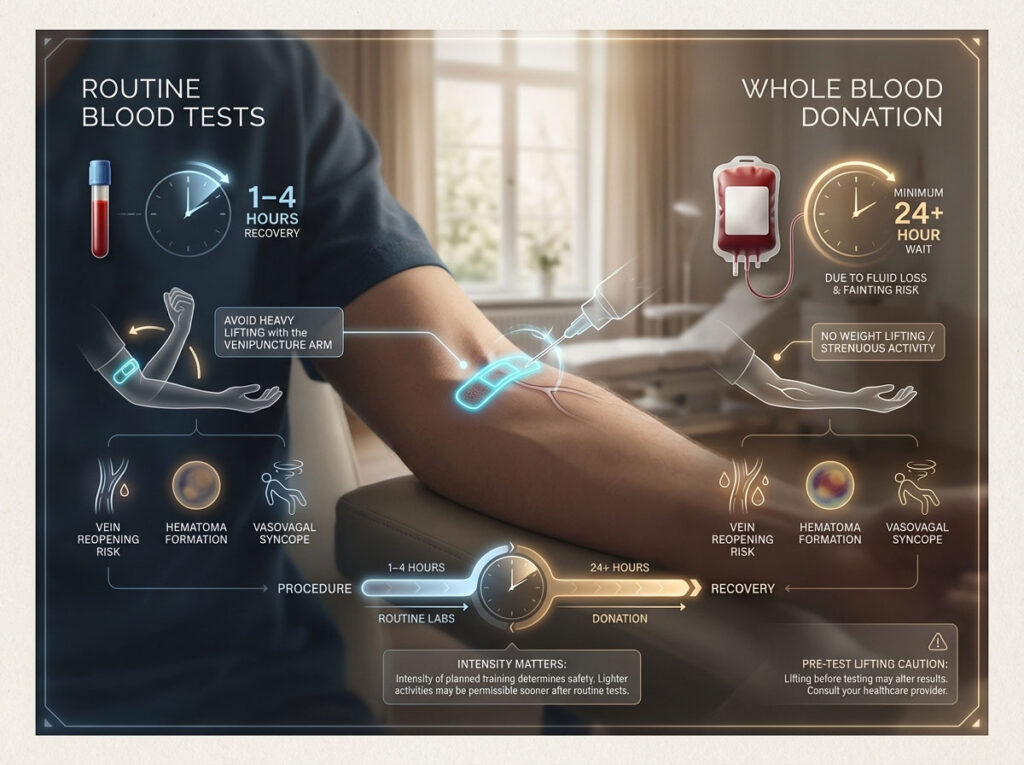

For a routine blood test, it is generally safe to lift weights after 1 to 4 hours, provided you feel well, have eaten, and remain hydrated. However, you must avoid heavy lifting involving the arm used for venipuncture to prevent bruising or a hematoma. In contrast, after a whole blood donation, organizations like the American Red Cross explicitly advise waiting at least 24 hours before performing vigorous exercise or heavy weightlifting to allow fluid replenishment and prevent fainting (vasovagal syncope).

Table of Contents

You have your gym bag packed in the car, your pre-workout mixed, and your training log updated. But you also have an 8:00 AM appointment at the lab for your annual physical. The phlebotomist finds a vein, fills three vials, wraps your arm in a neon bandage, and says the standard line that every lifter dreads. “Take it easy for the rest of the day. No heavy lifting.”

Does “take it easy” mean sitting on the couch and binge-watching television? Or does it just mean skipping the max-effort bench press? Is it acceptable to do a light pump session, or perhaps just some cardio?

For the dedicated lifter, missing a session disrupts momentum. It feels like a step backward. Yet, ignoring medical advice can lead to consequences far more annoying than a missed workout. It can result in a “blown vein,” a hematoma that turns your arm black and blue, or a fainting spell next to the squat rack that leaves you waking up to a circle of concerned gym staff.

The answer to “Can I lift weights after getting blood drawn?” is not a simple binary yes or no. It is a nuanced decision that depends entirely on the volume of blood taken, the specific type of procedure performed, and the intensity of your planned training session.

This comprehensive guide breaks down the physiology of recovery with granular detail. We will cover specific timelines for routine labs versus whole blood donations, the mechanics of why veins reopen under pressure, and the often-overlooked danger of lifting before your test. We will also explore how to modify your training if you absolutely must get back in the gym the same day.

The Physiology of Venipuncture and Exercise

To truly understand the risks of working out after a blood draw, we must look beyond the surface level and understand what happens under the bandage. We need to explore the anatomy of the vein, the physics of blood pressure, and the biological process of healing.

