficult for digestion. It requires strategic food choices to avoid feeling sluggish.

- Reflux Risk: “Back-loading” calories in a short window before bed can exacerbate acid reflux. If you fast, try to shift your eating window earlier (e.g., 10 AM to 6 PM) rather than later (1 PM to 9 PM) to gain the benefits of fasting without the downsides of late-night digestion.

Shift Work Disorder and Metabolic Confusion

For shift workers, the biological clock is constantly at odds with the environmental clock. This group has a higher risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome. If you work nights, your “breakfast” might be at 6 PM.

- The Strategy: The key is to keep the same structure relative to your wake time. Eat your largest meal upon waking (before your shift starts).

- The Trap: Avoid snacking heavily throughout the night shift. The body is still biologically in “night mode” regarding insulin sensitivity. Try to eat protein-rich, small snacks rather than heavy carb meals during the wee hours of the morning.

Visualizing High Volume Low Calorie Meals (Sample Menu)

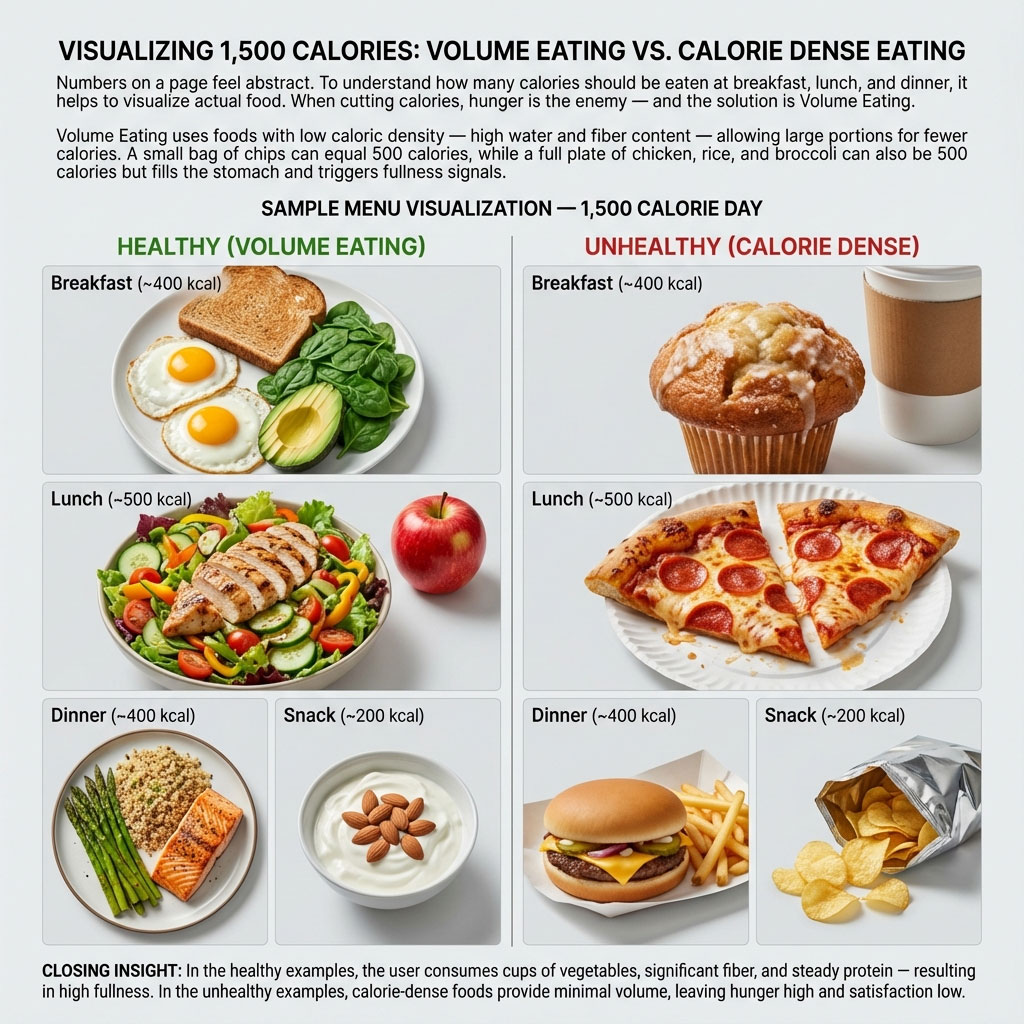

Numbers on a page are abstract. To truly understand how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner, we need to visualize the food. If you are cutting calories, hunger is the enemy. The solution is Volume Eating.

