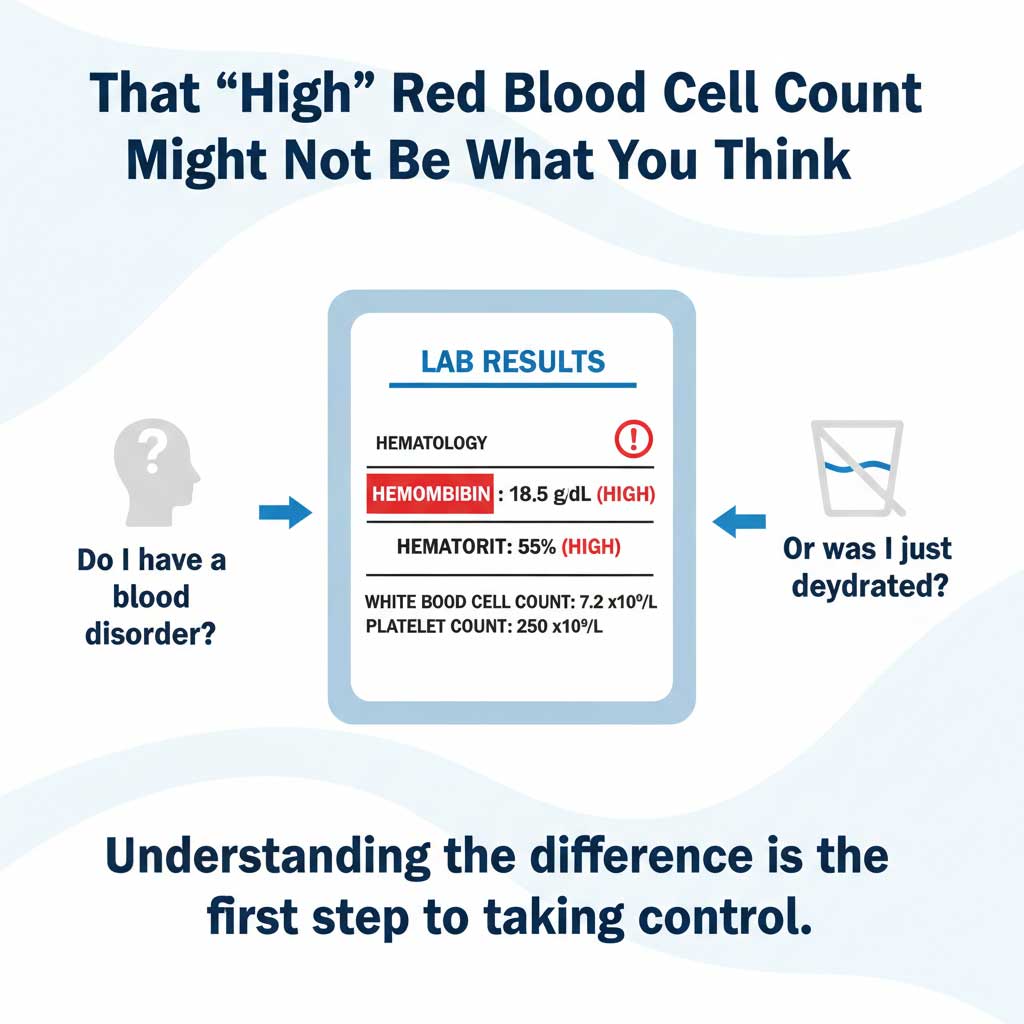

You open your lab results, and your eyes scan down the list. Most are in the comfortable green of the “normal” range. But then you see it, flagged in jarring red: “Hemoglobin: HIGH,” “Hematocrit: HIGH.”

Your heart sinks. Your mind immediately leaps to the scariest conclusions—blood disorders, cancer, words you’ve only heard in hushed tones. It’s a moment of pure, visceral anxiety, where two numbers on a screen can suddenly feel like a verdict on your health.

- The "Soup Analogy": A Deep Dive into Why Dehydration Skews Your CBC

- The Clinician's Dilemma: Dehydration vs. Disease

- Looking for Clues: The "Dehydration Footprint" on Other Lab Tests

- Dehydration vs. True Polycythemia: A Comparative Table

- Your Proactive Plan: How to Prepare for Your CBC Test

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

But what if those numbers aren’t telling a story of a new disease, but a much simpler story about the water you didn’t drink this morning?