The Mechanics of Venipuncture

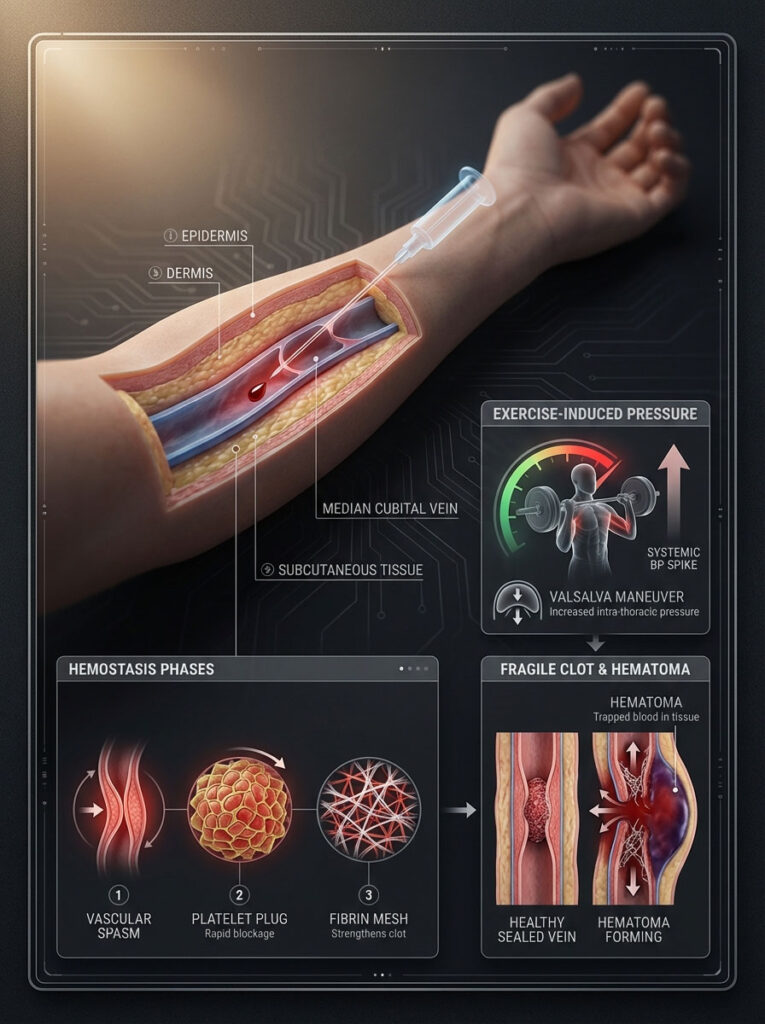

When a phlebotomist inserts a needle for a blood test, they typically target the median cubital vein. This vein is located in the antecubital fossa, the triangular area on the inside of your elbow. It is the preferred site because it is usually large, superficial, and relatively stationary.

However, inserting a needle involves puncturing three distinct layers: the skin (epidermis and dermis), the subcutaneous tissue, and the vein wall itself. This procedure is clinically known as venipuncture.

Once the needle is removed, your body immediately initiates a process called hemostasis. This is the body’s emergency response to stop bleeding. It happens in phases.

- Vascular Spasm: The blood vessel constricts to reduce blood flow.

- Platelet Plug Formation: Platelets rush to the site of the injury and adhere to the collagen fibers in the vessel wall, forming a temporary plug. This is the internal scab.

- Coagulation: Fibrin proteins reinforce the platelet plug, creating a mesh that seals the hole permanently.

While the skin surface might appear healed after a few minutes, the vein wall takes significantly longer to seal completely. This structural weakness is where the conflict with weightlifting begins. The internal seal is fragile for the first few hours.

Clot Formation vs. Systemic Blood Pressure

The primary reason doctors advise you to wait to exercise after a blood test is not usually blood loss. Unless you are donating a pint or more, the volume loss from a routine test is negligible. The real adversary is blood pressure.

When you lift weights, your blood pressure rises significantly. This is a normal physiological response to exertion. It ensures your muscles get enough oxygenated blood. This pressure spike occurs even during exercises that do not directly involve your arms.

During a heavy squat, deadlift, or leg press, you likely perform the Valsalva maneuver. This is the technique of taking a deep breath and bracing your core against a closed glottis to protect your spine. While effective for lifting, it causes a massive spike in intrathoracic and systemic blood pressure. Studies have shown that during a maximal lift, systolic blood pressure can skyrocket to over 300 mmHg.

This pressure is systemic, meaning it travels through your entire vascular system, including the veins in your arms. If the internal clot in your median cubital vein is not fully set, this sudden hydraulic pressure can force it open.

The “Blowout” Risk (Hematoma)

If the internal clot “pops” while you are lifting, blood begins to leak out of the vein. However, because you likely have a bandage or a sealed skin puncture on the surface, the blood has nowhere to go. It gets trapped in the subcutaneous tissue between your skin and muscle.

This results in a hematoma.

A hematoma is different from a regular surface bruise. A bruise is damage to tiny capillaries. A hematoma is a pooling of blood from a larger vessel. It can cause significant swelling, throbbing pain, and a loss of range of motion in the elbow. In severe cases, a large hematoma can compress nearby nerves, leading to numbness or tingling in the forearm and hand.

We have seen frequent instances where athletes ignored the wait time, removed their bandage early, and returned to heavy arm training within an hour. The result is often a swollen, purple, and stiff arm that prevents any upper body training for a full week. Prioritizing vein health over one single workout is the smart play for long-term consistency.

How Long to Wait: The Critical Distinction

Not all blood draws are equal. The recovery time depends heavily on how much blood volume you lost and the purpose of the draw. We must differentiate between a routine diagnostic test, a whole blood donation, and therapeutic procedures.

Routine Blood Tests (The 1-4 Hour Rule)

A standard metabolic panel, cholesterol check, hormone panel, or complete blood count (CBC) usually requires filling 2 to 4 small vials.

This equates to approximately 10 to 20 milliliters (mL) of blood.

For context, the average adult human has about 5,000 mL (5 liters) of blood. Losing 20 mL is physiologically negligible. It represents less than 0.5% of your total blood volume. It will not lower your hemoglobin levels, affect your hydration status, or reduce your oxygen-carrying capacity in any measurable way.

The Protocol:

For a routine blood draw of this size, you should wait 1 to 4 hours before exercising. This window allows the platelet plug to stabilize and the fibrin mesh to form a secure seal on the vein wall.

If you feel fine after 4 hours, you can generally resume your workout. However, it is wise to modify your training to avoid direct strain on the punctured arm. For example, gripping a heavy dumbbell or performing bicep curls puts direct tension on the antecubital fossa and should be avoided for the rest of the day.

Whole Blood Donation (The 24-Hour Rule)

Donating blood is a fundamentally different biological event compared to a routine test. A standard whole blood donation removes about 500 mL (one pint) of blood. This represents roughly 10% of your total blood volume.

The American Red Cross, Vitalant, and the World Health Organization (WHO) are clear and unified on this guidance. You should avoid heavy lifting, vigorous exercise, or strenuous physical labor for at least 24 hours after donating.

The Impact on Performance:

- Fluid Loss: Your plasma volume drops instantly. This leads to acute dehydration and lower blood volume, which means your heart has to beat faster to pump blood to working muscles.

- Oxygen Delivery: You lose a significant amount of red blood cells. Since red blood cells carry oxygen, your VO2 max (aerobic capacity) decreases immediately. It can take 4 to 6 weeks for red blood cell counts to return to pre-donation levels, though performance usually bounces back within a few days as plasma volume restores.