Volume eating focuses on foods with low caloric density. These foods have high water and fiber content, meaning you can eat a large weight of food for very few calories. You can eat 500 calories of potato chips (a small bag) or 500 calories of chicken, rice, and broccoli (a full plate). Both provide the same energy, but the chicken meal fills the stomach physically, triggering stretch receptors that tell the brain, “I am full.”

Sample Menu Visualization for a 1,500 Calorie Day

The table below contrasts a “Volume Eating” day with a “Calorie Dense” day. Both days total approximately 1,500 calories, but the experience of hunger is vastly different.

| Meal | Calorie Target | Healthy Example (Volume Eating) | Unhealthy Example (Calorie Dense) |

| Breakfast | ~400 kcal | 2 Eggs + 1 Slice Whole Wheat Toast + 1/2 Avocado + 1 cup Spinach | Large Coffee Shop Muffin (Often 500+) |

| Lunch | ~500 kcal | Massive Grilled Chicken Salad (Lettuce, cucumber, peppers) + Vinaigrette + Apple | 2 Slices Pepperoni Pizza (Low satiety, high grease) |

| Dinner | ~400 kcal | 4oz Salmon + Asparagus spears + 1/2 cup Quinoa | Fast Food Cheeseburger (Small) |

| Snack | ~200 kcal | Greek Yogurt + 10 Almonds | 1/2 Bag of Potato Chips |

In the healthy example, the user is eating multiple cups of vegetables, getting significant fiber, and sustaining protein intake. In the unhealthy example, the volume of food is tiny, leaving the stomach empty and the user craving more food within an hour.

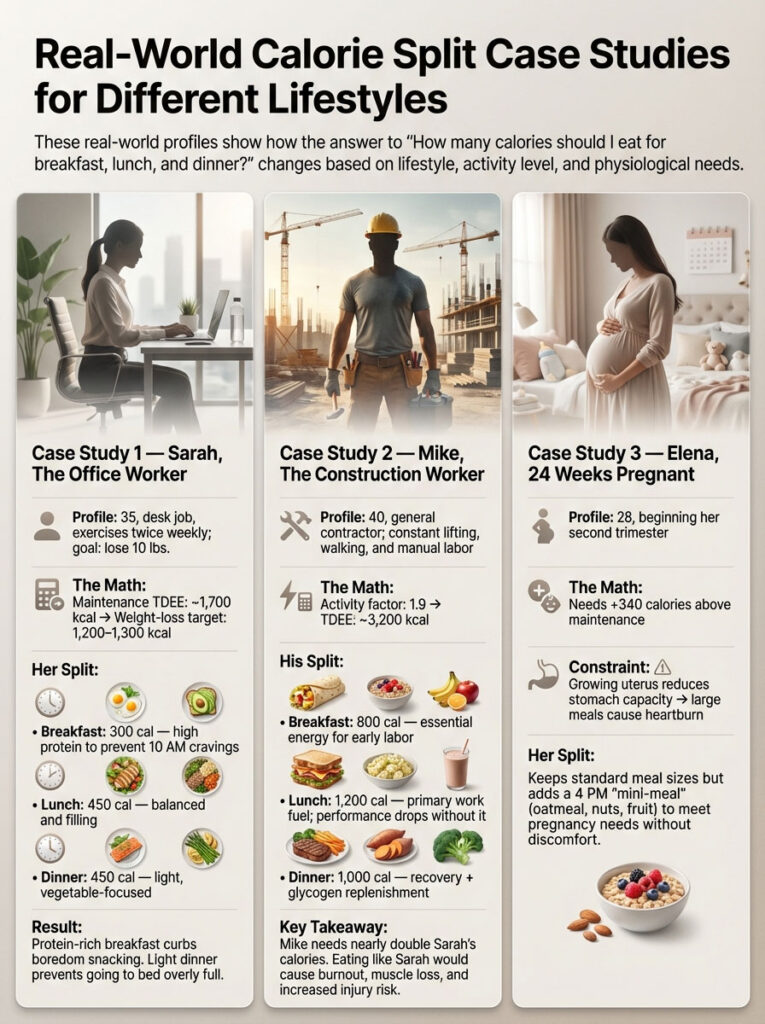

Real-World Calorie Split Case Studies for Different Lifestyles

To put this into perspective, let’s look at three distinct profiles. These case studies illustrate how how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner changes based on lifestyle.