The answer is a definitive yes. Dehydration is one of the most common—and most misunderstood—reasons for a lab report to show a falsely high red blood cell count. This guide is different from a simple list of facts. We’re going to pull back the curtain and walk you through this phenomenon just like an experienced clinician would. We’ll explore the “why” behind the numbers, show you how to spot the hidden clues in your own lab report, and give you the confidence to have a smarter conversation with your doctor.

At HealthCareOnTime.com, we believe an informed patient is an empowered patient. Let’s turn that anxiety into expertise.

The “Soup Analogy”: A Deep Dive into Why Dehydration Skews Your CBC

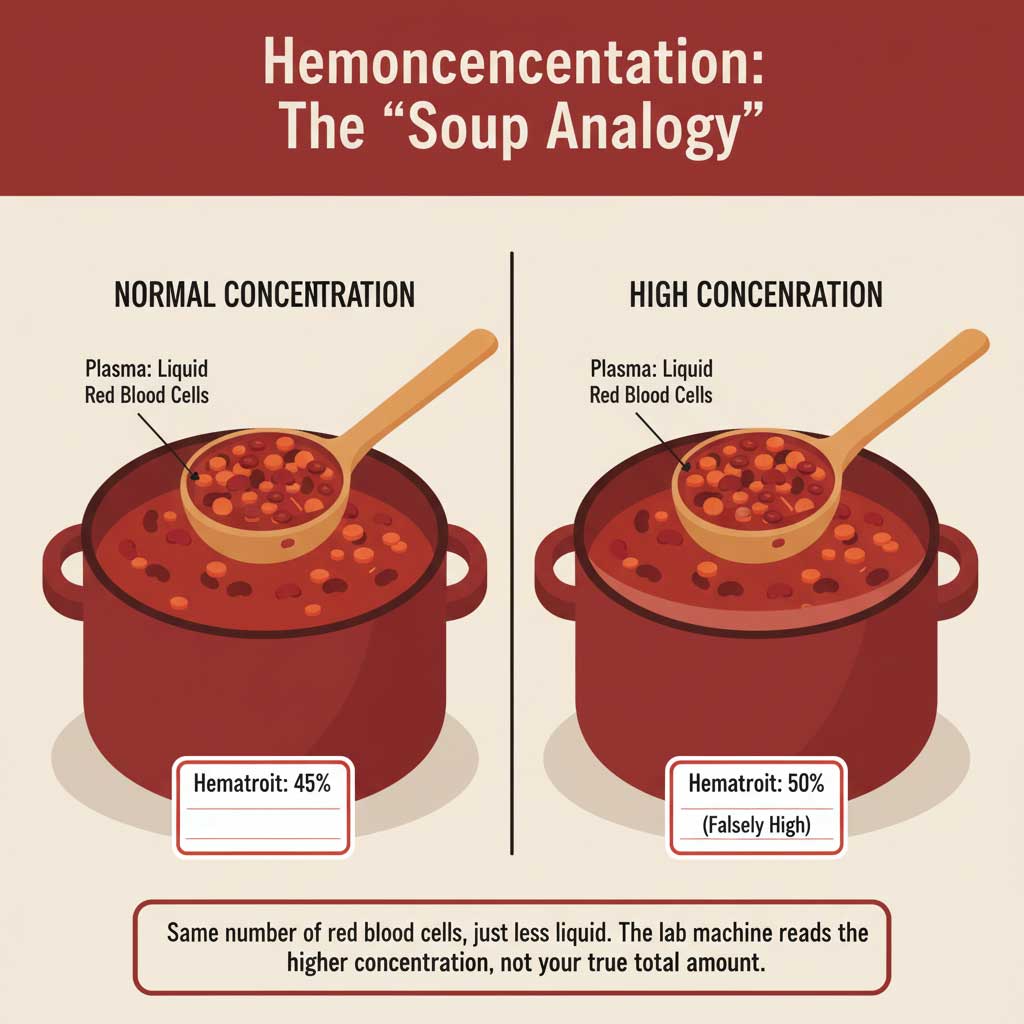

To truly understand why a lack of water can make your blood count look high, we need to move beyond simple facts and talk about a core concept that lab technicians and doctors know well: hemoconcentration. It sounds complicated, but the idea is simple.

The Expert’s Analogy: Boiling the Soup

Imagine your blood is a large pot of vegetable soup. The vegetables—the carrots, celery, and potatoes—are your red blood cells (RBCs). The broth is your blood plasma, the clear, yellowish liquid part of your blood that is about 92% water.

