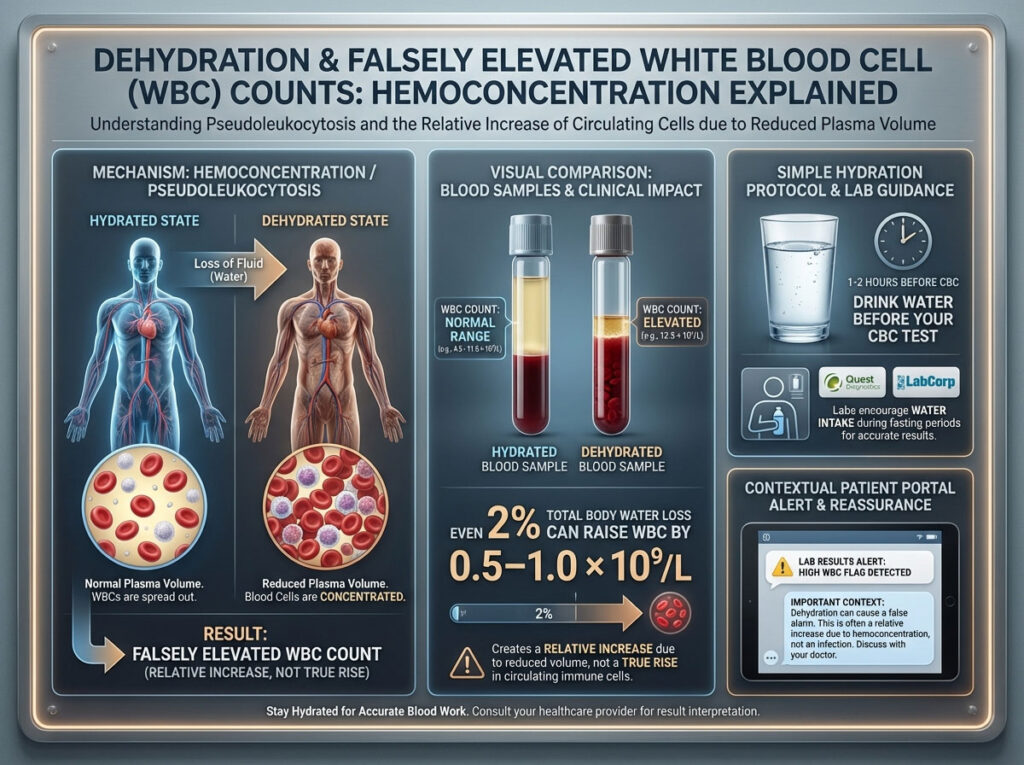

Yes, dehydration can cause a falsely high White Blood Cell (WBC) count. This clinical phenomenon is formally known as hemoconcentration or pseudoleukocytosis. When your body lacks sufficient fluid, the volume of plasma in your blood decreases. This artificially concentrates the cellular components, including white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.

Table of Contents

Consequently, the laboratory analysis shows a higher number of cells per microliter of blood. Research indicates that a total body water loss of just 2% can raise WBC readings by approximately 0.5–1.0 × 10⁹/L. This is considered a “relative” increase. The absolute number of white blood cells circulating in your body usually remains normal, but they are crowded into a smaller volume of fluid. Drinking water to restore plasma volume before a blood draw is the most effective way to prevent this error and ensure accurate diagnostic results.

Dehydration Can Trick Your CBC Into Showing a High WBC

You open your patient portal. You scan the column for results, hoping to see a clean bill of health. Most numbers are green. Then you see it. Your White Blood Cell (WBC) count is flagged in red as “High” or “Abnormal.”

Immediate panic often sets in. We are conditioned to associate a high WBC count with infection, inflammation, or frightening diagnoses like leukemia or autoimmune disorders. The mind races to the worst-case scenario. However, before you spiral into anxiety, ask yourself a simple, practical question. Did you drink enough water this morning?

The reality of medical diagnostics is that your hydration status plays a massive, often overlooked role in the accuracy of your numbers. A dehydration blood test result is one of the most common reasons for a “false positive” on a Complete Blood Count (CBC).

If you fasted incorrectly by avoiding water. If you simply forgot to hydrate. Or if you drank coffee instead of water. Your blood volume changes. This article is your definitive, expert-level guide to understanding can dehydration cause high WBC, differentiating it from true infection, and mastering the exact hydration protocol you need to follow before your next appointment.

We will break down the physiology of hemoconcentration. We will look at why leading providers like Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp actually encourage you to drink water during a fast. And we will provide a comprehensive step-by-step plan to ensure your next blood draw is accurate, painless, and free of false alarms.