- Fainting Risk: The risk of vasovagal syncope (fainting) is highest within the first 24 hours post-donation if you exert yourself. The combination of reduced blood volume and vasodilation from exercise can cause blood pressure to bottom out, leading to loss of consciousness.

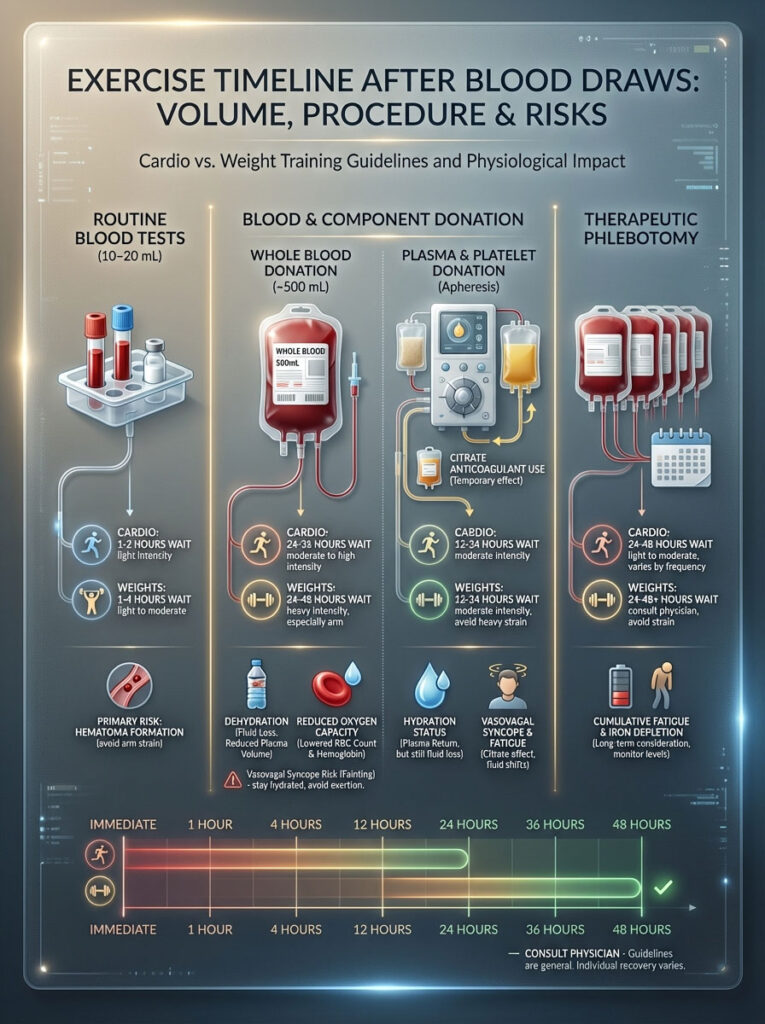

Therapeutic Phlebotomy

Some individuals undergo therapeutic phlebotomy as a medical treatment for conditions like hereditary hemochromatosis (excess iron absorption) or polycythemia vera (excess red blood cell production).

This procedure typically involves removing the same volume as a whole blood donation (450 to 500 mL). However, the context is different. Patients undergoing this treatment often do so on a regular schedule—sometimes weekly or monthly.

While these patients may be accustomed to the procedure, the physiological impact is the same as a donation. The cumulative fatigue can be higher due to the underlying condition. Therefore, the 24-hour rule is strictly enforced for this group. Lifting heavy weights too soon can exacerbate the fatigue associated with the condition and the treatment.

Plasma and Platelet Donation

Apheresis is the process of donating only specific components of the blood, such as plasma or platelets, while returning the red blood cells to the donor.

- Plasma Donation: Because your red blood cells are returned, your oxygen capacity remains largely intact. However, you still lose a significant amount of fluid and electrolytes. Dehydration is the main risk.

- Platelet Donation: This takes longer than a whole blood donation and often involves a needle in both arms. The recovery focuses on the vein sites and hydration.

The Protocol:

For plasma or platelet donation, the cardiovascular recovery is faster than whole blood donation, usually 12 to 24 hours. However, because the procedure takes longer and may involve anticoagulants (citrate) used during the machine separation process, you should still avoid heavy lifting for at least 12 to 24 hours to prevent bruising and calcium depletion.

Comparison of Recovery Timelines

Below is a detailed breakdown of wait times based on the procedure type to help you plan your training week.

| Type of Procedure | Volume Drawn | Primary Risk | Wait Time (Cardio) | Wait Time (Weights) |

| Routine Lab Test | Small (~10–20 mL) | Hematoma (Bruising) | Immediate (Light) | 1–4 Hours |

| Fasting Blood Test | Small (~10–20 mL) | Syncope (Fainting) | After Eating | After Eating + 2 Hours |

| Whole Blood Donation | Large (~500 mL) | Dehydration / Fainting | 24 Hours | 24–48 Hours |

| Plasma Donation | Variable (Fluids returned) | Dehydration | 6–12 Hours | 12–24 Hours |

| Therapeutic Phlebotomy | Large (~500 mL) | Fatigue / Fainting | 24 Hours | 24–48 Hours |

