You are standing in the grocery aisle. You hold a carton of soy milk in one hand. You feel a sense of hesitation. You have read the forums. You have heard the rumors. You likely have a diagnosis of Hashimoto’s or an underactive thyroid. The conflicting information regarding soy and hypothyroidism is enough to make anyone’s head spin. Some experts hail soy as a heart-healthy plant protein. Others demonize it as a hormone-disrupting toxin that will destroy your gland.

Table of Contents

Here is the truth. The question “Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid” requires a nuanced answer. It is not a simple yes or no. The answer depends on your iodine status. It depends on your medication timing. It depends on the state of your gut microbiome. It depends on the type of soy you are eating.

In this comprehensive guide, we will dismantle the myths. We will look at the biochemistry. We will examine the clinical data. We will provide you with a definitive protocol to navigate the grocery store with confidence.

Quick Answer: Current clinical consensus from the American Thyroid Association indicates that soy and hypothyroidism can coexist safely. This is true provided the patient is iodine-sufficient. While soy isoflavones can theoretically inhibit thyroid enzymes, human studies show they do not significantly alter TSH levels in healthy adults. The primary risk is thyroid medication absorption. Soy protein can bind to levothyroxine. This reduces its effectiveness. Patients should maintain a strict 4-hour window between taking medication and consuming soy products.

Key Statistics & Data Points

- 4 Hours: The minimum time required between taking levothyroxine and consuming soy to prevent absorption issues (ATA Guidelines).

- 150 mcg: The recommended daily allowance (RDA) of iodine for adults to prevent soy from acting as a goitrogen.

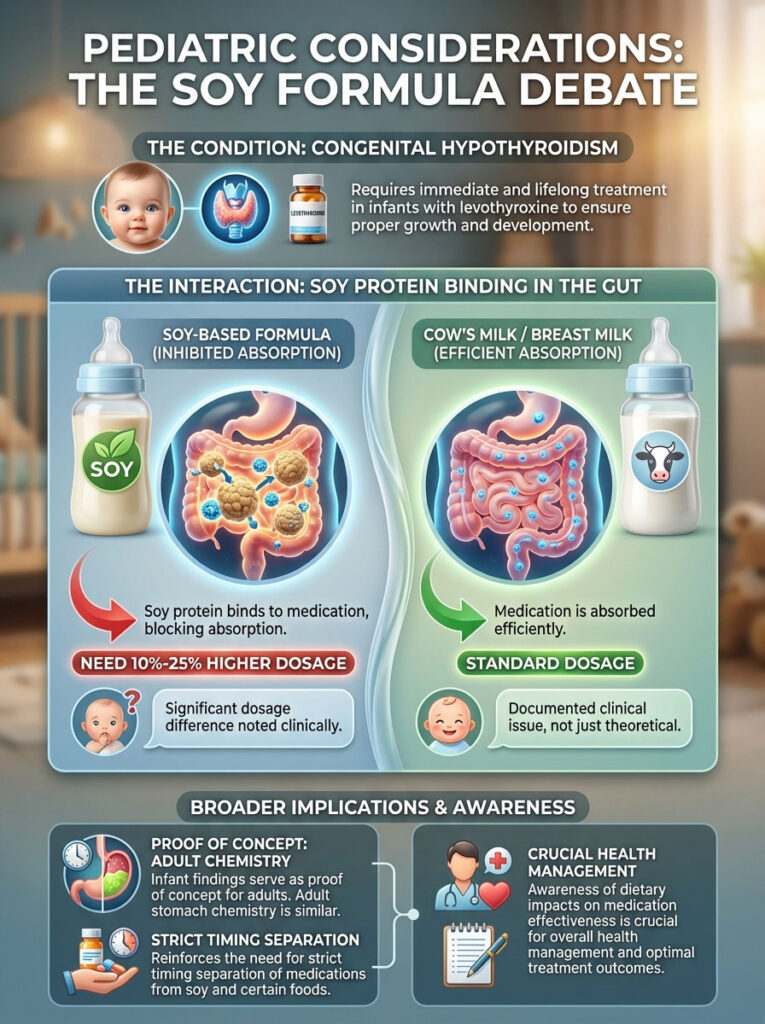

- 25%: Infants on soy formula may require up to a 25% increase in levothyroxine dosage compared to those on milk formula (Journal of Pediatrics).

- 2-3 Servings: The generally accepted safe daily limit of soy foods for thyroid patients. This assumes normal iodine status.

- 0.6-1.6%: The prevalence of overt hypothyroidism in the US population. Many of these patients unnecessarily restrict soy.

The Soy-Thyroid Controversy Decoded

Every week in clinical practice, I hear the same concern from patients. “I have Hashimoto’s. I’ve been told to never touch tofu again.” The frustration is palpable. Frankly, it is justified. The internet is awash with conflicting advice regarding soy and hypothyroidism. This leaves patients paralyzed in the grocery aisle. Some sources claim edamame is a superfood. Others label it a thyroid toxin.

Here is the reality. Soy is not a monolith. The question “Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid” cannot be answered without looking at your specific physiology. The confusion stems from a lack of distinction between two mechanisms. The first is goitrogenic potential. This refers to interfering with hormone production. The second is medication interference. This refers to blocking hormone absorption.