The Physiology of Blood: Why Hydration Matters

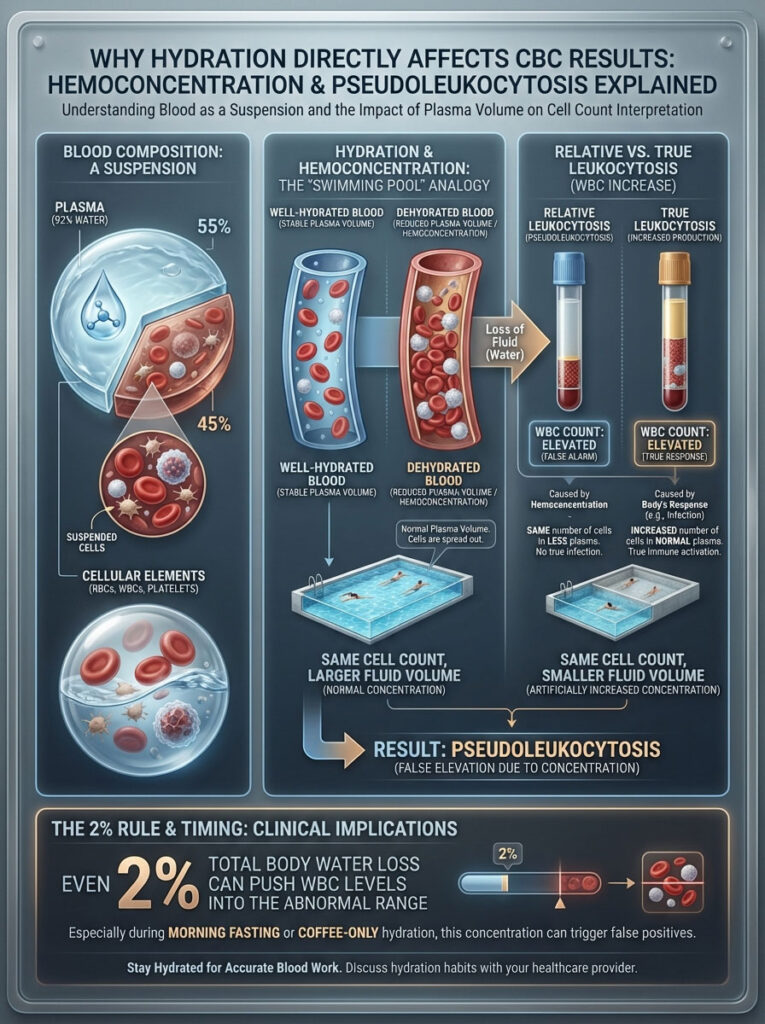

To understand why dehydration and white blood cell count are inextricably linked, you must first understand what a blood test actually measures. A standard CBC does not count every single cell in your body. It counts the density of cells in a tiny, specific sample.

The Composition of Human Blood

Your blood is not a uniform liquid. It is a suspension. Roughly 55% of your blood is plasma. Plasma is mostly water (about 92%), mixed with proteins, salts, and enzymes. The remaining 45% consists of cellular material: Red Blood Cells (RBCs), White Blood Cells (WBCs), and Platelets.

This balance is critical. In a healthy, well-hydrated state, the ratio of fluid to cells is stable. This stability allows the automated hematology analyzers in the lab to provide an accurate reflection of your health.

Understanding Hemoconcentration

When you are dehydrated, you lose plasma volume. The water component of your blood evaporates through breath, is excreted through urine, or is lost through sweat. However, the cellular components do not evaporate. They remain in the vessels.

Think of it like a swimming pool. If you have a pool with ten swimmers and you drain half the water, the pool looks incredibly crowded. But you still only have ten swimmers. The population hasn’t changed; the environment has just shrunk.

This is hemoconcentration. The density of the cells increases because the liquid volume decreases.

In medical terms, this is called relative leukocytosis. The “relative” part is the key distinction. It means the count is high relative to the volume of blood, not because the body is producing more cells.

True leukocytosis is different. That happens when your bone marrow actively produces more white blood cells to fight an infection. In that case, the “swimming pool” actually has twenty swimmers instead of ten, regardless of the water level.

The Concept of Pseudoleukocytosis

Doctors often refer to high WBC after dehydration as pseudoleukocytosis. This translates literally to “false increase in white cells.”

This is not a lab error or a machine malfunction. The machine counted correctly. The sample itself was simply too concentrated.

Studies published in clinical journals have shown significant shifts in CBC parameters based on hydration status alone. For example, a 2% reduction in total body water can skew results enough to push a high-normal patient into the “abnormal” range. This is particularly common in morning blood draws, where patients wake up in a naturally dehydrated state after sleeping for eight hours without fluid intake.

This is why pseudoleukocytosis is such a common confounding factor in preventative medicine. Patients often fast aggressively, avoiding all liquids. They wake up dehydrated. They drink coffee, which is a diuretic. And then they are surprised when their WBC dehydration numbers come back elevated, triggering unnecessary follow-up appointments and anxiety.