Why You Should Skip the Gym Before Your Appointment

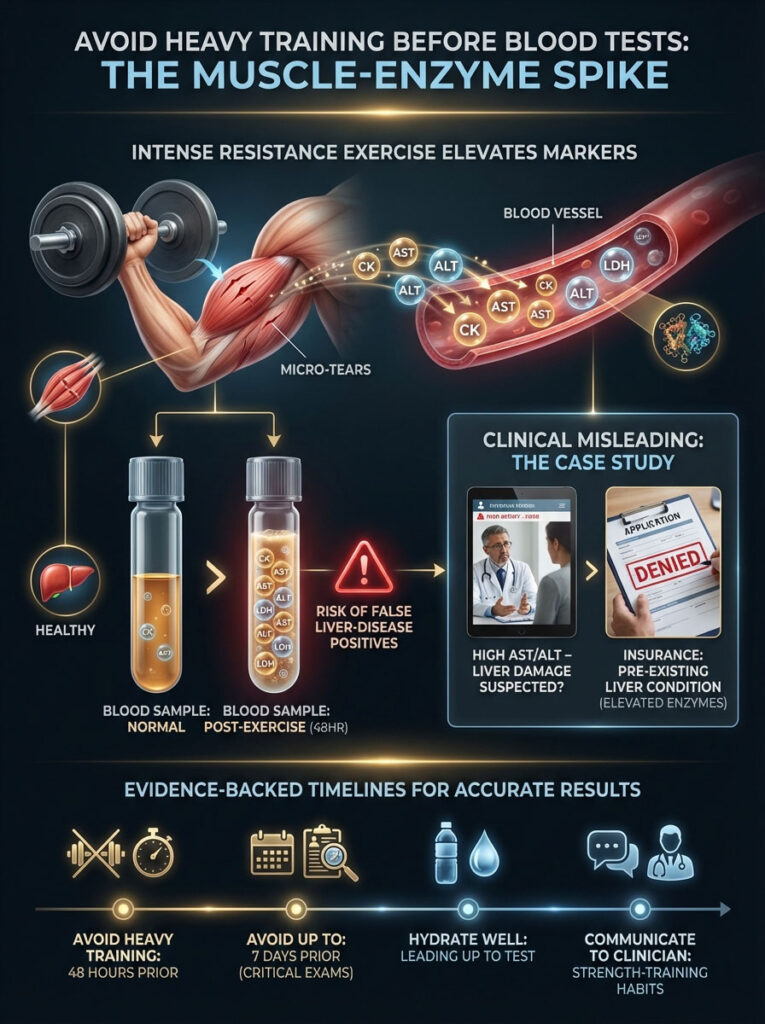

Most people ask about working out after a blood test. They view the test as the finish line. However, the real danger to your medical records and your peace of mind comes from lifting weights before your appointment.

Intense exercise can dramatically skew your lab results. This can lead to false diagnoses, additional expensive testing, and unnecessary medical anxiety.

The False Positive Liver Scare

When you lift heavy weights, especially during eccentric movements (the lowering phase of a lift), you create microscopic tears in your muscle fibers. This micro-trauma is a normal, necessary part of hypertrophy (muscle growth) and strength adaptation.

As these muscle fibers repair themselves, they leak certain intracellular proteins and enzymes into your bloodstream. The most notable markers are:

- Creatine Kinase (CK): A primary marker of muscle damage.

- Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST): An enzyme found in the liver but also in skeletal muscle.

- Alanine Transaminase (ALT): An enzyme found in the liver and muscle.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): A general marker of tissue damage.

The problem arises because doctors use AST and ALT primarily to screen for liver damage, hepatitis, and other hepatic diseases. They often do not realize that these enzymes are also abundant in muscle tissue.

The Research on False Positives

Studies published in journals such as the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research have documented this phenomenon extensively. They have shown that a heavy lower-body weight training session can elevate AST and ALT levels by 300% or more. These levels can remain elevated for up to 7 days post-exercise, though they typically peak around 24 to 48 hours.

If your doctor sees these numbers without knowing you squatted 400 pounds yesterday, they will not think “this patient is strong.” They will think “this patient has liver cell death.”

The Scenario:

Consider the case of a natural bodybuilder or powerlifter applying for life insurance. They train legs heavily on Monday. On Tuesday morning, they go in for their insurance paramedical exam. The results come back on Friday showing AST and ALT levels three times the upper limit of normal. The underwriter flags them as high-risk for liver disease or alcohol abuse. Their application is denied or their premium is tripled.

This is a common administrative nightmare for strength athletes. It forces them to undergo re-testing after a week of total rest to prove their liver is healthy.

Actionable Advice:

If you have a metabolic panel, life insurance exam, or liver enzyme test scheduled:

- The 48-Hour Rule: Avoid heavy strength training, CrossFit, or high-intensity interval training for at least 48 hours prior to the blood draw.

- The 7-Day Rule: If you are prone to high enzyme spikes or train with extreme volume, consider a full deload week before an important insurance exam.

- Hydrate: Ensure you are well-hydrated to keep other markers like BUN and Creatinine within range.

- Communicate: Tell your doctor: “I engage in heavy resistance training which may elevate my muscle enzymes.”

Modifying Your Training Schedule

If you are determined to workout after blood test procedures, you must modify your session to ensure safety. You cannot simply jump back into your peaking program or hit a One Rep Max (1RM) attempt.