These are two very different problems. They require two very different solutions. Our goal here is to separate outdated animal studies from current human clinical trials. We will understand the biochemistry of isoflavones. We will assess your personal iodine status. We will implement proper medication timing. By doing this, you can likely integrate soy into a thyroid-friendly diet without compromising your endocrine function.

The Biochemistry of Soy: Isoflavones and Thyroid Function

To understand the interaction between soy and hypothyroidism, we must look at the molecular level. Soybeans are legumes. They are rich in phytoestrogens known as isoflavones. The two primary compounds we focus on are Genistein and Daidzein. These compounds are structurally similar to mammalian estrogen. This is why they are often discussed in the context of women’s health and menopause.

However, the thyroid sees them differently. In the context of the thyroid, Genistein acts as a “suicide substrate” in test-tube (in vitro) studies. It essentially distracts an enzyme called Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO).

The Role of Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO)

TPO is the worker bee of your thyroid gland. Its job is crucial. It attaches iodine molecules to a protein called tyrosine. This process creates T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine). Without TPO, you cannot make thyroid hormones. This leads to hypothyroidism.

When TPO is inhibited in a test tube by Genistein, thyroid hormone production drops. This sounds alarming. It sounds like proof that soy is dangerous. But here is the catch. The human body is not a test tube. In vivo (in the body) studies show a different picture.

The Human Difference

Research published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism has demonstrated a vital fact. In humans with adequate iodine intake, this TPO inhibition is negligible. The body is resilient. It has compensatory mechanisms. These mechanisms prevent isoflavones from crashing your thyroid function. This is true provided you have the raw materials needed to make the hormone.

The liver plays a massive role here. When you eat soy, your liver processes these isoflavones rapidly. They are conjugated and excreted. This means the actual concentration of “active” free genistein that reaches the thyroid gland is very low. It is often too low to cause the damage seen in test tubes.

Expert Insight: Do not rely on studies done on rats. Rodents metabolize soy isoflavones much more efficiently than humans. This leads to much higher circulating levels in their blood. Human clinical trials consistently show that soy and hypothyroidism are not causally linked in iodine-sufficient populations.

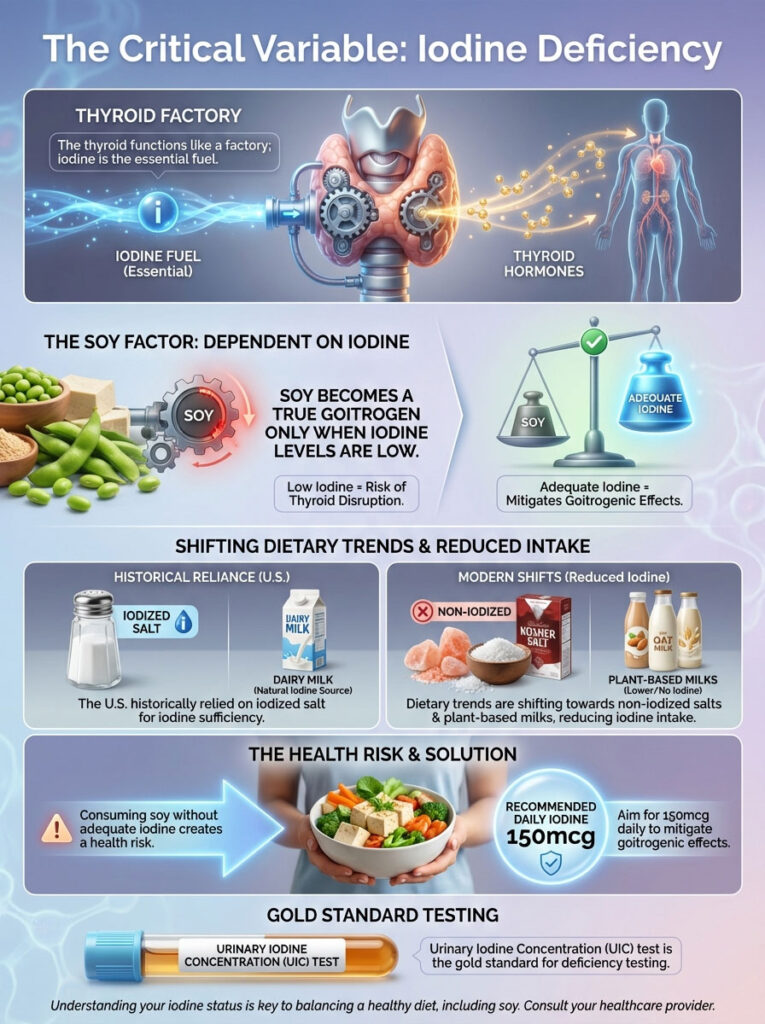

The Critical Variable: Iodine Deficiency

The relationship between soy and the thyroid is synergistic. It is not a one-way street. Soy is only a true goitrogen when iodine is scarce. A goitrogen is a substance that causes a goiter. A goiter is an enlargement of the gland. Think of soy as a “second hit” to the system.

Imagine your thyroid is a factory. Iodine is the fuel. If the factory is fully fueled, a minor distraction (like soy) does not stop production. But if the factory is running on fumes, that distraction becomes catastrophic.