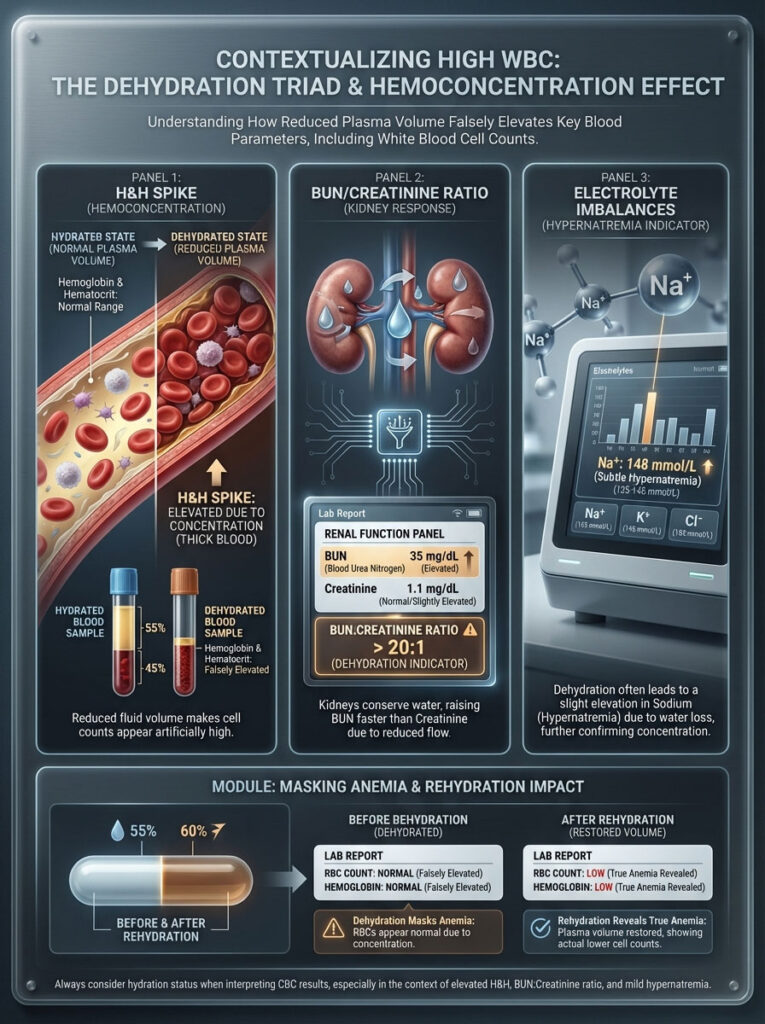

Dehydration Markers: Putting WBC in Context

If you are trying to determine can dehydration cause high WBC in your specific case, you should never look at the white blood cells in isolation. Dehydration is a systemic issue. It affects the concentration of everything in your blood, not just one cell type.

When hemoconcentration occurs, it creates a specific, recognizable footprint across your entire lab report. A savvy patient or clinician looks for the “Dehydration Triad” rather than just a single high number.

The Dehydration Triad

1. The H&H (Hemoglobin and Hematocrit) Spike

The most reliable indicator of dehydration is typically not the WBC count alone. It is the Hematocrit.

Hematocrit measures the percentage of your blood volume that is made up of red blood cells. Since red blood cells are the largest and most abundant cellular component, they are the most affected by volume loss.

If your dehydration blood test shows a high WBC count, look immediately at your Hematocrit and Hemoglobin. If both of these are also near the top of the reference range or elevated, it is highly probable that plasma volume loss is the culprit. We often call this “thick blood” in layman’s terms.

2. BUN/Creatinine Ratio

Your Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP) offers clues that corroborate the blood count. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) and Creatinine are waste products filtered by your kidneys.

When you are dehydrated, your kidneys enter survival mode. They aggressively conserve water to maintain blood pressure. This causes BUN levels to rise disproportionately faster than Creatinine levels. A BUN-to-Creatinine ratio greater than 20:1 is a classic clinical sign of dehydration. If you see a high WBC count alongside a ratio of 25:1, the diagnosis of dehydration is almost certain.

3. Electrolyte Imbalances

You might also see shifts in sodium or potassium. While these are more complex and depend on the type of dehydration (sweat loss vs. water restriction), mild hypernatremia (high sodium) often accompanies hemoconcentration.

The Hidden Mask: Dehydration and Anemia

There is a complex scenario where dehydration can actually hide a problem. If a patient is anemic (low red blood cells) but is also severely dehydrated, the hemoconcentration can artificially raise their red blood cell count up to the “normal” range.

In this case, the dehydration masks the anemia. Once the patient is rehydrated, their numbers drop, revealing the underlying deficiency. This underscores why proper hydration is not just about avoiding high numbers; it is about ensuring the numbers are true.

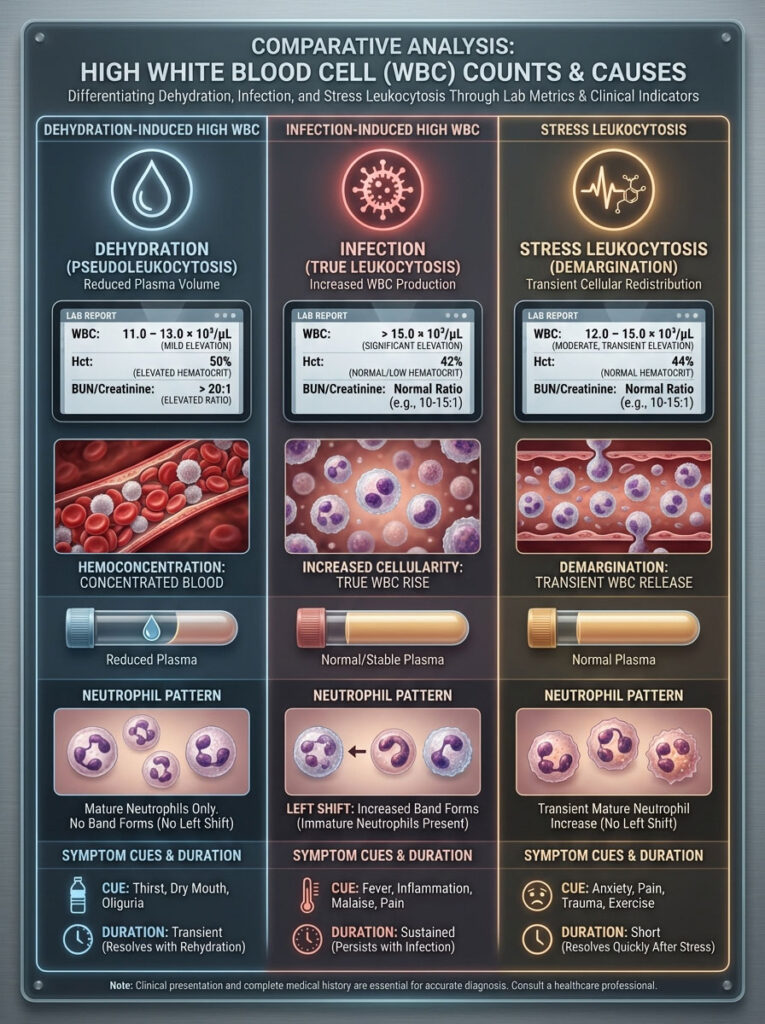

Comparative Analysis: Is it Dehydration, Infection, or Stress?