Case Study 1: Sarah, The Office Worker

Profile: Sarah is 35, works a desk job, and exercises twice a week. She wants to lose 10 lbs.

- The Math: Her Mifflin-St Jeor equation puts her maintenance TDEE at 1,700. To lose weight, she targets 1,200–1,300.

- Her Split: Sarah knows she gets bored at her desk and wants to snack. She chooses a High Protein Breakfast (300 cal) to stop the mid-morning hunger. She packs a balanced Lunch (450 cal). She eats a light Dinner (450 cal) focused on vegetables.

- The Result: The protein at breakfast prevents the 10 AM donut craving. By planning a light dinner, she avoids going to bed with a heavy stomach.

Case Study 2: Mike, The Construction Worker

Profile: Mike is 40 and works in general contracting. He is lifting, carrying, and walking all day.

- The Math: Even though he is the same age as a sedentary peer, his activity factor is 1.9. His TDEE is 3,200.

- His Split: He cannot survive on a light lunch. He needs a massive Breakfast (800 cal) to start the day. His Lunch (1,200 cal) is his fuel source; without it, his performance drops. His Dinner (1,000 cal) helps his muscles recover and replenish glycogen for the next day.

- Key Takeaway: Mike’s daily calorie breakdown is nearly double Sarah’s. If he tried to eat like Sarah, he would burn out, lose muscle mass, and likely injure himself.

Case Study 3: Elena, 24 Weeks Pregnant

Profile: Elena is 28 and just entering her second trimester.

- The Math: She needs to add +340 calories to her maintenance.

- The Constraint: Her growing uterus is putting pressure on her stomach, making large meals uncomfortable (causing heartburn).

- Her Split: She keeps her breakfast, lunch, and dinner standard sizes but adds a 4 PM “mini-meal” of oatmeal, nuts, and fruit. This helps her hit her pregnancy nutrient targets without feeling stuffed or suffering from acid reflux at night.

The Role of Macronutrients: It’s Not Just Calories

While this guide focuses on calorie counts, the composition of those calories is equally important. Eating 500 calories of gummy bears for lunch will affect your biology very differently than eating 500 calories of chicken and avocado.

Protein is the most satiating macronutrient. It triggers the release of satiety hormones like peptide YY and GLP-1. If you are struggling to stick to your calorie limits, the first step is often to increase the percentage of protein in your breakfast and lunch.

Fats digest slowly and provide long-term energy, but they are calorically dense (9 calories per gram vs. 4 for protein/carbs). Precise measurement is key here.

Carbohydrates are the body’s preferred fuel source, especially for the brain. However, they cause the sharpest rise in insulin. Pairing carbs with fiber (vegetables) slows this absorption and keeps energy levels stable.

For a balanced meal, aim for a plate that is:

- 1/4 Lean Protein

- 1/4 Complex Carbohydrates (whole grains, starchy veg)

- 1/2 Non-starchy vegetables

- A thumb-sized portion of healthy fats.