The Iodine Crisis in Modern Diets

If your thyroid is already starving for iodine, the addition of genistein makes it harder for the gland to capture what little iodine is available. In the United States, we have historically considered ourselves iodine-sufficient. This is due to the introduction of iodized salt in the 1920s. However, dietary trends are shifting.

Many health-conscious individuals are the same people asking “Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid“. These individuals have switched their salt habits. They use sea salt. They use Himalayan pink salt. They use Kosher salt. None of these typically contain added iodine.

Additionally, the rise of plant-based milks means less iodine from dairy products. Dairy is a primary source of iodine in the western diet. If you are consuming significant amounts of soy while avoiding iodized salt and dairy, you are creating a perfect storm. You may be inadvertently creating the environment where soy becomes problematic. For the average patient, ensuring an intake of 150mcg of iodine per day neutralizes the goitrogenic risk of moderate soy consumption.

Testing Your Status

How do you know if you are deficient? A simple urine test can tell you. The Urinary Iodine Concentration (UIC) test is the gold standard. If you are consuming soy and feel fatigue, do not just blame the tofu. Check your iodine first.

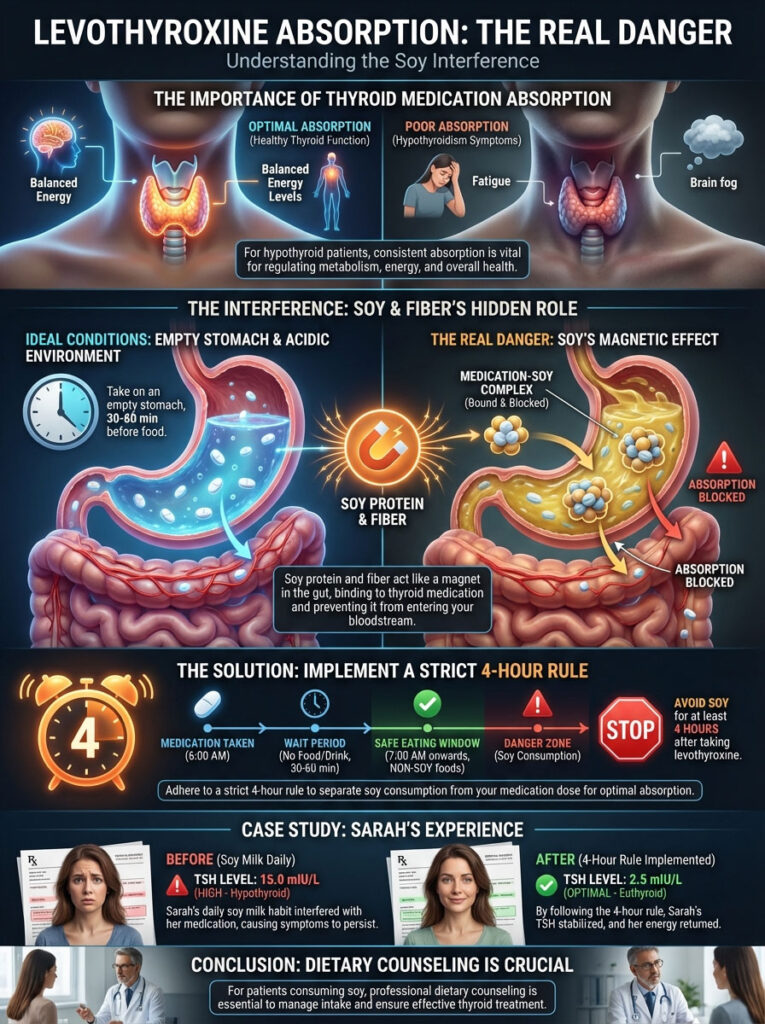

Levothyroxine Absorption: The Real Danger

We have established that soy likely will not damage the gland itself if you have iodine. But there is a bigger problem. The risk of soy interfering with thyroid medication absorption is very real. It is clinically significant. This is the area where patients must exercise the most caution.

Synthetic thyroid hormones like levothyroxine (Synthroid, Tirosint, Levoxyl) are notoriously finicky. They are delicate molecules. They require a highly acidic gut environment for optimal absorption. They need an empty stomach. They need no competition.

The Binding Effect

Soy protein and soy fiber have a high affinity for binding to these medications in the gastrointestinal tract. Imagine the soy protein as a magnet. Imagine the thyroid medication as metal filings. When they meet in the stomach, the magnet traps the metal.

When the soy protein binds to the thyroxine molecule, it prevents it from entering the bloodstream. The medication cannot get to your cells. Instead, the medication travels through the intestines. It is eventually excreted in the stool. You effectively flushed your medication down the toilet.

The 4-Hour Rule

To navigate this, we implement a strict timing protocol. If you take your medication at 7:00 AM, you should not consume soy products until 11:00 AM. This allows the medication to be fully absorbed into the system. It usually takes about 60 to 120 minutes for the bulk of the medication to leave the stomach. We add a buffer to be safe.

Consider the case of a patient we will call “Sarah.” Sarah had stable TSH levels for years. Her TSH was a perfect 1.5. Suddenly, her TSH spiked to 6.5. This indicates hypothyroidism. She felt tired. She gained weight. Yet, her dose had not changed.