The greatest fear patients face when seeing an abnormal result is distinguishing between a false high white blood cells result and a serious medical issue like a bacterial infection or leukemia. While only a doctor can diagnose you, there are distinct patterns that separate dehydration leukocytosis from infectious leukocytosis.

Deciphering Your Results

Infection Signs:

Infection usually triggers a biological response called a “Left Shift.” This means your body is pumping out immature neutrophils (often listed as “Bands” on a lab report) to fight a war. You will often feel sick. You may have a fever, chills, or localized pain.

Dehydration Signs:

Dehydration rarely causes a massive spike. It typically bumps the numbers up by 15% to 20%. You will likely feel thirsty, tired, or dizzy. But you likely won’t have a fever. The elevation is usually uniform across cell types.

The Role of Stress (Stress Leukocytosis):

Stress is the third variable, often called the “White Coat Effect.” If you are terrified of needles, your body dumps adrenaline. Adrenaline causes white blood cells that are sticking to your blood vessel walls (the marginated pool) to release into the bloodstream (the circulating pool). This is known as “demargination.”

This can happen in minutes. If you combine dehydration with stress, you can see a surprisingly high WBC count in a perfectly healthy person.

Dehydration vs. Infection Indicators

| Feature | Dehydration-Induced High WBC | Infection-Induced High WBC | Stress-Induced (Needle Fear) |

| WBC Count Magnitude | Mild Elevation (e.g., 11k–13k) | Moderate to High (Often >15k) | Mild to Moderate (Transient) |

| Hematocrit | Elevated (Hemoconcentration) | Normal or Low (Anemia of inflammation) | Normal |

| Neutrophils | Normal distribution | “Left Shift” (High immature cells) | High Mature Neutrophils |

| Physical Symptoms | Thirst, dry mouth, dark urine | Fever, chills, localized pain | Anxiety, rapid heart rate |

| Plasma Volume | Low | Normal | Normal |

| BUN/Creatinine | Ratio > 20:1 | Ratio usually normal | Ratio usually normal |

| Duration | Resolves after rehydration | Persists until infection clears | Resolves in minutes/hours |

How to Hydrate Properly Before a Blood Draw

Now that we have established that can dehydration cause high WBC is a definitive “Yes,” the solution is straightforward. You must engage in strategic hydration.

Many patients fail to hydrate before blood draw appointments because they misunderstand the rules of fasting or they simply drink the wrong fluids at the wrong times.

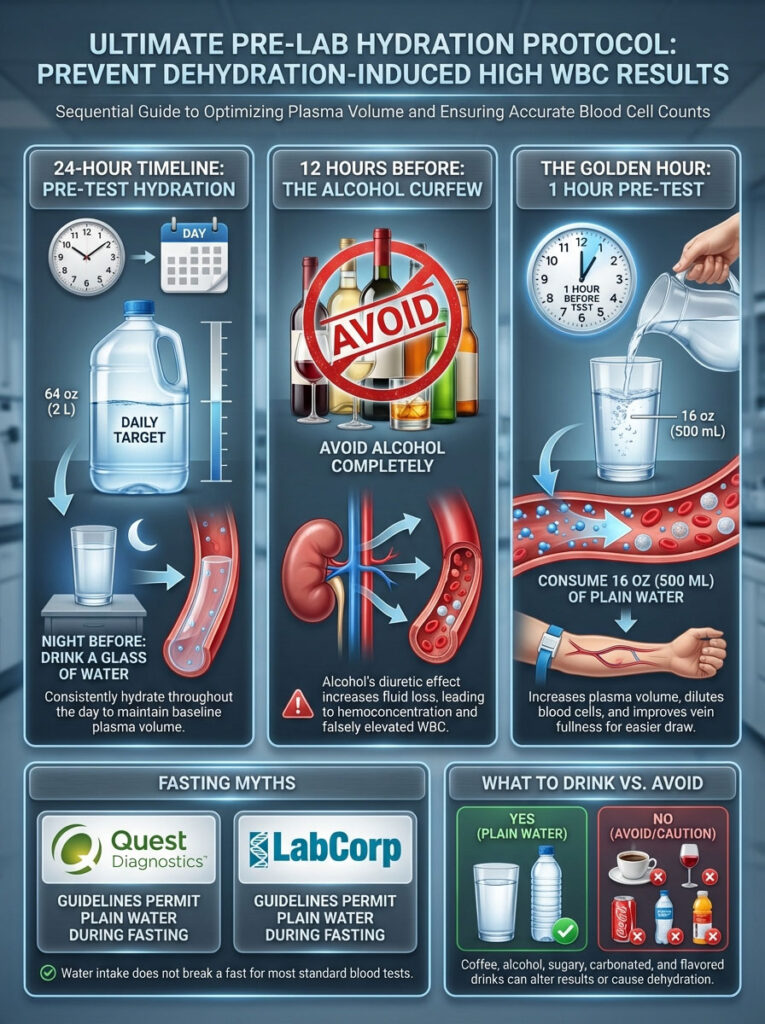

The Ultimate Pre-Lab Hydration Protocol

To ensure your Complete Blood Count (CBC) is accurate, you need to normalize your plasma volume before the needle goes in.