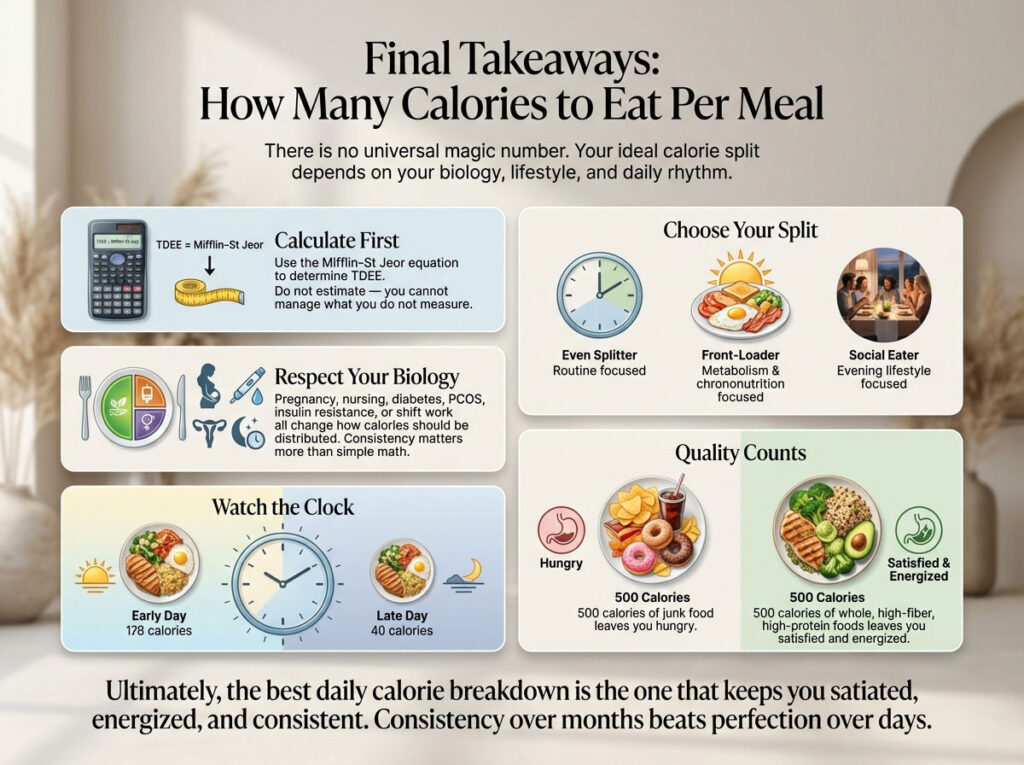

Final Takeaways on How Many Calories to Eat Per Meal

Determining how many calories should I eat for breakfast lunch and dinner is not about finding a magic number that works for everyone. It is about understanding the variables of your own life and respecting your biology.

- Calculate First: Use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation to find your TDEE. Do not guess. You cannot manage what you do not measure.

- Choose Your Split: Decide if you are an “Even Splitter” (routine focused), a “Front-Loader” (metabolism focused), or a “Social Eater” (lifestyle focused).

- Respect Your Biology: If you are pregnant, nursing, diabetic, or shift-working, your rules are different. Consistency matters more than simple calorie math.

- Watch the Clock: Try to eat the majority of your calories before evening to align with chrononutrition principles. Front-loading calories can improve insulin sensitivity and weight management.

- Quality Counts: 500 calories of junk food will leave you hungry. 500 calories of whole foods will leave you fueled.

Ultimately, the best daily calorie breakdown is the one that keeps you satiated, energized, and consistent. Consistency over months beats perfection over days.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How many calories should I eat for breakfast to lose weight?

Research suggests aiming for 300–400 calories for breakfast, specifically high-protein choices. Studies show that a high-protein breakfast (containing over 30g of protein) reduces cravings and snacking later in the day. This “second-meal effect” means that what you eat at 8 AM influences what you choose to eat at 1 PM. Skipping breakfast often backfires, leading to binging later in the day.

Does it matter if I eat all my calories in one meal (OMAD)?

While you can technically lose weight on One Meal A Day (OMAD) if you stay in a calorie deficit, it is not optimal for everyone. Eating 1,500+ calories in one sitting can cause digestive distress, massive insulin spikes, and lethargy. It puts a heavy load on the digestive system. Furthermore, it is very difficult to get all your required micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) in a single meal. It is generally not recommended for those with insulin resistance, gastric issues, or history of disordered eating.

Is skipping dinner good for weight loss?

From a chrononutrition perspective, yes. Skipping dinner (sometimes called “dinner cancelling”) aligns with your circadian rhythm and can improve fat oxidation overnight. It extends the overnight fasting window, allowing the body to enter a state of repair and autophagy. However, it is socially difficult to maintain long-term. If you choose this, ensure your breakfast and lunch are substantial enough to prevent hunger from waking you up at night.