Upon review, we discovered a change in her routine. She had started adding soy milk to her morning coffee. She drank this coffee 30 minutes after her pill. The soy was binding the medication. It was effectively lowering her dose. We made one change. She switched to almond milk for the morning coffee. She saved the soy for lunch. Her TSH normalized within six weeks. No dosage change was needed.

This interaction is why thyroid medication absorption is the central focus of dietary counseling for hypothyroid patients consuming soy.

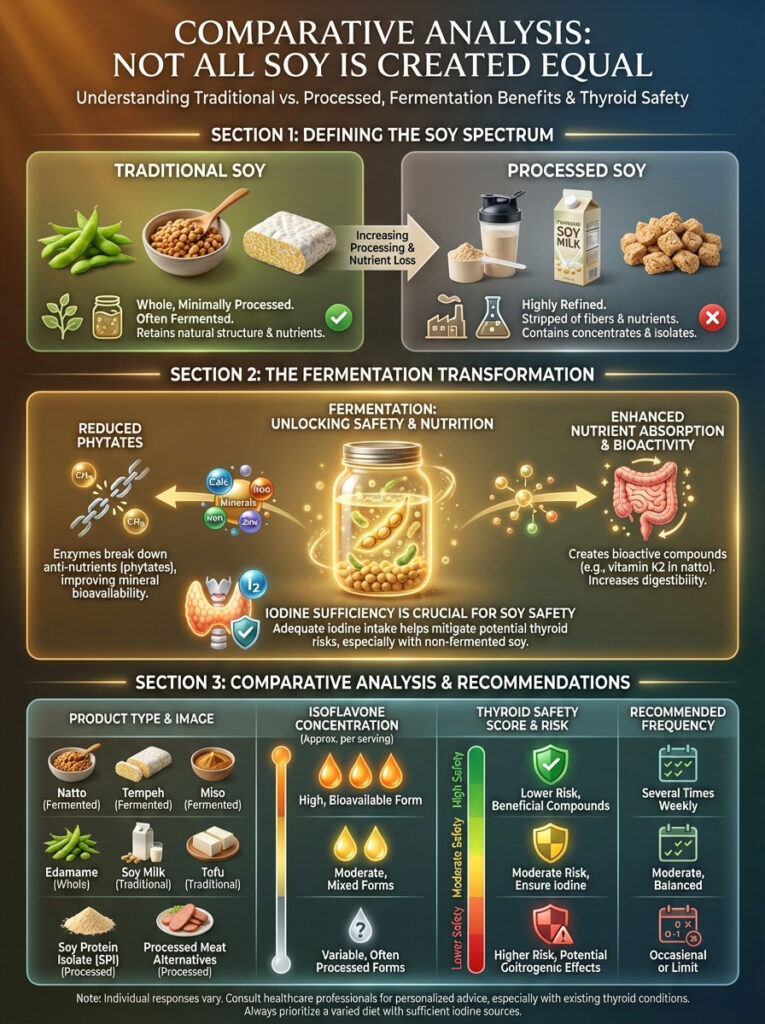

Comparative Analysis: Not All Soy is Created Equal

When answering “Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid,” we must define what kind of tofu or soy we are discussing. The soybean is versatile. The processing of the soybean dramatically changes its chemical profile. It changes how it interacts with the body.

There is a massive difference between a block of traditional miso and a processed protein bar. We must categorize them to understand the risk.

The Magic of Fermentation

Fermentation is a traditional method used in Asian cultures. It significantly improves the safety profile of soy. The fermentation process is used to make Tempeh, Miso, and Natto. Bacteria or fungi are introduced to the beans. They break down the beans over time.

This process breaks down phytates. Phytates are anti-nutrients that block mineral absorption. Fermentation also “pre-digests” some of the proteins. This makes the nutrients more bioavailable. It makes the food less likely to trigger gut inflammation. This is vital for patients with autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto’s.

The Danger of Isolates

Conversely, Soy Protein Isolate (SPI) is a different beast. It is a highly processed powder. It is found in protein bars. It is found in veggie burgers. It is found in meal replacements. To make SPI, the soybean is bathed in chemicals to strip away fiber and fat.

SPI contains high concentrations of isoflavones. It lacks the food matrix that usually accompanies them. This concentrated form is more likely to cause issues with thyroid medication absorption. It is also more likely to cause gut irritation than whole food sources.

| Soy Product Type | Isoflavone Concentration | Fermentation Status | Thyroid Safety Score (1-10) | Recommended Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tempeh | High | Yes | 9/10 | 2-3x Weekly |

| Miso Paste | Moderate | Yes | 9/10 | Daily (moderate) |

| Natto | High | Yes | 8/10 | 1-2x Weekly |

| Edamame (Whole) | Moderate | No | 7/10 | 1-2x Weekly |

| Tofu (Calcium Set) | Moderate | No | 7/10 | 1-2x Weekly |

| Soy Milk | Variable | No | 5/10 | Caution with Meds |

| Soy Protein Isolate | Very High | No | 3/10 | Avoid/Limit |

Note: Safety scores reflect potential for medication interference and digestibility. This assumes iodine sufficiency.

