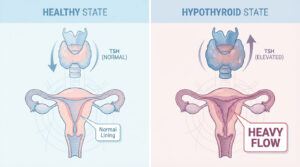

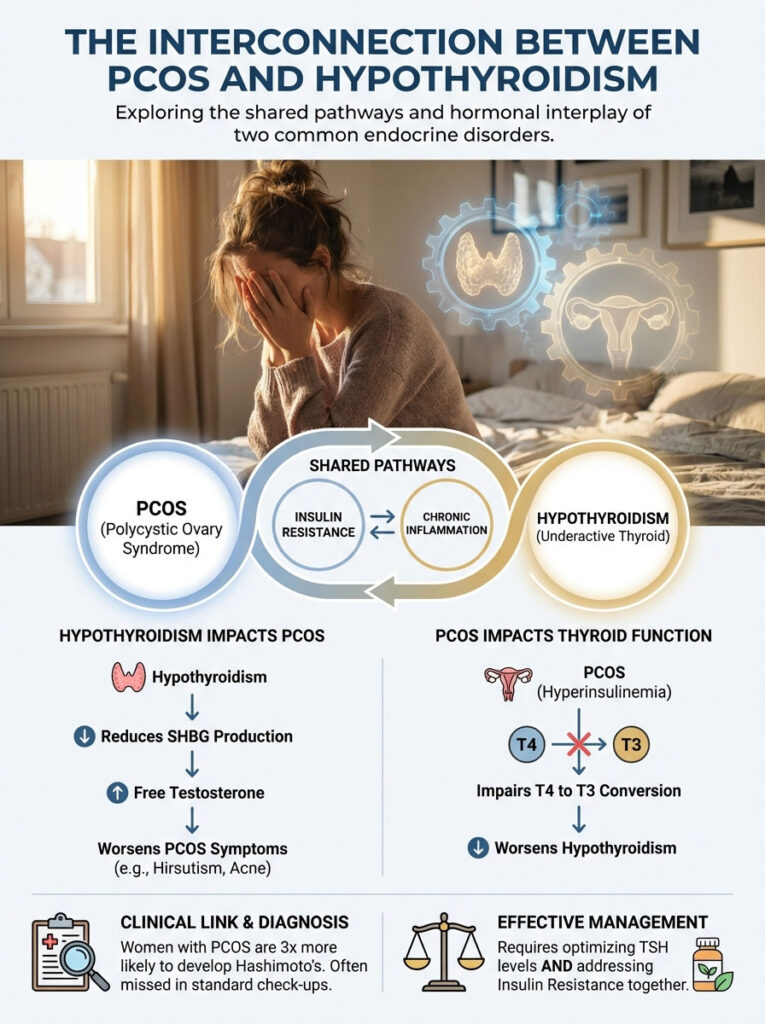

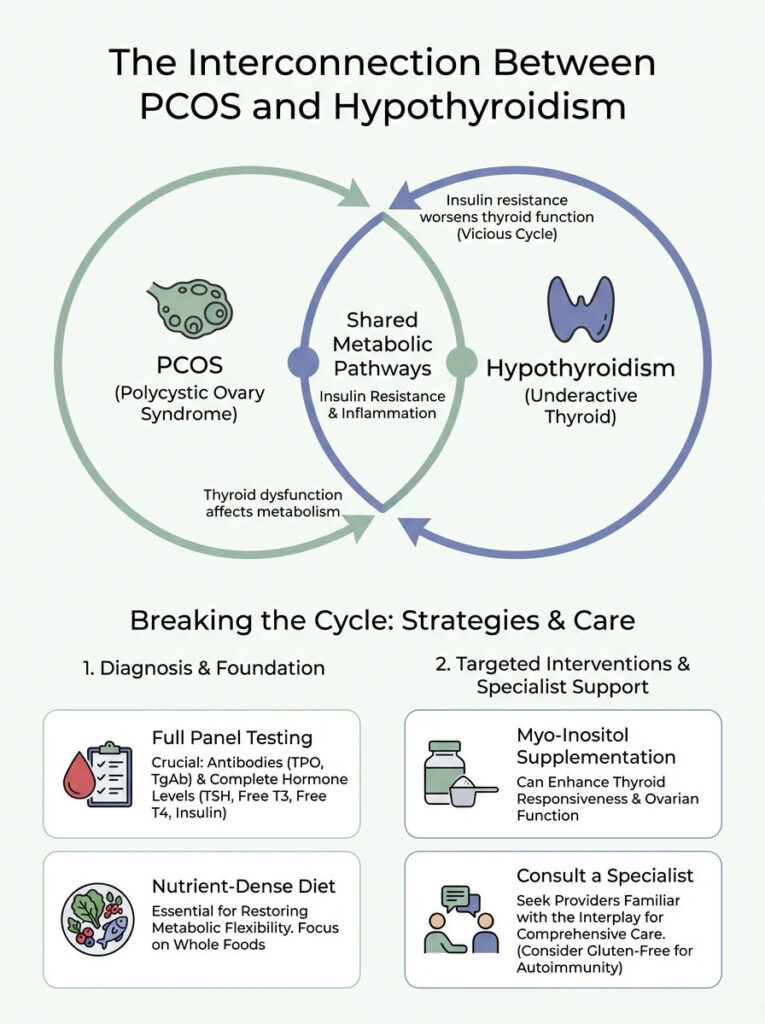

PCOS and hypothyroidism are distinct but deeply interconnected endocrine disorders that often coexist due to shared pathways involving insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and autoimmunity. The link is primarily driven by Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). Hypothyroidism reduces SHBG production in the liver. This reduction increases free testosterone levels. Consequently, patients experience worsened PCOS symptoms like hirsutism and acne.

Table of Contents

Conversely, the hyperinsulinemia associated with PCOS can impair the conversion of T4 to active T3 thyroid hormone. Effective management requires a dual-targeted approach. You must optimize TSH levels (ideally below 2.5 mIU/L) with medication while simultaneously treating insulin resistance through metformin, myo-inositol, and an anti-inflammatory diet.

You are doing everything right. You track your calories meticulously. You prioritize eight hours of sleep. You take your supplements every morning. Yet, the scale refuses to budge. Your energy crashes by 2 PM. Your cycle remains unpredictable.

For many women, this isn’t just “bad luck.” It is not a lack of discipline. It is the result of a complex metabolic collision between PCOS and hypothyroidism.

In clinical practice, we rarely see these two conditions exist in isolation. They feed off one another. If you have Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), you are statistically three times more likely to develop Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than women without it. This is not a coincidence.

It is a biochemical cross-talk between your ovaries and your thyroid gland. Unfortunately, most standard check-ups miss this connection completely. You might see a gynecologist for your periods and a separate doctor for your thyroid. They rarely compare notes.

This article moves beyond generic advice. We will examine the specific physiological mechanisms that link these glands. We will explore why standard lab ranges often fail you. Finally, we will detail the integrative protocols required to treat this “double hit” to your endocrine system.

Key Statistics: The Endocrine Overlap

- 25% to 30% of women with PCOS have elevated Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO) antibodies. This indicates active autoimmunity.

- TSH > 2.5 mIU/L is associated with increased miscarriage risk and lower ovulation rates in PCOS patients.

- 45% of hypothyroid patients demonstrate polycystic ovarian morphology on ultrasound even without the full syndrome.

- Insulin Resistance is present in approximately 70% of PCOS cases and 50% of hypothyroid cases.

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism (TSH 4.5–10 mIU/L) is found in roughly 15% of the PCOS population.