A Complete Blood Count (CBC) is like taking one small ladle of that soup and analyzing how packed with vegetables it is.

Now, if you let that soup simmer on the stove for an hour and boil off half the broth, what happens? You haven’t added any more vegetables. The total number of vegetables in the pot is the same. But your next ladle of soup will be much thicker, richer, and far more “concentrated” with vegetables.

This is exactly what happens to your blood when you’re dehydrated. You haven’t magically grown more red blood cells; you’ve just lost some of the watery plasma they float in. The lab machine analyzes this thicker, more concentrated sample and reports a higher number.

How This Shows Up on Your Report: A Line-by-Line Breakdown

This “concentration effect” is what causes those specific red flags on your CBC. A lab machine is a “concentration checker,” not a “total body counter.”

Hematocrit (Hct): The Most Direct Measure

Why does hematocrit increase with dehydration? Because hematocrit is simply the percentage of your blood’s volume that is made up of red blood cells. In our soup analogy, it’s the percentage of the ladle that is filled with vegetables versus broth. When you remove the watery plasma, the percentage of red cells naturally and falsely goes up. A perfectly healthy hematocrit of 45% can easily become a “high” 50% just from skipping water.

Hemoglobin (Hgb) & Red Blood Cell (RBC) Count

These are also concentration measurements. The machine is counting the amount of hemoglobin (in grams per deciliter) or the number of red blood cells (in cells per microliter) within a tiny, fixed volume of blood. When that tiny volume is more densely packed with cells because the plasma has decreased, the numbers inevitably go up. This is the direct answer to “can dehydration cause high RBC count?”