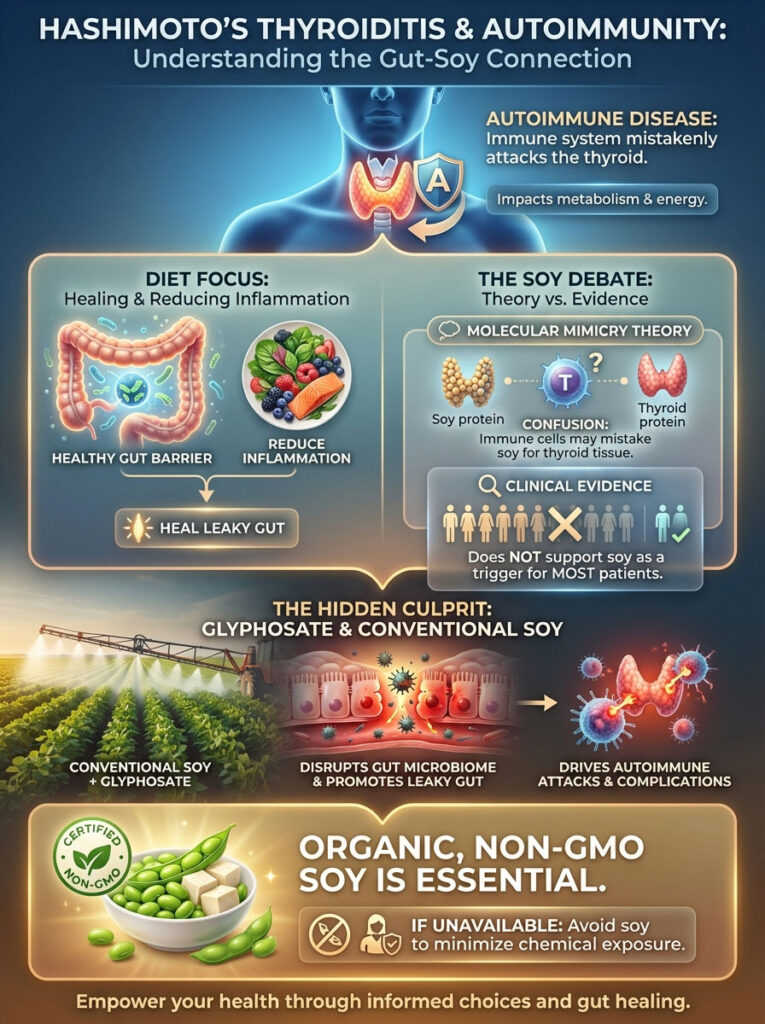

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Autoimmunity

For patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, the concern often shifts. We stop worrying about goiters. We start worrying about the immune system. Hashimoto’s is an autoimmune disease. The Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis diet focuses on reducing inflammation. It focuses on healing intestinal permeability. This is often called “Leaky Gut.”

The Molecular Mimicry Theory

There is a persistent theory in the functional medicine world. It suggests that soy protein mimics the structure of thyroid tissue. This is called molecular mimicry. The theory posits that when you eat soy, the immune system gets confused. It attacks the soy protein. But because the thyroid looks similar, it attacks the thyroid too.

While this is a compelling theory, clinical evidence supporting it is sparse. We do not see this happen in the majority of patients. For the vast majority of Hashimoto’s patients, soy does not trigger an antibody spike. TPO antibodies usually remain stable with moderate soy intake.

The Real Culprit: Glyphosate

However, quality matters immensely here. We cannot ignore farming practices. Conventional soy crops in the USA are heavily treated with glyphosate. This is the active ingredient in Roundup. Glyphosate is a desiccant and an herbicide.

Glyphosate has been shown to disrupt the gut microbiome. It kills beneficial bacteria. It potentially damages the tight junctions of the intestinal lining. This leads to leaky gut. Leaky gut drives autoimmune attacks.

When a patient reports feeling “inflamed” after eating soy, we must ask a question. Is it the soy? Or is it the chemical residue? Often, it is the chemicals. Therefore, organic, non-GMO soy is non-negotiable for the Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis diet. If you cannot find organic tofu, it is better to skip it.

Pediatric Considerations: The Soy Formula Debate

The most compelling evidence we have regarding thyroid medication absorption comes from pediatric endocrinology. We look to the babies for proof. Congenital hypothyroidism is a condition where infants are born with an underactive thyroid. Treatment is immediate. It is lifelong.

Studies have consistently shown a stark contrast. Infants fed soy-based formula require 10% to 25% higher doses of levothyroxine. This is compared to infants fed cow’s milk formula or breast milk. The soy protein in the formula binds the medication in the infant’s gut. It prevents uptake.

Why This Matters for Adults

Why does this matter for you, an adult? It serves as a proof of concept. It validates the biochemistry. If soy formula can block medication absorption in an infant to the point where dosage changes are required, a soy protein shake can certainly do the same to an adult.

Adults have larger stomachs. But the chemistry is identical. This validates the need for strict timing separation. It is not just a theoretical risk. It is a documented clinical phenomenon.