The Pathophysiology of PCOS and Hypothyroidism

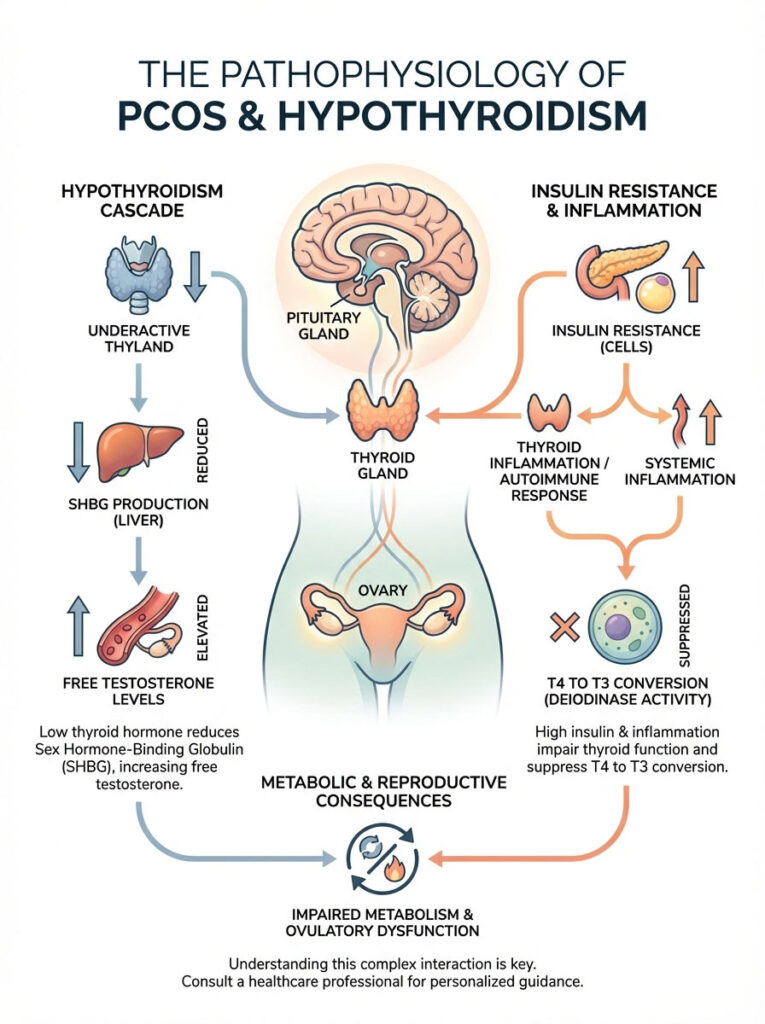

To manage your health, you must understand the machinery. The body does not have a separate “thyroid department” and “ovary department.” They are part of the same corporate structure. They communicate through the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axes.

When one axis malfunctions, it sends ripple effects to the other. Understanding these mechanisms empowers you to ask for the right tests.

The SHBG Mechanism: The “Sponge” Effect

This is perhaps the most critical concept to grasp regarding PCOS and hypothyroidism. Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) is a protein produced by the liver. Think of SHBG as a sponge.

This sponge soaks up excess sex hormones. It specifically binds to testosterone and estrogen. When bound, these hormones are inactive. They cannot cause symptoms.

Thyroid hormone is a primary stimulator of SHBG production. When you have hypothyroidism, your liver produces less SHBG. You lose your “sponges.”

With less SHBG available, more testosterone remains “free” in your bloodstream. It becomes active. This leads to the high Free Androgen Index (FAI) seen in PCOS. The result is cystic acne, male-pattern hair growth (hirsutism), and hair loss.

Treating the thyroid often raises SHBG levels. This naturally lowers free testosterone. Therefore, treating the thyroid is often the first step in fixing the ovaries.

Insulin Resistance as the Bridge

Insulin resistance is the hallmark of classic PCOS. When your cells stop responding to insulin, your pancreas pumps out more to compensate. This state is called hyperinsulinemia.

High insulin damages the thyroid gland in two distinct ways. First, it promotes nodule formation. Insulin acts as a growth factor. High circulating insulin stimulates the thyroid tissue. This leads to increased thyroid volume and the formation of nodules or goiter.

Second, it triggers autoimmunity. Chronic insulin spikes create systemic inflammation. This disturbs the immune system. It can potentially trigger the autoimmune attack seen in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

The relationship works in reverse as well. Thyroid hormones modulate glucose metabolism. When you are hypothyroid, glucose absorption in the gut slows down. However, cellular glucose uptake also slows down. The result is a sluggish metabolism that breeds further insulin resistance.

The T4 to T3 Conversion Issue

Your thyroid gland primarily produces T4 (Thyroxine). T4 is relatively inactive. It is a storage hormone. It must be converted into T3 (Triiodothyronine) to work.

T3 is the active hormone that powers your metabolism. This conversion happens in the liver and gut. It relies on an enzyme called deiodinase.

Here is the problem. The systemic inflammation caused by PCOS suppresses deiodinase activity. You might have plenty of T4. Your standard labs might look fine. But you aren’t converting it to T3.