The Clinician’s Dilemma: Dehydration vs. Disease

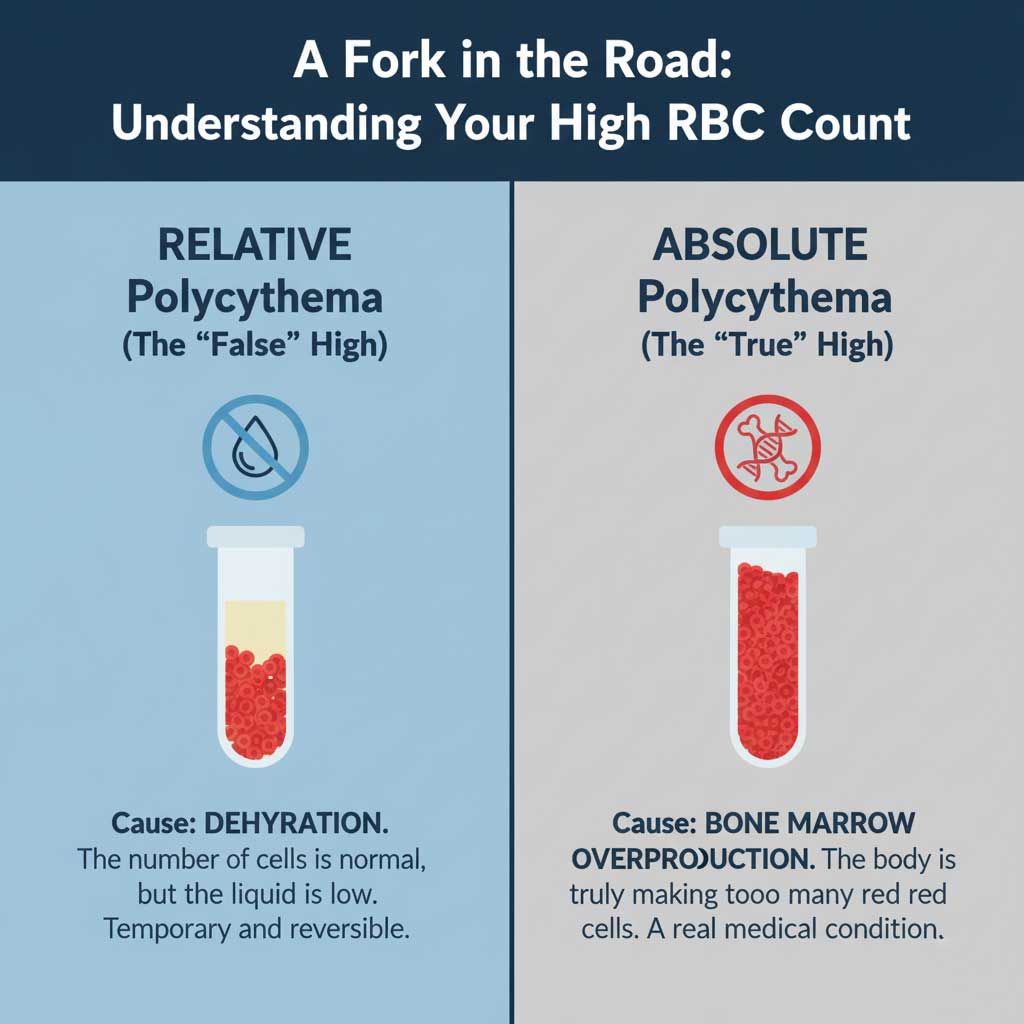

When a doctor sees high hemoglobin and hematocrit, they are faced with a critical diagnostic fork in the road. Their expertise lies in figuring out which path to take. Is this a simple false alarm, or the first sign of a true disease?

Path #1: Relative Polycythemia (The “False” High)

This is the medical term for the situation we’ve been describing. It’s called “relative” because your red blood cell count is only high relative to the low volume of your blood plasma. It’s a temporary state caused almost exclusively by dehydration. This is, by far, the most common reason for an unexpectedly high red blood cell count in the general population. It’s a reflection of your fluid status, not your bone marrow’s health.

Path #2: Absolute Polycythemia (The “True” High)

This is the more serious path, where your body is actually overproducing red blood cells. This is a real medical condition that requires investigation. It can be:

- Secondary: Your bone marrow is healthy, but it’s being told to make more red cells by another problem. This is common in heavy smokers, people with severe lung disease (COPD), or those with obstructive sleep apnea, where the body makes more red cells to carry scarce oxygen.

- Primary: A much rarer condition where the bone marrow itself is the problem. This is a type of bone marrow cancer called Polycythemia Vera, where the “factory” that makes red cells is stuck in the “on” position.