How many calories are in a typical restaurant dinner?

Restaurant meals are notoriously calorie-dense due to hidden butters, oils, and large portion sizes. A typical restaurant dinner entree often contains 1,000 to 1,500 calories, which is nearly an entire day’s allowance for some women. If you are dining out, consider splitting an entree, asking for sauces on the side, or treating the meal as your single large meal for the day (the “Social Eater” strategy).

Do men really need larger portions than women?

Generally, yes. Because men naturally have more lean muscle mass and larger internal organs, their Basal Metabolic Rate is higher. A man and woman of the same height and weight will still have different calorie needs, with the man usually requiring more. However, this gap narrows as we age and men lose muscle mass, or if the woman is highly athletic and the man is sedentary.

How do I split calories if I work night shifts?

If you work nights, your “breakfast” might be at 6 PM. The key is to keep the same structure relative to your wake time: eat your largest meal upon waking (before your shift starts) to fuel your work. Avoid heavy meals 3-4 hours before your sleep time, even if that sleep time is 10 AM. Light exposure and meal timing are the two biggest anchors for your circadian rhythm, so keeping them consistent is vital for metabolic health.

What are “empty calories”?

Empty calories refer to foods that provide energy (calories) but little to no micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, fiber). Common examples include alcohol, soda, sugary candy, and highly processed pastries. When planning your daily calorie breakdown, these should be minimized because they do not provide satiety. They spike blood sugar and leave you hungry shortly after, making it harder to stay within your calorie deficit.

Does breastfeeding really burn extra calories?

Yes. Lactation is metabolically expensive, burning approximately 450–500 calories per day. This is roughly equivalent to running 4-5 miles. This is why nursing mothers often feel extreme, insatiable hunger. It is crucial to increase caloric intake with nutrient-dense foods to support milk production. Severely restricting calories while breastfeeding can reduce milk supply and deplete the mother’s nutrient stores.

Should I eat before or after a workout?

Ideally, both, but the size depends on the timing. A small carb-focused snack (150 cal) 30-60 minutes before a workout provides readily available fuel for your muscles. A protein-rich meal (400+ cal) within 2 hours after the workout aids in muscle recovery and glycogen replenishment. You can shift calories from dinner to these windows to support your training performance and recovery.

Can I “bank” my calories for the weekend?

“Banking” calories (eating very little during the week to binge on the weekend) is a dangerous cycle. It often leads to a binge-restrict relationship with food. It can disrupt hunger hormones and lead to metabolic slowdown during the week. It is better to maintain a consistent daily calorie breakdown and allow for a moderate indulgence (perhaps one meal) without starving yourself beforehand. Consistency is key to sustainable weight management.

How do I track calories accurately?

Studies show humans are terrible at estimating portion sizes; we tend to underestimate what we eat by up to 40%. To be accurate, especially when starting, you need a digital food scale and a tracking app. Eyeballing a tablespoon of peanut butter often results in eating three servings instead of one. Using a scale for a few weeks trains your eye to recognize what a true serving size looks like.

What does 500 calories actually look like?

500 calories can look drastically different depending on the food source. It is equal to:

4 ounces of Grilled Salmon + 1 cup Quinoa + 1 cup Roasted Broccoli.

OR One medium “Venti” Frappuccino with whipped cream.

OR Two regular slices of pepperoni pizza. The salmon meal keeps you full for 4 hours and provides protein, fiber, and omega-3s. The drink keeps you full for 30 minutes and provides only sugar. The pizza provides energy but little satiety. Choosing high-volume, nutrient-dense foods is the secret to feeling full on a calorie budget.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Calorie needs are highly individual and dependent on factors like genetics, medication, and health history. Always consult with a registered dietitian or healthcare provider before making significant changes to your diet, especially if you have conditions like diabetes, eating disorders, or are pregnant.

References

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Nutrition During Pregnancy.

- American Diabetes Association (ADA). Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2024.

- Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “Chrononutrition: The relationship between time of eating and health outcomes.”

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Body Weight Planner.

- Sleep Foundation. “The Connection Between Diet, Exercise, and Sleep.”