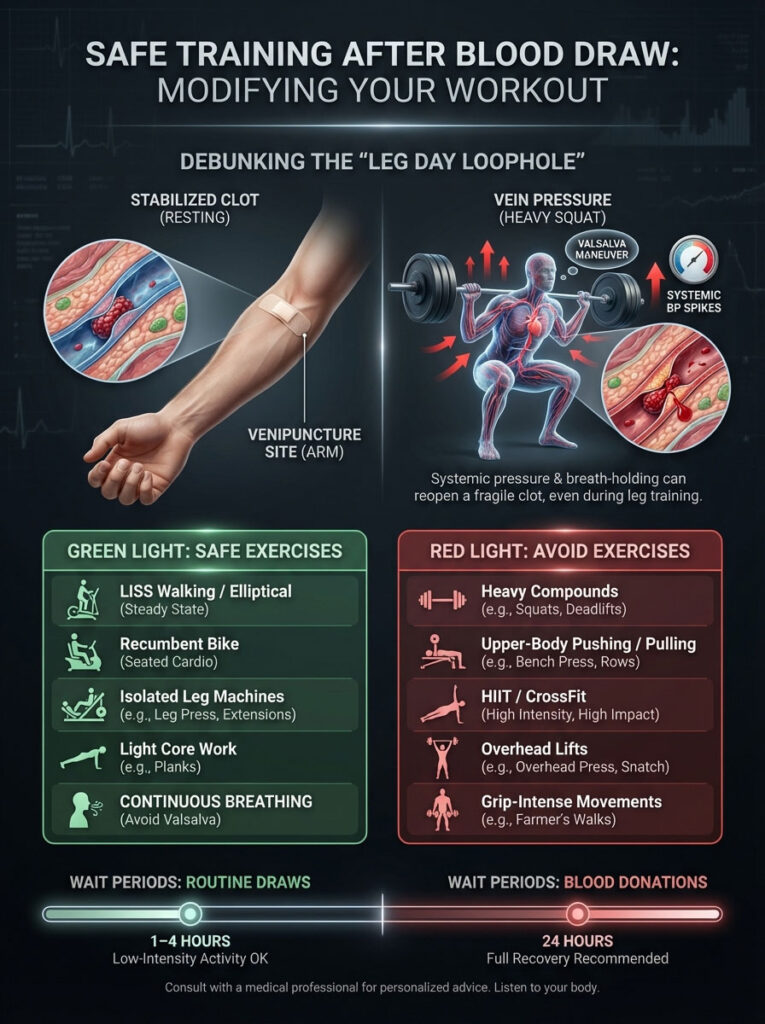

The “Leg Day Loophole” Myth

A frequent question in fitness forums is: “Can I do leg day if my blood was drawn from my arm?”

The logic seems sound at first glance. You are not using your arms to squat or leg press. The bandage is nowhere near the moving weights.

However, we must return to the concept of systemic blood pressure and the Valsalva maneuver.

Compound leg movements require massive core bracing. When you unrack a heavy barbell for a squat, you take a deep breath into your diaphragm and clamp your abs down. This increases intra-abdominal pressure to support the spine.

This pressure does not stay in the abdomen. It radiates outward to the peripheral vasculature. Watch a powerlifter squat; the veins in their neck, forehead, and arms bulge visibly. This is due to the back-pressure preventing venous return to the heart.

If that vein in your arm has a fresh, fragile clot, this surge in venous pressure can easily force the clot open from the inside.

The Verdict: Heavy squats, deadlifts, and barbell lunges are risky immediately after a blood draw. The systemic pressure is too high.

Safe Exercises (Green Light)

If you wait the recommended 1 to 4 hours after a routine draw, these exercises are generally safe because they allow you to breathe continuously and do not require extreme bracing:

- Walking or Elliptical: Low intensity steady state (LISS) cardio keeps blood pressure manageable and promotes circulation without spikes.

- Recumbent Bike: This is an excellent option as it minimizes orthostatic hypotension (dizziness upon standing) and requires zero arm involvement.

- Isolation Machines: Leg extensions, lying leg curls, seated calf raises, or hip adductor/abductor machines. These exercises isolate specific muscles and generally require less systemic bracing than free weights.

- Core Work: Basic planks or crunches, provided you do not hold your breath.

Risky Exercises (Red Light)

Avoid these movements for at least 6 to 12 hours after a routine draw, and 24 hours after a donation:

- Heavy Compound Lifts: Squats, deadlifts, leg press, barbell rows.

- Upper Body Pushing/Pulling: Bench press, overhead press, chin-ups, lat pulldowns. These exercises put direct tension on the biceps and triceps, which compresses the veins in the arm.

- HIIT / CrossFit: The rapid changes in posture (burpees, box jumps) and heart rate increase the risk of fainting and dislodging the clot.

- Overhead Movements: Holding weights overhead drains blood from the arm initially but causes a rush of pressure when lowered.

- Grip Heavy Work: Farmer’s walks or heavy shrugs require intense forearm contraction, which squeezes the veins near the puncture site.

Recognizing and Treating Complications

Despite our best intentions, complications can happen. Sometimes a vein is fragile, or a movement was more intense than expected. Knowing how to react to symptoms can save you from a medical emergency or a long-term injury.

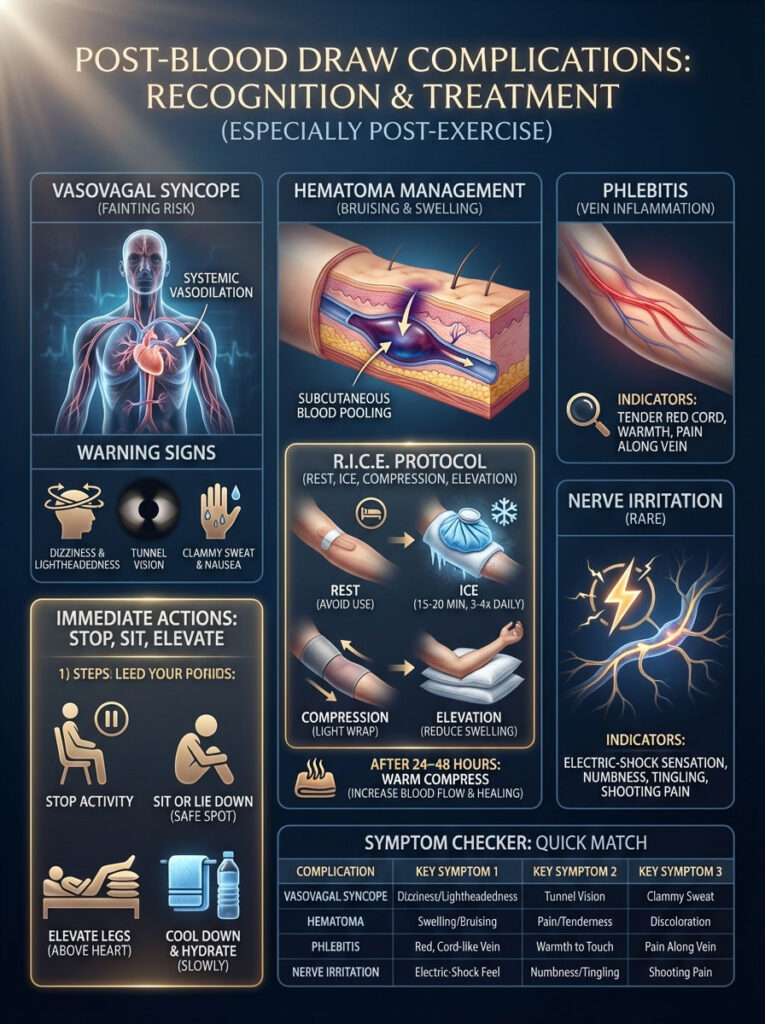

Vasovagal Syncope (Fainting)

This is the most common adverse reaction to blood draws and donations. It is a reflex of the involuntary nervous system that causes the heart to slow down (bradycardia) and blood vessels in the legs to widen (vasodilation). This causes blood to pool in the legs and lowers blood flow to the brain.