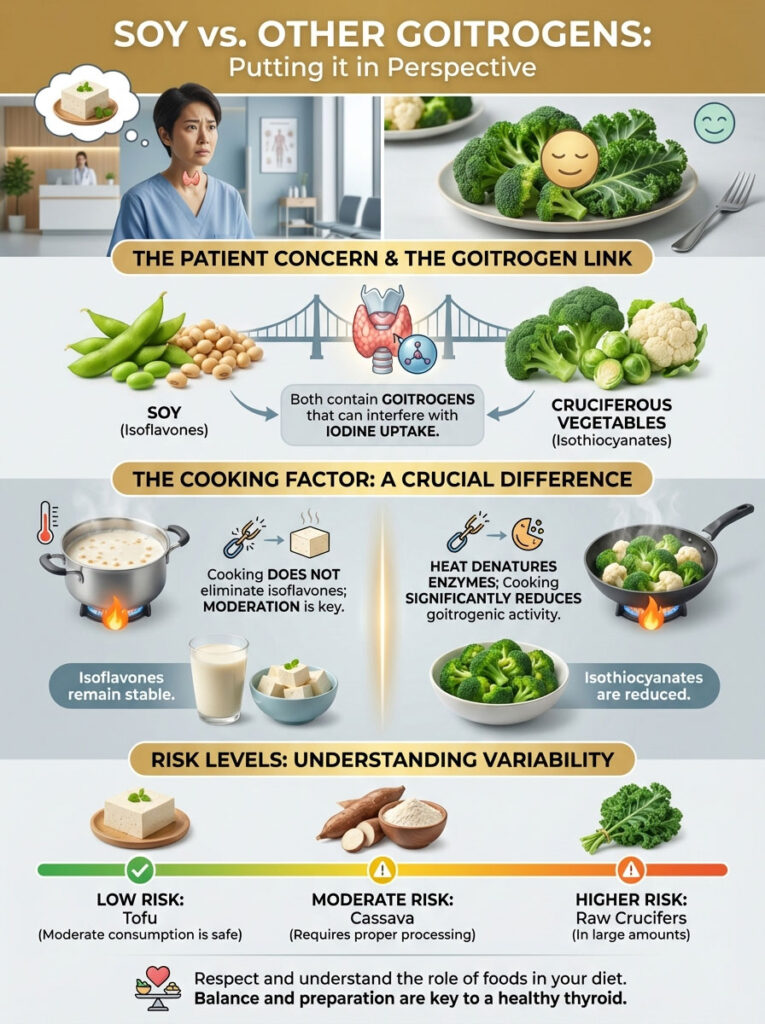

Soy vs. Other Goitrogens: Putting it in Perspective

It is fascinating to observe patient behavior. Patients will ask “Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid” with great concern. Yet, they will happily consume kale smoothies daily. They will eat cauliflower rice. They will snack on broccoli.

Here is the irony. Both soy and cruciferous vegetables contain goitrogens. In crucifers like kale, broccoli, and cauliflower, the compounds are called isothiocyanates. They work similarly to isoflavones. They can interfere with iodine uptake.

The Impact of Cooking

The key difference lies in preparation. Cooking cruciferous vegetables significantly lowers their goitrogenic activity. Heat denatures the enzymes responsible for activating these compounds. If you boil broccoli, the goitrogens are largely deactivated.

With soy, cooking helps. But isoflavones are more heat-stable than the goitrogens in broccoli. Boiling tofu does not remove the isoflavones. However, this does not mean soy is dangerous. It simply means moderation is required. It means we must respect the food.

| Food Item | Primary Goitrogen | Effect of Cooking | Risk Level (Iodine Sufficient) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soy (Tofu/Milk) | Isoflavones | Minimal Reduction | Low |

| Kale/Broccoli | Isothiocyanates | Significant Reduction | Very Low |

| Cassava | Thiocyanates | Moderate Reduction | Moderate |

| Sweet Potato | Cyanogenic Glycosides | Significant Reduction | Very Low |

The Menopause Intersection: Estrogen and Thyroid

Many women dealing with hypothyroidism are also navigating perimenopause or menopause. This is a common overlap. Soy is often recommended for menopausal symptoms. The phytoestrogens can help mitigate hot flashes. They can support bone density.

But does this benefit come at a cost to the thyroid? Generally, no. Dietary soy can be a helpful tool here. The estrogenic effect is weak. It is about 1/1000th the strength of human estrogen. This is often enough to soothe a hot flash. It is rarely enough to disrupt thyroid feedback loops.

The Supplement Danger

However, there is a major caveat. We must distinguish between tofu and “Isoflavone Supplements.” You see these in the pharmacy. They are marketed for menopause relief. These pills contain concentrated doses of genistein. They far exceed what you would get from a block of tofu.

These supplements can pose a higher risk. They create a massive spike in blood isoflavone levels. This can theoretically stress the thyroid. It can also interfere with medication more aggressively. If you are hypothyroid, avoid concentrated soy pills. Stick to the whole food.

Hidden Sources: Soy Lecithin and Oil

Patients often panic when they read labels. They see “Soy Lecithin” on a chocolate bar. They see “Soybean Oil” in a salad dressing. They wonder if they need to put it back on the shelf.

You can breathe a sigh of relief. Soy lecithin is an emulsifier. It is mostly fat. It contains negligible amounts of soy protein. It contains almost no isoflavones. Therefore, it poses very little risk regarding thyroid medication absorption. It also has almost no goitrogenic activity.

Similarly, highly refined soybean oil is pure fat. The proteins have been removed. While soybean oil may be inflammatory due to high Omega-6 content, it is not a thyroid inhibitor. You do not need to treat lecithin with the same caution as a protein shake.