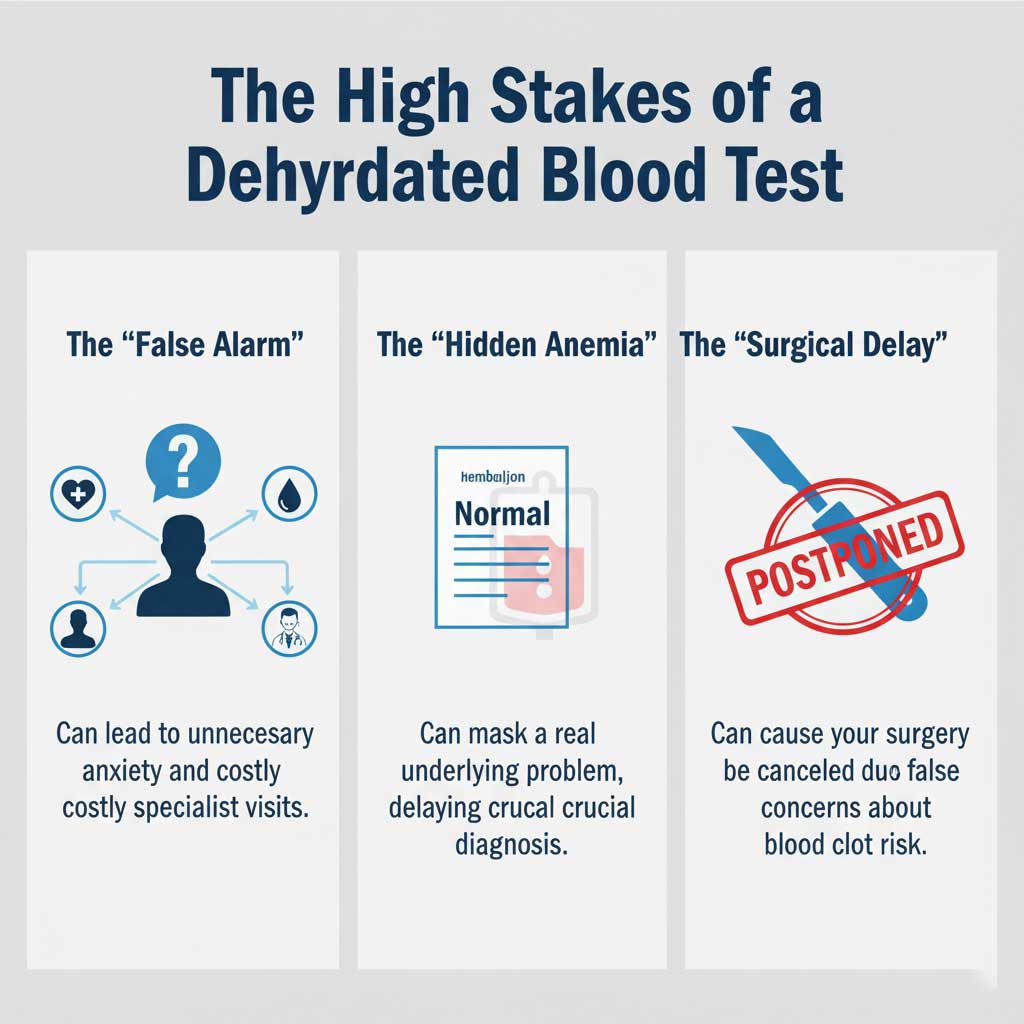

Why Getting It Right Matters So Much: High-Stakes Consequences

Distinguishing between these two paths is critical, because taking the wrong one can have serious consequences for you, the patient.

The “False Alarm” and the Anxiety Cascade

The most common outcome of a dehydrated blood sample is a cascade of unnecessary anxiety and medical testing. You get a call from your doctor’s office expressing concern. You’re referred to a hematologist (a blood specialist). You spend weeks worrying about potential cancer diagnoses. You undergo more expensive tests, only to have the specialist take one look at your full lab panel and ask, “Were you dehydrated?” The final diagnosis is a relief, but the emotional and financial cost was completely avoidable.

Masking a Real Problem: The Hidden Anemia Trap

This is a more subtle, but equally dangerous, clinical trap. Imagine a patient has a slow, hidden GI bleed from an ulcer, and their true hemoglobin is a mildly anemic 11.5 g/dL. This should trigger an investigation. However, if they get their blood drawn while they are also dehydrated, the hemoconcentration could artificially inflate that number to a seemingly “normal” 12.5 g/dL. In this case, the dehydration effectively hides the anemia, causing a dangerous delay in finding and treating the source of the blood loss.

The Pre-Surgical Delay

A patient is scheduled for a knee replacement and gets their pre-operative labs done. Their CBC shows a hematocrit of 51%. The anesthesiologist, whose primary job is to ensure patient safety, sees this number and worries. High hematocrit (“thick blood”) can increase the risk of developing dangerous blood clots, like a Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) or a life-threatening Pulmonary Embolism (PE), during and after surgery. They may postpone the surgery until the high blood count can be investigated by a specialist, causing immense frustration, wasted time, and logistical problems for the patient—all from a preventable, dehydrated sample.