The trigger is often a “perfect storm” of three factors: fasting (low blood sugar), dehydration (low blood volume), and exercise (diversion of blood to muscles).

Warning Signs:

- Sudden lightheadedness or dizziness.

- Tunnel vision or seeing spots.

- A sudden feeling of warmth or a cold, clammy sweat.

- Nausea or a “sinking” feeling in the stomach.

- Pale skin.

Immediate Action:

If you feel this at the gym, stop immediately. Do not try to “push through” or finish your set.

- Sit or Lie Down: Get close to the ground to prevent injury from falling.

- Elevate Legs: If possible, prop your feet up on a bench. This uses gravity to help blood return to the brain.

- Cool Down: Remove excess clothing or put a cool towel on your neck.

- Hydrate: Drink water or an electrolyte beverage slowly.

Managing a Hematoma (Blowout)

If you notice your arm swelling, getting tight, or discoloring during or after your workout, you likely have a hematoma. This means the vein is leaking under the skin.

The Protocol (R.I.C.E.):

- Rest: Stop using the arm immediately. Do not test it to see if it “still hurts.”

- Ice: Apply a cold pack (wrapped in a cloth to prevent ice burn) for 15 to 20 minutes. This constricts the blood vessels and slows the internal bleeding. Repeat this every hour for the first few hours.

- Compression: Re-apply a pressure bandage if possible, or wrap the area firmly (but not too tightly) with an elastic bandage.

- Elevation: Keep the arm raised above heart level to reduce swelling.

After the first 24 to 48 hours, once the bleeding has stopped, you can switch to warm compresses to help the body absorb the trapped blood. Note that a large hematoma can take 2 to 3 weeks to fade completely and may turn various shades of yellow and green.

Phlebitis and Nerve Irritation

In rare cases, the vein can become inflamed. This is called phlebitis. It presents as a tender, red cord under the skin that feels warm to the touch.

Another complication is nerve irritation. The median cubital vein sits close to cutaneous nerves. If you feel a sharp, “electric shock” sensation radiating down your forearm or into your hand while lifting, you may be compressing a nerve that was irritated by the needle.

If you suspect phlebitis or experience persistent nerve pain, numbness, or loss of grip strength, seek medical attention.

Symptom Checker Table

Use this table to determine if your post-gym symptoms are normal or require action.

| Symptom | Normal Reaction? | Action Required | Can I Continue Workout? |

| Slight soreness at site | Yes | None | Yes (Modify intensity) |

| Small bruise (< dime size) | Yes | Monitor | Yes (Avoid direct strain) |

| Sudden throbbing/heat | No | Apply Pressure | NO – Stop Immediately |

| Large lump (Hematoma) | No | Ice & Compress | NO – Go Home |

| Dizziness / Tunnel Vision | No | Lie down, Elevate feet | NO – Hydrate & Eat |

| Radiating nerve pain | No | See Doctor | NO |

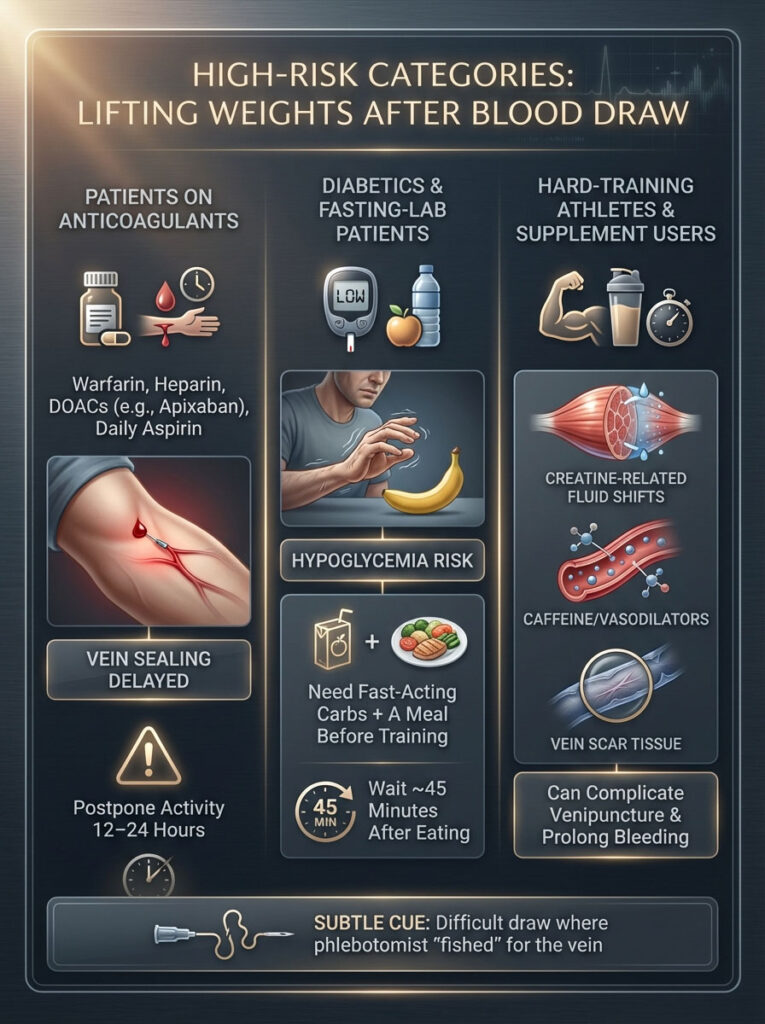

Are You in a High-Risk Category?

Certain individuals need to be extra cautious when planning to lift weights after blood draw procedures. Your medical history and age play a significant role in how fast your veins seal.

Patients on Anticoagulants

If you take blood thinners for heart conditions, deep vein thrombosis, or post-surgery recovery, your clotting cascade is chemically inhibited. Common medications include:

- Warfarin (Coumadin)

- Heparin

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) like Eliquis or Xarelto.

- Daily Aspirin therapy.