Practical Dietary Strategies for the Hypothyroid Patient

Implementing a Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis diet or a general hypothyroid protocol does not require eliminating soy. It requires strategy. It requires planning. Here is how to structure your day to minimize thyroid medication absorption risks.

Sample Schedule for the Morning Med Taker

- 6:30 AM: Take Levothyroxine with a full glass of water. Do not drink coffee yet. Do not eat food.

- 7:30 AM: Breakfast. You can have coffee now. Use almond, oat, or coconut milk. Avoid soy creamer. Eat eggs, oatmeal, or avocado toast.

- 11:00 AM onwards: The safe window for soy consumption opens. The medication is absorbed.

- 12:30 PM: Lunch. You can have Miso soup. You can have a salad with edamame beans.

- 7:00 PM: Dinner. A stir-fry with tempeh and vegetables is perfectly safe.

Sample Schedule for the Night Med Taker

Some studies suggest taking thyroid meds at night improves absorption. If you do this, you must reverse the rule.

- 6:00 PM: Dinner. This is your last meal. If you want soy, eat it now.

- 6:00 PM – 10:00 PM: Fasting window. Water only.

- 10:00 PM: Take Levothyroxine. Your stomach is empty. The soy protein from dinner has moved out of the stomach.

- 10:30 PM: Sleep.

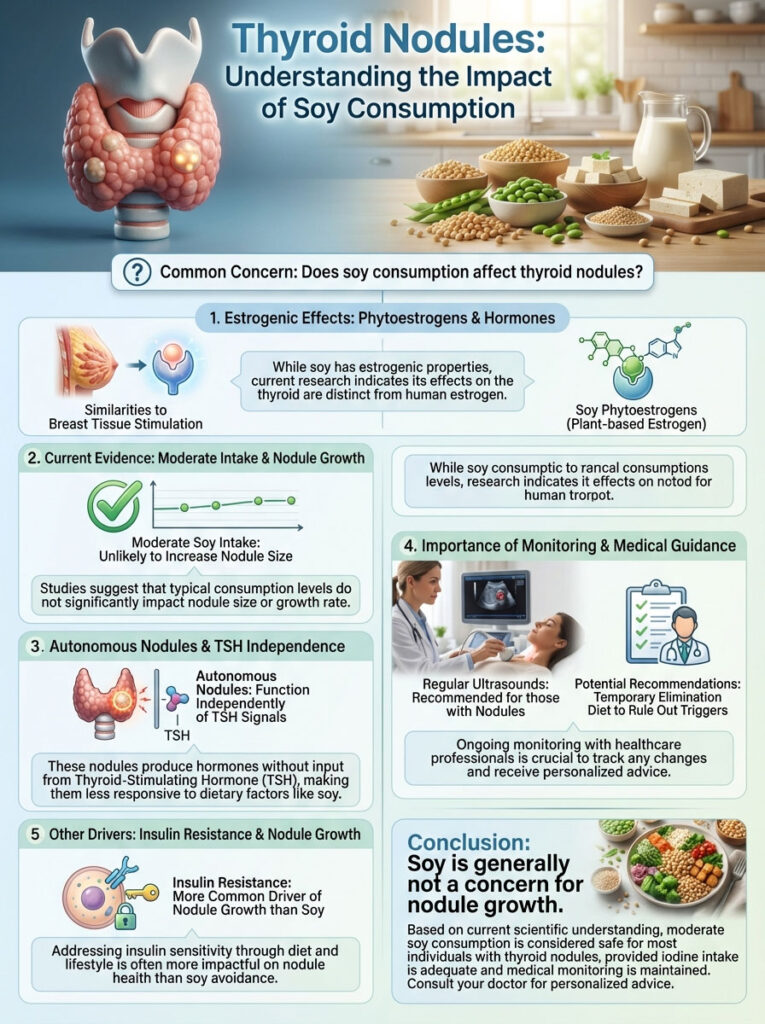

Thyroid Nodules: A Special Consideration

A common question arises regarding thyroid nodules. “If I have a lump on my thyroid, will soy make it grow?” The fear is that the estrogenic effect will stimulate growth. This is similar to how estrogen stimulates breast tissue.

Current evidence suggests this is unlikely. There is no robust data showing that moderate soy consumption causes nodules to increase in size. This applies to benign nodules. However, because nodules can be autonomous, monitoring is key. Autonomous means they function on their own. They do not listen to TSH signals.

If you have nodules, you should be getting regular ultrasounds. If your doctor notices growth, they may suggest a temporary elimination diet. This helps to rule out triggers. But for most, soy is not the driver of nodule growth. Insulin resistance is a more common driver of nodule growth than soy.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The relationship between soy and hypothyroidism is nuanced. The fear surrounding it is largely outdated. It is based on old science and rat studies. We now have better data. We have human studies. We have clinical experience.

Here are the golden rules for navigating this dietary dilemma:

- Check Your Iodine: Soy is only a significant threat if you are iodine deficient. Ensure you are getting adequate iodine. Use iodized salt. Eat sea vegetables. Take a multivitamin if needed.

- Mind the Gap: The most tangible risk is thyroid medication absorption. This is non-negotiable. Maintain a strict 4-hour window between your meds and any soy product.

- Choose Fermented: Tempeh, miso, and natto are superior. They are easier on the gut. They are less likely to trigger autoimmune issues. They are nutrient-dense.