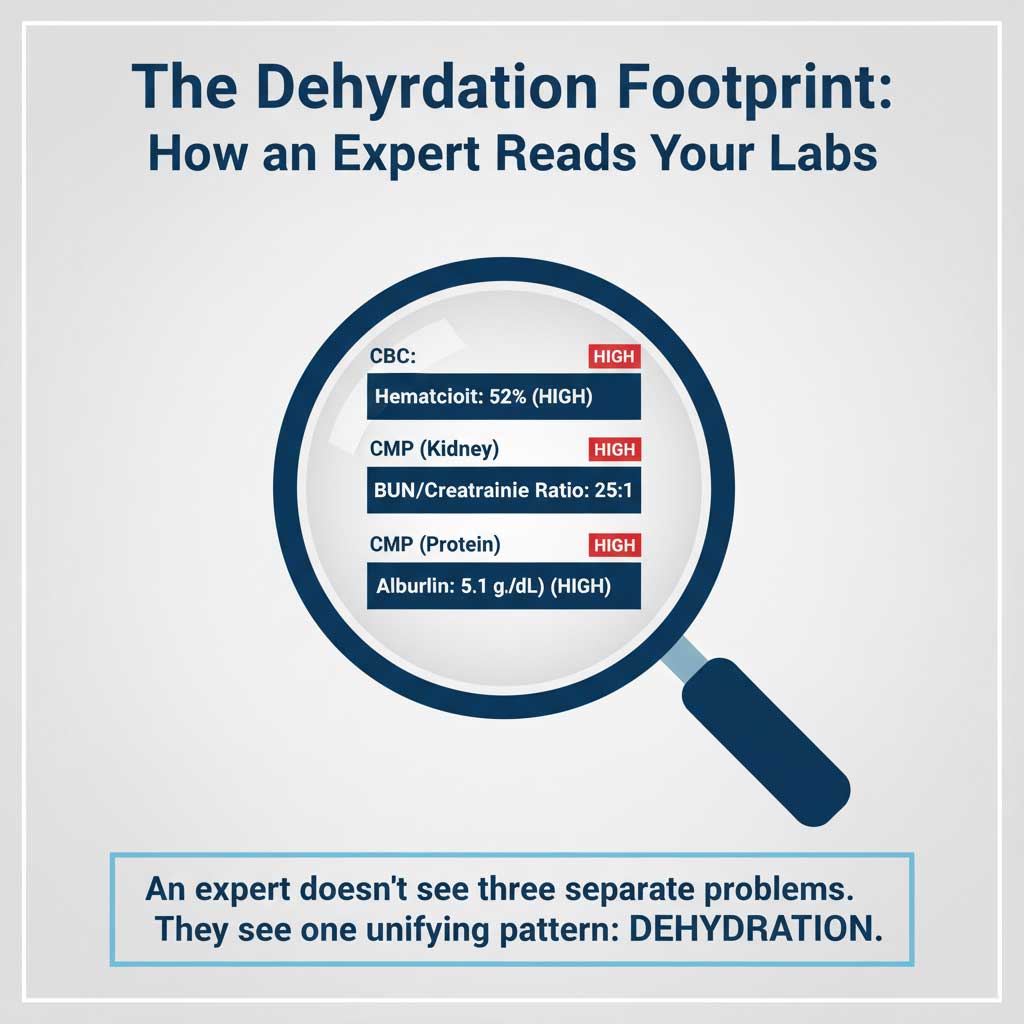

Looking for Clues: The “Dehydration Footprint” on Other Lab Tests

An expert clinician never makes a judgment based on one number from one test. They look for a pattern of evidence across all your lab work. Dehydration leaves a very specific “footprint.” Here are the other clues they look for to confirm that dehydration and red blood cells are the real story.

The Kidney Signature: The Telltale BUN:Creatinine Ratio

This is the number one clue that doctors look for on your Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP).

- The Clinical Insight: When you’re dehydrated, your body panics and goes into extreme water-conservation mode. As your kidneys filter blood, they desperately try to pull water back into your body. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) is a small waste product that gets pulled back along with the water, causing its level in the blood to rise sharply. Creatinine is a larger waste product that mostly doesn’t get reabsorbed.

- The Real-World Numbers: In a healthy person, the ratio of BUN to creatinine is usually around 15:1. In a dehydrated person, that ratio will often be greater than 20:1. So, if your CMP shows a BUN of 30 mg/dL and a creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL, that’s a 30:1 ratio. A seasoned doctor doesn’t see kidney failure; they see a patient who needed a glass of water.

The Protein and Electrolyte Signature

The pattern continues on your CMP. When plasma volume drops, everything that floats in it becomes more concentrated. You may also see a high Albumin (the main protein in your blood) and slightly elevated electrolytes like Sodium and Chloride.

Can dehydration cause elevated WBC?

Yes, this is another small piece of the puzzle. While the main effect of hemoconcentration lab results is on the densely packed red blood cells, your White Blood Cells (WBCs) also become more concentrated in the reduced plasma volume. This can cause a slight, mild elevation in your total WBC count, further contributing to the overall picture of a concentrated blood sample.