1. The 24-Hour Timeline: The Pre-Game

Hydration does not happen instantly. It happens at the cellular level. Drinking a gallon of water five minutes before the test will not fix cellular dehydration; it will just fill your bladder.

- The Day Before: You should aim to consume your baseline water requirement. For most adults, this is around 64 oz (approx. 2 liters). This ensures that your tissues are hydrated and your baseline blood volume is stable.

- The Night Before: Ensure you have a glass of water before bed. We lose significant moisture through breathing while we sleep.

2. 12 Hours Before: What to Avoid

Avoid alcohol completely. Alcohol is a diuretic. It inhibits the release of vasopressin, an antidiuretic hormone. This forces your kidneys to excrete more fluid than you consume. Drinking alcohol the night before a blood test is the fastest way to trigger hemoconcentration.

3. The “Golden Hour” Rule

This is the most critical step for vein access and result accuracy.

Drink 16 oz (approx. 500 mL) of plain water exactly 1 hour before your appointment.

Why one hour? It takes about 45 to 60 minutes for ingested water to be absorbed by the gastric system, enter the vascular system, and boost plasma volume. This timeframe ensures your veins are plump and full for the phlebotomist, but it is not so much water that it dilutes your sodium levels excessively.

Fasting Myths Busted: Quest & LabCorp Policies

There is a persistent, harmful myth that “Fasting” means “Nothing by Mouth” (NPO). This is incorrect for 99% of routine labs.

Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp patient preparation guidelines are clear. When fasting for glucose or lipid panels, you should drink water.

Fasting means no calories. No fats. No sugars.

Water has zero calories. Zero fats. Zero sugars.

Depriving yourself of water makes the blood draw difficult, increases pain, and ruins the accuracy of the dehydration blood test parameters. Unless your doctor specifically tells you “NPO” (usually for surgery or specific gastric procedures), water is mandatory.

What Type of Water?

Stick to plain tap, filtered, or spring water.

- Avoid Carbonated Water: While generally safe, the gas can cause bloating and discomfort during the draw.

- Avoid “Vitamin” Waters: Many contain hidden sugars or additives that break a fast.

- Temperature: Room temperature water is often easier to drink in volume than ice-cold water, but this is a matter of preference.

What to Drink vs. Avoid Before a Blood Draw

| Beverage Type | Can I Drink It? | When to Stop? | Effect on Blood Work |

| Plain Water | YES | Drink until the appointment | Improves accuracy & vein access |

| Black Coffee | NO | 8-12 hours prior | Diuretic (Dehydrates); Can skew Cortisol/Glucose |

| Alcohol | NO | 24 hours prior | Severe Dehydration; Liver enzyme spikes |

| Soda / Juice | NO | 8-12 hours prior | Spikes Glucose; Ruins Lipid Panel |

| Electrolyte Drinks | Use Caution | 8-12 hours prior | Sugars break fast; Electrolytes alter BMP results |

| Tea (Unsweetened) | NO | 8-12 hours prior | Contains Caffeine/Tannins; mild diuretic |

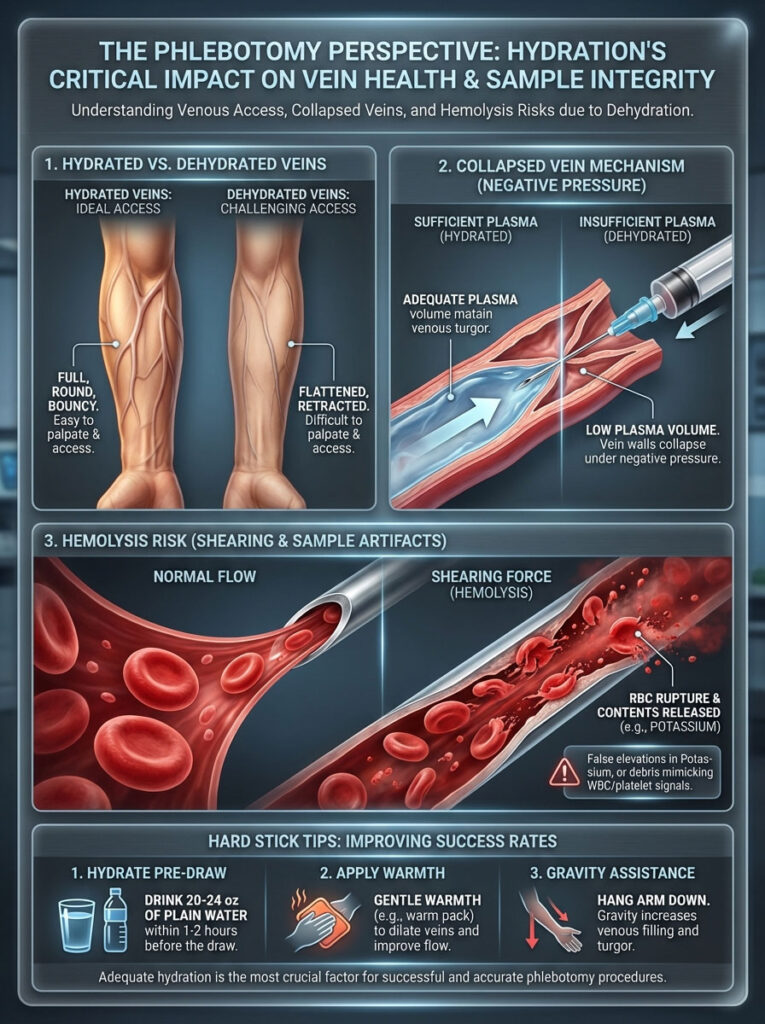

The Phlebotomy Perspective: Vein Health and Hemolysis

Hydration is not just about the numbers on the page. It is about the physical experience of the blood draw and the integrity of the sample collected.