- Avoid Isolates: Stay away from processed soy protein powders. Avoid fake meats made of soy isolate. These are chemically processed and hard on the digestion.

- Listen to Your Body: Bio-individuality is real. If you notice symptoms returning after increasing soy intake, check your TSH. Adjust accordingly.

Is Tofu Safe for Your Thyroid? For the vast majority of patients, the answer is yes. It comes with a side of common sense. It requires proper timing. But it does not require a lifetime ban.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is tofu safe for people with hypothyroidism and Hashimoto’s disease?

Yes, tofu is generally safe as long as you are iodine-sufficient and manage your medication timing correctly. Clinical data suggests that soy isoflavones do not significantly alter TSH levels in healthy, iodine-replete adults, though patients with autoimmune conditions should prioritize organic, non-GMO options.

How many hours should I wait between taking thyroid medication and eating soy?

You must maintain a strict four-hour window between taking levothyroxine and consuming any soy products. Soy protein and fiber have a high affinity for binding to synthetic thyroid hormones in the gastrointestinal tract, which can significantly reduce medication absorption and efficacy.

Does soy act as a goitrogen and interfere with thyroid hormone production?

Soy contains isoflavones like genistein that can inhibit the thyroid peroxidase (TPO) enzyme in laboratory settings, but this effect is negligible in humans with adequate iodine status. Ensuring a daily intake of 150 mcg of iodine effectively neutralizes the goitrogenic potential of moderate soy consumption for most patients.

Which types of soy are best for a thyroid-friendly diet?

Fermented soy products like tempeh, miso, and natto are the superior choices because the fermentation process improves bioavailability and reduces anti-nutrients like phytates. These options are also easier on the digestive system, which is a critical consideration for managing the intestinal permeability often associated with Hashimoto’s.

Should I avoid soy protein isolate if I have an underactive thyroid?

It is highly recommended to limit soy protein isolate (SPI), as it is a highly processed ingredient with concentrated isoflavones and no food matrix. SPI is more likely to interfere with thyroid medication absorption and may contribute to gut irritation compared to whole-food sources like edamame or tofu.

Can soy consumption cause a spike in TPO antibodies in Hashimoto’s patients?

Current clinical evidence does not show a consistent link between moderate soy intake and an increase in thyroid antibodies. However, patients should be cautious of conventional soy treated with glyphosate, as chemical residues can disrupt the gut microbiome and potentially exacerbate the autoimmune response.

Is it safe to use soy milk in coffee shortly after taking levothyroxine?

No, you should avoid adding soy milk to your morning coffee if it falls within the four-hour window after taking your medication. Even small amounts of soy protein can interfere with the delicate absorption process of synthetic hormones like Synthroid, Tirosint, or Levoxyl.

Does iodine deficiency make soy more dangerous for the thyroid?

Yes, iodine deficiency is the primary variable that turns soy into a problematic goitrogen. When iodine is scarce, the thyroid gland cannot properly synthesize hormones, and the inhibitory effects of soy isoflavones on the TPO enzyme become much more clinically significant.

Are soy lecithin and soybean oil harmful to the thyroid?

Soy lecithin and highly refined soybean oil contain negligible amounts of protein and isoflavones, making them safe from a thyroid-interference perspective. You do not need to apply the same strict timing restrictions to these ingredients as you would for high-protein soy foods like tofu or soy milk.

Why do infants on soy formula require higher doses of thyroid medication?

Clinical studies in pediatric endocrinology show that soy protein binds to levothyroxine in the gut, requiring up to a 25% dosage increase for infants with congenital hypothyroidism. This serves as a vital proof of concept for adults regarding the significant impact soy protein has on medication bioavailability.

Can soy isoflavone supplements affect my thyroid function?

Concentrated soy isoflavone supplements pose a higher risk than whole foods because they provide a massive, isolated dose of phytoestrogens. I recommend that hypothyroid patients stick to whole-food soy sources and avoid high-dose genistein pills marketed for menopause relief to prevent potential endocrine disruption.

How much soy can I eat daily without affecting my TSH levels?

For most patients with stable thyroid function and adequate iodine intake, two to three servings of whole-food soy per day are considered safe. Always monitor your TSH levels and clinical symptoms when making significant dietary changes, as individual bio-individuality and gut health can influence how you process goitrogens.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The interactions between diet and endocrine function are complex and vary by individual. Always consult with a qualified endocrinologist or healthcare professional before making significant changes to your diet, iodine intake, or thyroid medication schedule.

References

- American Thyroid Association – thyroid.org – Clinical guidelines on the management of hypothyroidism and dietary interference factors.

- Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – “The effect of soy phytoestrogen supplementation on thyroid status” – Peer-reviewed study on TSH levels and isoflavone intake.

- Journal of Pediatrics – “Unawareness of the effects of soy intake on the management of congenital hypothyroidism” – Research regarding soy formula and medication dosage.

- Thyroid Journal – “Effects of soy protein and soybean isoflavones on thyroid function” – A comprehensive review of human clinical trials and biochemical mechanisms.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences – niehs.nih.gov – Data on endocrine disruptors and the physiological impact of phytoestrogens.

- Journal of Nutrition – “Soy Protein Isolate and Thyroid Function” – Analysis of processed soy vs. whole food soy on endocrine markers.