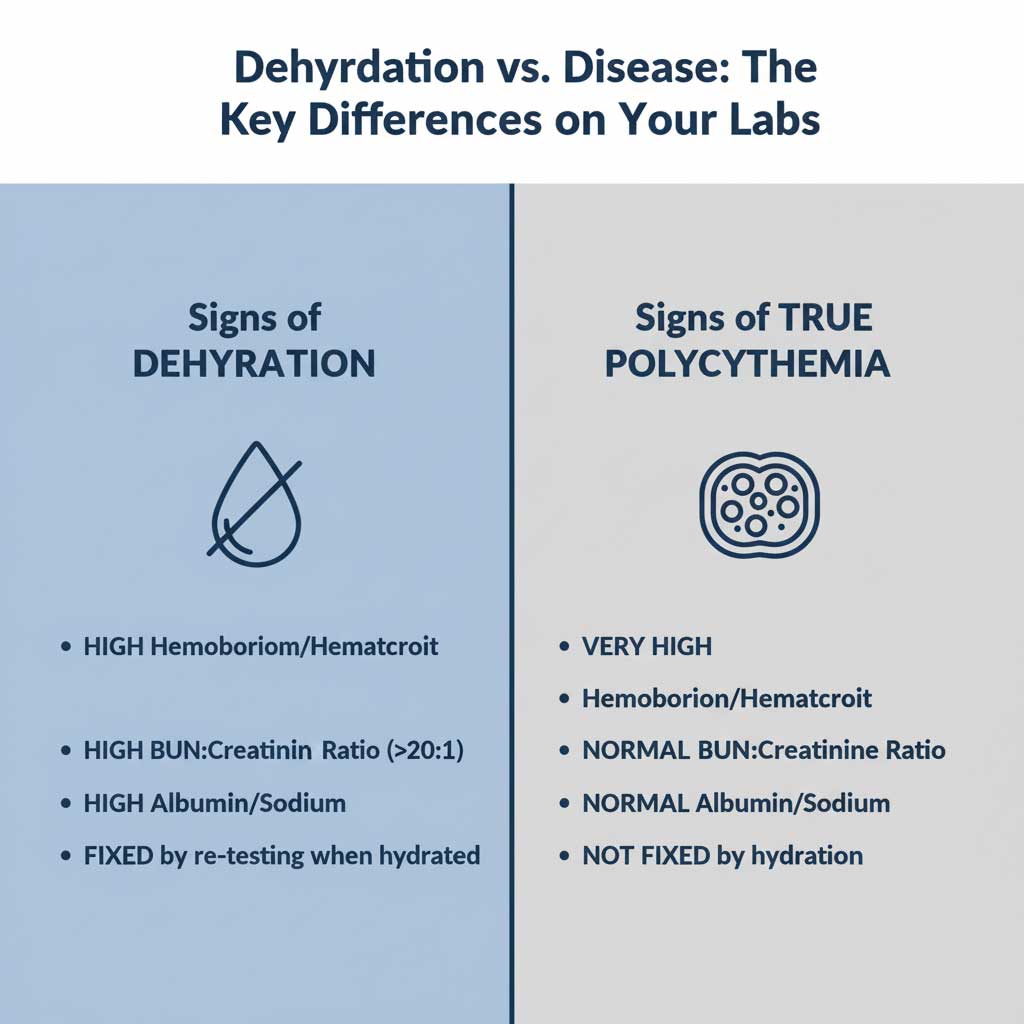

Dehydration vs. True Polycythemia: A Comparative Table

| Lab Finding | The Pattern for DEHYDRATION (Relative Polycythemia) | The Pattern for TRUE POLYCYTHEMIA (e.g., Polycythemia Vera) |

| CBC Panel | High Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, RBC Count. | Very High Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, RBC Count. |

| CMP (Kidney) | High BUN, with a BUN:Creatinine Ratio > 20:1. | Normal BUN and Creatinine (unless a separate kidney issue exists). |

| CMP (Other) | High Albumin, Sodium, Chloride. | Normal Albumin and electrolytes. |

| Other Tests | Corrects upon rehydration and re-testing. | Does not correct with hydration. May have a low EPO hormone level and a positive JAK2 gene mutation test. |

| Clinical Picture | Patient may feel thirsty, have dry mouth, or have recently been sick/exercised. | Patient may have symptoms like itching after a shower (aquagenic pruritus), redness of the face, fatigue, and headaches. |

Your Proactive Plan: How to Prepare for Your CBC Test

The fix for all this potential confusion is remarkably simple. You don’t need to overdo it; the goal is just to be normally hydrated.

The Hydration Protocol

- 24 Hours Before: Make a conscious effort to drink water consistently throughout the day. Avoid diuretics like alcohol and limit excessive caffeine, as these can work against your hydration efforts.

- Morning Of: Aim to drink 16 ounces (two glasses) of plain water in the 1 to 2 hours before your blood draw. This is the perfect amount to ensure your plasma volume is normal and your results are accurate.

When to Retest

If your hemoglobin was high and you suspect dehydration was the cause, should you get another test? Absolutely. Discuss it with your doctor. A simple re-test after ensuring good hydration can prevent a cascade of unnecessary specialist visits, anxiety, and cost. It’s the smartest and simplest next step.