If you have ever had a phlebotomist dig around in your arm, or if you have had to get stuck multiple times to get a viable sample, you were likely dehydrated.

Why Phlebotomists Love Hydrated Patients

Phlebotomists rely on venous pressure (turgor) to locate a vein. When you hydrate before blood draw appointments, you increase the fluid pressure in the vessels. They feel bouncy, resilient, and distinct from the surrounding tissue.

A hydrated vein is like a fully inflated balloon; it holds its shape. A dehydrated vein is like an under-inflated balloon; it is squishy and hard to find.

Preventing Vein Collapse

When you are dehydrated, your plasma volume is low. The pressure inside the vein drops.

When the phlebotomist attaches the vacuum tube (Vacutainer) to the needle, it creates a strong negative pressure to suck the blood out. If you are dehydrated, the suction from the tube overcomes the pressure in your vein. The walls of the vein suck together and close shut. This is a “collapsed vein.” The blood flow stops instantly, and the phlebotomist has to withdraw the needle and stick you again.

Reducing Hemolysis Risks

This is critical for WBC dehydration interpretation. When a draw is difficult, the blood flows slowly and turbulently. The suction forces blood cells through the tiny needle opening under high stress.

This causes hemolysis. The red blood cells shear and burst apart.

When red blood cells burst, they release their intracellular contents into the serum. This ruins potassium readings (causing false high potassium) and complicates the lab’s ability to count cells accurately. It can create cellular debris that automated machines might misread as platelets or white blood cells, complicating the pseudoleukocytosis issue.

Tips for “Hard Stick” Patients

If you have been told you are a “hard stick” or have “rolling veins,” you must be aggressive with your hydration.

- Double Down: Drink closer to 20-24 oz in the hour before.

- Warmth: Wear a warm sweater or coat until the moment of the draw. Cold constricts veins; heat dilates them.

- Gravity: Let your arm hang down while waiting in the lobby to increase blood pooling in the extremity.

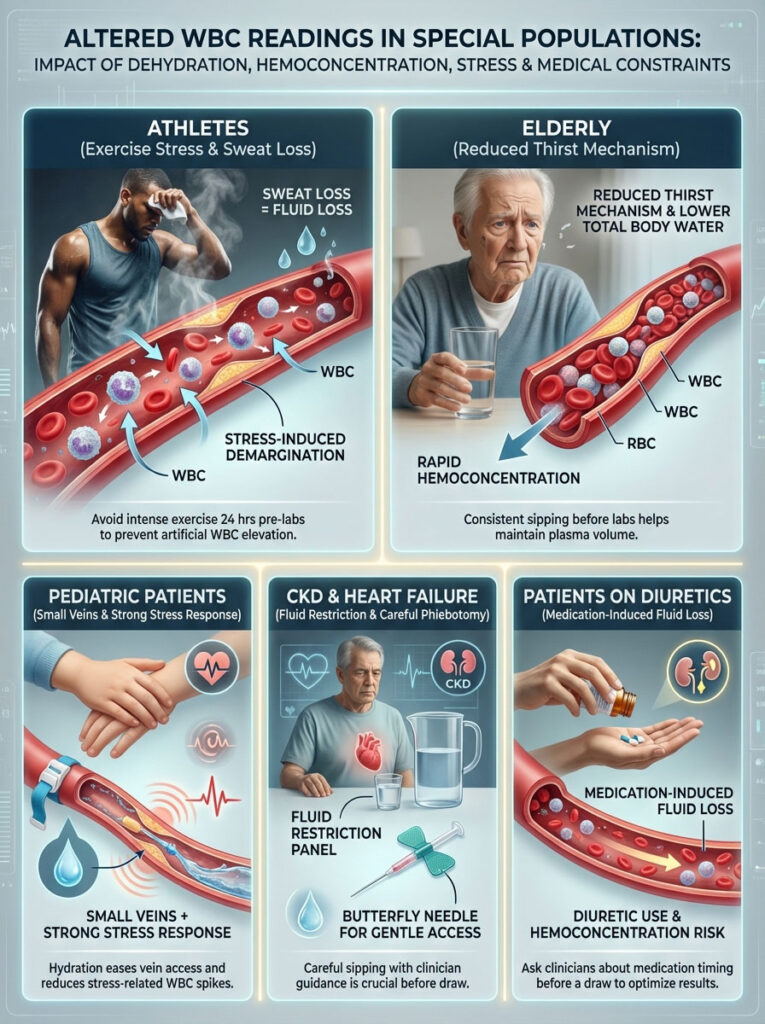

Special Populations and Scenarios

The impact of dehydration and white blood cell count is not uniform across all people. Certain groups are more susceptible to hemoconcentration or have specific physiological challenges that require tailored advice.

Athletes and Post-Exercise Leukocytosis

If you are an athlete or a fitness enthusiast, you need to be particularly careful with timing. Intense exercise causes two things to happen simultaneously:

- Dehydration: You sweat, losing plasma volume.

- Demargination: Physical stress causes WBCs to release into the bloodstream to repair micro-tears in muscles.