For this group, the “1 to 4 hour” rule for routine labs does not apply. Even a small puncture can bleed for a long time.

Guideline: You should wait at least 12 to 24 hours before engaging in any activity that could bruise the arm or raise blood pressure significantly. The risk of a massive hematoma is much higher because the internal seal takes much longer to form and is more fragile.

Diabetics and Fasting Labs

Many blood tests, particularly for glucose and lipid panels, require fasting for 8 to 12 hours. This usually means skipping breakfast and relying on water.

If you go straight to the gym after your blood draw without eating, you are training in a fasted, depleted state. You risk hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

Hypoglycemia combined with the minor fluid loss from the draw creates a high risk for passing out. Symptoms include shakiness, confusion, rapid heartbeat, and extreme fatigue.

Strategy: Bring a fast-acting carbohydrate source (like fruit, juice, or glucose tabs) and a solid meal to eat immediately after your appointment. Do not train until you have stabilized your blood sugar and waited roughly 45 minutes for digestion to begin.

Hard-Training Athletes and Supplement Users

Athletes who use supplements like creatine, pre-workout stimulants, or vasodilators (pump products) need to be aware of how these affect venipuncture.

Creatine: While safe and effective for performance, creatine draws water into the muscle cells. If you are not drinking extra water, your intravascular volume (blood in the veins) might be lower, making veins harder to access.

Pre-Workout (Caffeine): Caffeine is a vasoconstrictor initially, but pump ingredients like Citrulline Malate cause vasodilation. This can increase bleeding time after the needle is removed.

Scar Tissue: If you have had blood drawn frequently from the same spot, or if you have a history of difficult draws, you may have scar tissue on the vein. This makes the vein walls stiffer and potentially slower to seal.

If you experienced a difficult draw where the phlebotomist had to “fish” for the vein or stick you multiple times, extend your rest period. The trauma to the area is greater than a clean, single-stick draw.

Nutrition and Hydration for Recovery

Recovery is not just about time; it is about resources. You cannot lift weights effectively or heal your vein if your fluid balance and nutrient levels are off.

The Fluid Replacement Rule

After any blood draw, your immediate priority is hydration. Blood is largely water.

Aim to drink 16 to 24 ounces of water immediately after your appointment.

If you donated blood, this is non-negotiable. You need to replace the plasma volume to restore blood pressure. Avoid alcohol for at least 24 hours post-donation. Alcohol is a diuretic (causes water loss) and also dilates blood vessels, which can restart bleeding at the puncture site.

Electrolytes and Iron

For blood donors, iron replenishment is key to long-term performance and energy. Hemoglobin contains iron, and when you donate red blood cells, you lose a significant store of iron.

It takes weeks to fully replace the red blood cells lost in a donation. To support this process, consume iron-rich foods:

- Heme Iron (Animal source): Red meat, poultry, fish. This is absorbed most efficiently.

- Non-Heme Iron (Plant source): Spinach, lentils, fortified cereals, beans.

Pro Tip: Pair iron-rich foods with Vitamin C (like orange juice, bell peppers, or strawberries) to enhance iron absorption. Avoid drinking coffee, tea, or milk with your iron-rich meal, as calcium and tannins can block iron absorption.

Post-Fasting Protocol

If you fasted for your test, do not attempt to lift weights on an empty stomach.

Your body is in a catabolic (breakdown) state. Training in this state usually leads to poor performance, lower energy, and increased cortisol levels.

Consume a balanced meal of complex carbohydrates (oats, rice, whole grains) and lean protein (eggs, whey, chicken). Wait roughly 45 to 60 minutes after eating before hitting the gym floor. This replenishes your glycogen stores and provides amino acids for recovery.

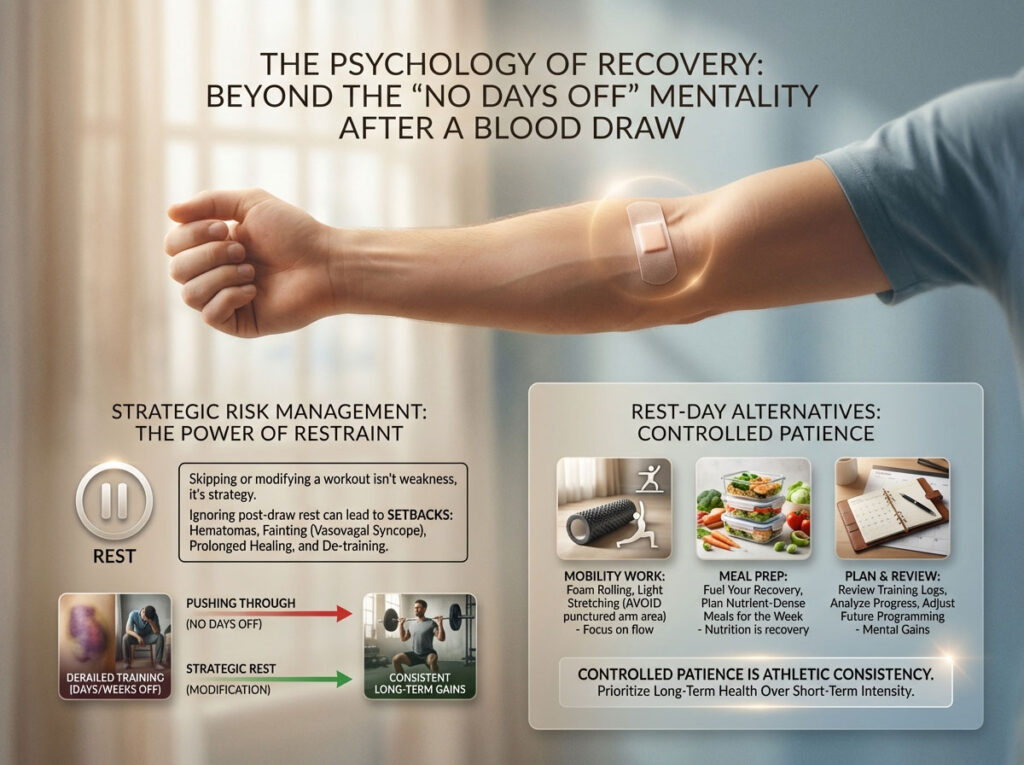

Psychological Considerations: The “No Days Off” Mentality

It is important to address the psychology of the dedicated athlete. In modern fitness culture, there is often a “no days off” mentality. We fear that missing one session will ruin our progress or that we are being “lazy.”