Heavy exertion can cause white blood cells to release into the bloodstream in massive numbers. If you run a marathon, do a heavy CrossFit session, or engage in powerlifting and then go for a blood draw, you will likely show high WBCs. This is relative leukocytosis combined with a stress response.

Recommendation: Avoid intense exercise for 24 hours before a routine physical or insurance exam. Keep your activity to a light walk.

The Elderly

As we age, our thirst mechanism blunts. We do not feel thirsty even when we need water. Elderly patients often live in a chronic state of mild dehydration. Furthermore, older adults naturally have a lower percentage of total body water compared to younger adults.

For a senior patient, even a small drop in fluid intake can cause rapid hemoconcentration. If you are caring for an elderly patient, do not rely on them to ask for water. Ensure they sip water consistently in the hours leading up to their lab visit.

Pediatric Blood Draws

Children have smaller veins to begin with. The risk of vein collapse is significantly higher. Additionally, a child screaming in fear triggers a potent adrenaline response. This stress response can artificially raise WBCs significantly.

Hydrating a child before a blood draw serves a dual purpose. It prevents dehydration blood test errors, and it makes the veins easier to hit. A single, successful stick reduces pain and tears, which in turn minimizes the stress spike, leading to a more accurate WBC count.

Chronic Kidney Disease & Heart Failure

Some patients are on fluid-restricted diets due to Heart Failure or End-Stage Renal Disease. For these patients, “drinking 64oz of water” is dangerous advice.

If you are on a fluid restriction, do not exceed your doctor’s daily limit. However, save your fluid allowance for the hour before your test. Sip slowly and consistently. Inform the phlebotomist that you are fluid-restricted so they can use a smaller gauge needle (butterfly) to prevent vein collapse without requiring massive hydration.

Patients on Diuretics

If you take medications like Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), Furosemide (Lasix), or Spironolactone, you are chemically dehydrated by design. These drugs force water excretion to lower blood pressure.

For these patients, the dehydration blood test effect is constant. You should speak to your doctor about whether to take your diuretic medication before or after your blood draw. Often, waiting to take the pill until after the test can help preserve enough plasma volume for a successful draw.

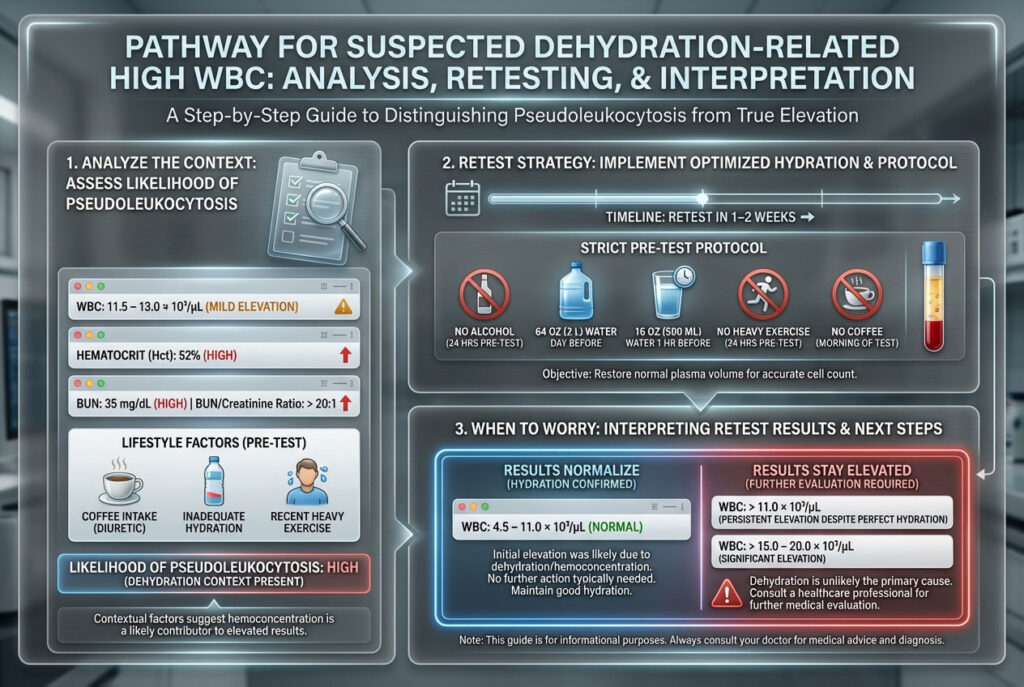

Next Steps: Retesting and Interpretation

So your results came back high. You are worried. You suspect you were dehydrated, but you aren’t sure. What is the logical path forward?

Step 1: Analyze the Context

Look at the full picture.

- Is the WBC count mildly elevated (e.g., 11.5 – 13.0)?

- Is the Hematocrit high?

- Is the BUN high?

- Did you drink coffee before the test?

- Did you fail to hydrate before blood draw?

If the answer to these is “Yes,” the probability of pseudoleukocytosis is high.

Step 2: The Retest Strategy

Do not rush to a hematologist immediately for a mild elevation. Specialized bone marrow biopsies are painful and expensive.

Standard of care often involves a “wait and see” approach. Most primary care physicians will recommend scheduling a repeat CBC in 1 to 2 weeks.

For this retest, you must execute the protocol perfectly to rule out the variable of dehydration.

- No alcohol for 24 hours.

- 64 oz of water the day prior.

- 16 oz of water 1 hour before.

- No heavy exercise.

- No coffee.

Step 3: When to Worry

If you hydrate perfectly, and your WBC count remains persistently elevated, or if it is extremely high (over 15,000 or 20,000), dehydration is likely not the cause. That requires medical investigation into infection, chronic inflammation, autoimmune conditions, or bone marrow disorders.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The question can dehydration cause WBC to be high is answered with a definitive “Yes.” But it is a manageable variable.

You have the power to influence the accuracy of your medical data. By understanding the link between plasma volume and hemoconcentration, you can save yourself from unnecessary anxiety, difficult needle sticks, and expensive follow-up testing.

Your Action Checklist:

- Dehydration concentrates blood. It creates a “false high” or pseudoleukocytosis by reducing the fluid volume in which cells are counted.

- Look for the Triad. A High WBC count accompanied by High Hematocrit and High BUN usually equals Dehydration.

- Drink Up. Aim for 64 oz the day before and 16 oz exactly one hour before your test.

- Veins need water. Hydration prevents vein collapse and hemolysis, protecting the integrity of the sample.

- Retest if unsure. A mild elevation often resolves completely with proper fluids.

- Advocate for yourself. Tell your phlebotomist if you are dehydrated or a hard stick so they can adjust their technique.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can not drinking water cause false high white blood cells?

Yes. Failing to drink water leads to a reduction in plasma volume. This causes hemoconcentration, which artificially increases the density of white blood cells per microliter of blood. This results in a false high reading known as pseudoleukocytosis, where the count is elevated relative to the fluid volume, even if the absolute number of cells in the body is normal.

How much water should I drink before a blood test to avoid errors?

The optimal strategy is to drink approximately 64 ounces (2 liters) of water the day before your test to establish baseline hydration. On the day of the exam, drink 16 ounces (about 500 mL) of plain water exactly one hour before the blood draw. This timing allows the fluid to enter your vascular system, optimizing vein health and blood volume without over-diluting electrolytes.

Will dehydration affect my complete blood count (CBC) results?

Yes. Dehydration affects multiple parameters of a CBC. It typically causes elevated Red Blood Cells (RBC), Hemoglobin, and Hematocrit due to volume loss. It can also cause a false elevation in platelet counts (thrombocytosis) and White Blood Cells (WBC). Conversely, severe dehydration can sometimes mask anemia by making low red blood cell counts appear normal.

What is the difference between infection high WBC and dehydration high WBC?

Infection-induced high WBC (True Leukocytosis) often involves a “Left Shift,” meaning an increase in immature neutrophils (bands), and is usually accompanied by fever, body aches, or localized pain. Dehydration leukocytosis is usually a mild elevation of all cell types due to volume loss, often accompanied by high Hematocrit, high BUN, and physical symptoms like thirst or dark urine.

Is it safe to drink water before a fasting lipid panel?

Yes. Unless your physician has strictly ordered “Nothing by Mouth” (NPO) for a surgical procedure, water is allowed and encouraged for routine fasting blood work like lipid panels, metabolic panels, and glucose tests. Water helps maintain vein patency and makes the blood draw easier and more accurate.

Why do my veins collapse during a blood draw?

Veins collapse when the internal fluid pressure is lower than the vacuum suction of the collection tube. Dehydration lowers your blood volume, reducing venous pressure. When the vacuum tube is engaged, the suction overpowers the vein, causing the walls to flatten and close, stopping blood flow.

Does coffee count as hydration before a blood test?

No. Coffee contains caffeine, which is a mild diuretic. This means it encourages your kidneys to expel water. Drinking strong coffee before a blood test can actually contribute to hemoconcentration rather than fixing it. It can also skew other tests, such as cortisol or glucose. Stick to plain water.

How long does it take for hydration to normalize lab values?

It takes approximately 45 to 60 minutes for ingested water to be absorbed by the gut and enter the vascular system. Drinking water one hour before your test is usually sufficient to restore plasma volume and correct mild dehydration markers. However, chronic dehydration may take 24 hours of consistent fluid intake to fully reverse.

What is pseudoleukocytosis?

Pseudoleukocytosis is a medical term describing a falsely elevated white blood cell count. While it can be caused by lab artifacts (like platelet clumping due to EDTA sensitivity), one of the most common biological causes in healthy patients is hemoconcentration due to dehydration.

Can stress cause high WBC count alongside dehydration?

Yes. “Stress Leukocytosis” occurs when adrenaline causes white blood cells to detach from blood vessel walls (demargination) and enter circulation. If a patient is both dehydrated and afraid of needles, the combination of volume loss and adrenaline can cause a significant, albeit temporary, spike in WBCs.

Should I retest my WBC after hydrating?

If your WBC count was borderline high (e.g., 11,000–13,000/µL) and you suspect you were dehydrated, clinical guidelines often suggest rehydrating and retesting in 1 to 2 weeks. This confirms if the elevation was transient (relative leukocytosis) or persistent.

Does dehydration raise hematocrit and hemoglobin?

Yes. High Hematocrit and Hemoglobin are the hallmark signs of dehydration in blood work. If these are elevated alongside your WBC count, it strongly points to fluid loss as the root cause rather than an infection. This combination is often referred to as the “Dehydration Triad” when combined with elevated BUN.

Disclaimer

The content provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or laboratory results. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read here.

References

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI): Studies on Hemoconcentration and the effects of hydration status on hematological parameters.

- Quest Diagnostics & LabCorp: Patient preparation guidelines regarding fasting and water intake.

- Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM): EFLM Preanalytical Guidelines on venipuncture and patient hydration.

- StatPearls: Clinical review of Leukocytosis and Pseudoleukocytosis.

- American Red Cross: Guidelines on hydration prior to blood donation and phlebotomy.