This mindset can be dangerous in a medical context.

Taking a rest day or a light active recovery day after a blood draw is not laziness; it is risk management. It is a strategic decision to protect your body so you can train harder tomorrow. A blown vein or a fainting episode is a setback that lasts days or weeks. A rest day lasts 24 hours.

If you feel anxious about missing a workout, use the time for other productive fitness activities that don’t risk your health:

- Mobility Work: Foam rolling and stretching (avoiding the arm).

- Meal Prep: Cook your meals for the week.

- Program Planning: Review your training log and plan your next block.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Balancing your fitness goals with your health needs does not have to be complicated. The question “How long to wait to exercise after blood test?” has a nuanced answer, but the rules of thumb are clear and actionable.

- Routine Labs (Small Volume): You are generally safe to lift after 4 hours. Start with light weights, listen to your body, and avoid direct arm strain or heavy gripping.

- Blood Donation (Large Volume): Respect the physiology. Wait a full 24 hours before heavy lifting or high-intensity cardio. Your blood volume and oxygen capacity need time to reset.

- Pre-Test Warning: Do not lift heavy for 48 hours before a liver enzyme test. This prevents false positive diagnoses of liver damage caused by muscle micro-trauma.

- The “Leg Day” Myth: Do not assume leg day is safe immediately after a draw. Systemic blood pressure spikes from squatting can blow out an arm vein.

- Listen to Your Veins: If it throbs, stop. If you feel dizzy, sit down. A missed workout is better than a medical emergency.

Your gains will still be there tomorrow. Give your body the brief time it needs to heal the vessel, and you will be back to 100% without the bruised arm to show for it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Can I lift weights 1 hour after a blood test?

It is risky. While you likely won’t faint from a small routine blood draw, lifting heavy weights within an hour can dislodge the fresh clot in your vein. This causes re-bleeding and a hematoma (a painful collection of blood under the skin). It is much safer to wait at least 4 hours for the vein to seal properly.

Can I do cardio after getting blood drawn?

Yes, light cardio such as walking, riding a stationary bike, or using an elliptical machine is generally safe immediately after a routine blood draw. These activities do not spike blood pressure as drastically as heavy lifting. However, you should avoid high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or sprinting for a few hours to prevent pressure spikes.

Why does my arm hurt after lifting weights following a blood test?

Pain usually indicates a hematoma or bruised muscle. The strain of lifting likely caused a small amount of internal bleeding at the puncture site, even if you didn’t see blood on the bandage. You should stop lifting immediately, apply ice to the area, and rest the arm for the remainder of the day.

How long should I wait to lift weights after donating blood?

You should wait strictly 24 hours. Donating a pint of blood significantly lowers your plasma volume (causing dehydration) and red blood cell count (lowering oxygen capacity). Lifting heavy weights too soon increases the risk of fainting, dizziness, and injury due to fatigue.

Does donating plasma affect muscle growth?

Donating plasma temporarily removes protein and hydration but does not permanently ruin muscle growth. The body replenishes plasma proteins relatively quickly. However, the acute dehydration can ruin your immediate workout performance and recovery. It is best to wait 12 to 24 hours and hydrate aggressively before training hard.

Is it safe to exercise after fasting blood work?

Only after you eat and hydrate. Exercising while fasting and after the minor fluid loss of a blood draw drastically increases the risk of passing out (vasovagal syncope). You are operating on low blood sugar and low fluid volume. Eat a meal with complex carbs and protein before going to the gym.

Can I do a bicep workout after a blood draw?

You should avoid direct bicep work on the affected arm for at least 12 hours. The median cubital vein, where blood is usually drawn, sits directly over the bicep tendon. The contraction of the bicep muscle puts direct mechanical pressure and stretch on the vein, which can reopen the puncture site.

What happens if you work out too hard after giving blood?

You risk dizziness, nausea, fainting, and injury. Because your body has less oxygen-carrying capacity (fewer red blood cells), your heart rate will spike higher than normal for the same effort level. Your body simply cannot cool itself or fuel the muscles as efficiently as usual.

Can I take pre-workout after a blood test?

Yes, but use caution. If you fasted for the test, taking high-caffeine formulas on an empty stomach can increase jitteriness, anxiety, and heart rate. This can mask the signs of fatigue or hypoglycemia. Ensure you have eaten a solid meal and hydrated with water before taking stimulants.

Can I swim after a blood draw?

You should wait until the puncture site is fully scabbed over and sealed, which usually takes 4 to 6 hours. This is to prevent infection from bacteria in the pool water entering the wound. If you have a waterproof bandage, you may be able to swim sooner, but avoid vigorous strokes that stretch the arm.

Will lifting weights affect my blood test results?

Yes. Heavy weightlifting causes muscle breakdown, which spikes markers like AST, ALT, and Creatine Kinase (CK) in your blood. This can lead doctors to misdiagnose you with liver issues or tissue damage. To ensure accurate results, avoid heavy lifting for 48 hours before your blood test.

How do I treat a bruise from a blood draw?

Use the R.I.C.E. method: Rest the arm, Ice the area for 15 minutes every hour (wrapped in a cloth), Compress with a bandage if comfortable, and Elevate the arm above heart level. This reduces swelling and pain. If the bruise spreads significantly or becomes hot, see a doctor.

Disclaimer: The content provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with your physician, phlebotomist, or a qualified healthcare provider regarding specific medical conditions or instructions following a medical procedure. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References:

- American Red Cross. “What to Do After Donating Blood.” redcrossblood.org

- Pettersson, J., et al. “Muscular exercise can cause highly pathological liver function tests in healthy men.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center. “Patient Education: Post-Phlebotomy Care.”

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Blood Donor Selection: Guidelines on Assessing Donor Suitability for Blood Donation.”

- Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. “Effect of resistance training on liver function tests.”