This results in “cellular hypothyroidism.” Your blood tests look passable. Yet, you feel exhausted, cold, and unable to lose weight. This conversion block is a major reason why women with PCOS often feel worse even when their TSH is “normal.”

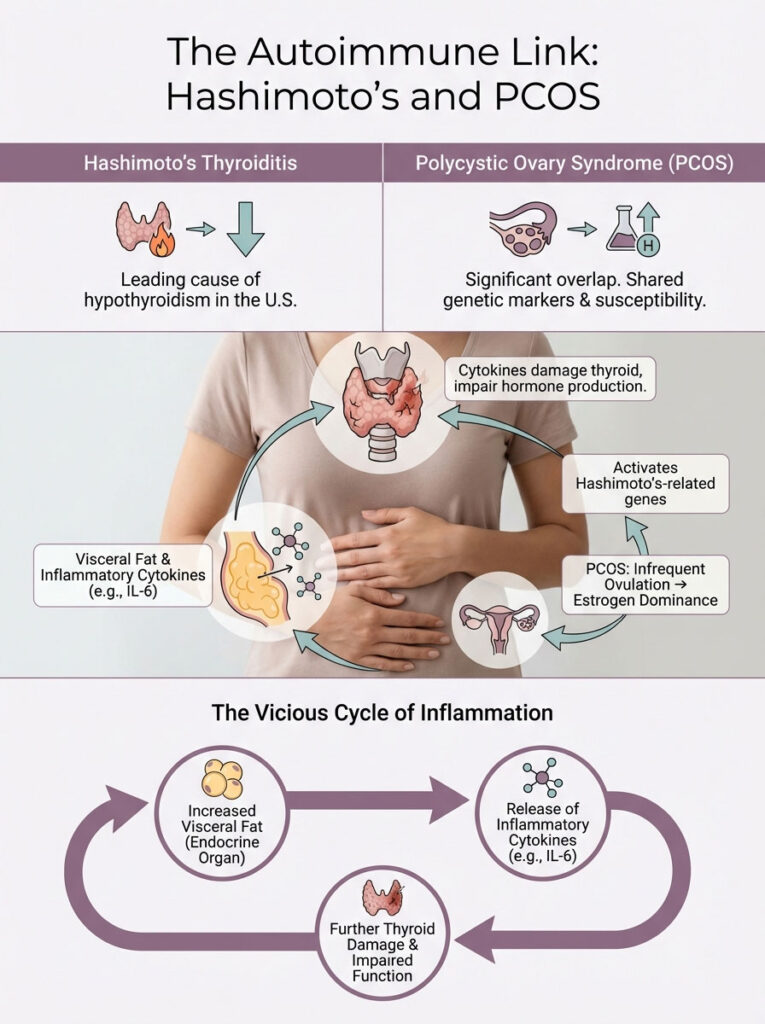

The Autoimmune Link: Hashimoto’s and PCOS

The majority of hypothyroidism cases in the United States are caused by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. This is an autoimmune condition. The overlap with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is undeniable.

It is not just about hormones. It is about the immune system losing its tolerance.

Genetic Predisposition and Estrogen Dominance

Research suggests a shared genetic susceptibility. Both autoimmune diseases and PCOS share common genetic markers. Specifically, polymorphisms in the genes regulating the immune system (like CTLA-4) are found in both patient groups.

Furthermore, PCOS is characterized by “unopposed estrogen.” Because ovulation is infrequent, the body lacks progesterone. Progesterone is the hormone that balances estrogen.

Estrogen is immune-stimulatory. High levels of estrogen can enhance the activity of B-cells. B-cells are responsible for producing antibodies. This estrogen dominance can essentially “turn on” the genes for Hashimoto’s.

Systemic Inflammation and Cytokines

Visceral adipose tissue (belly fat) is common in PCOS due to insulin issues. This fat is not just stored energy. It is an active endocrine organ.

This tissue releases inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines travel through the bloodstream. They attack the thyroid gland. They impair its ability to produce hormones.

This creates a cycle of destruction. The inflammation from PCOS damages the thyroid. The damaged thyroid slows metabolism. The slow metabolism increases visceral fat. The fat creates more inflammation.

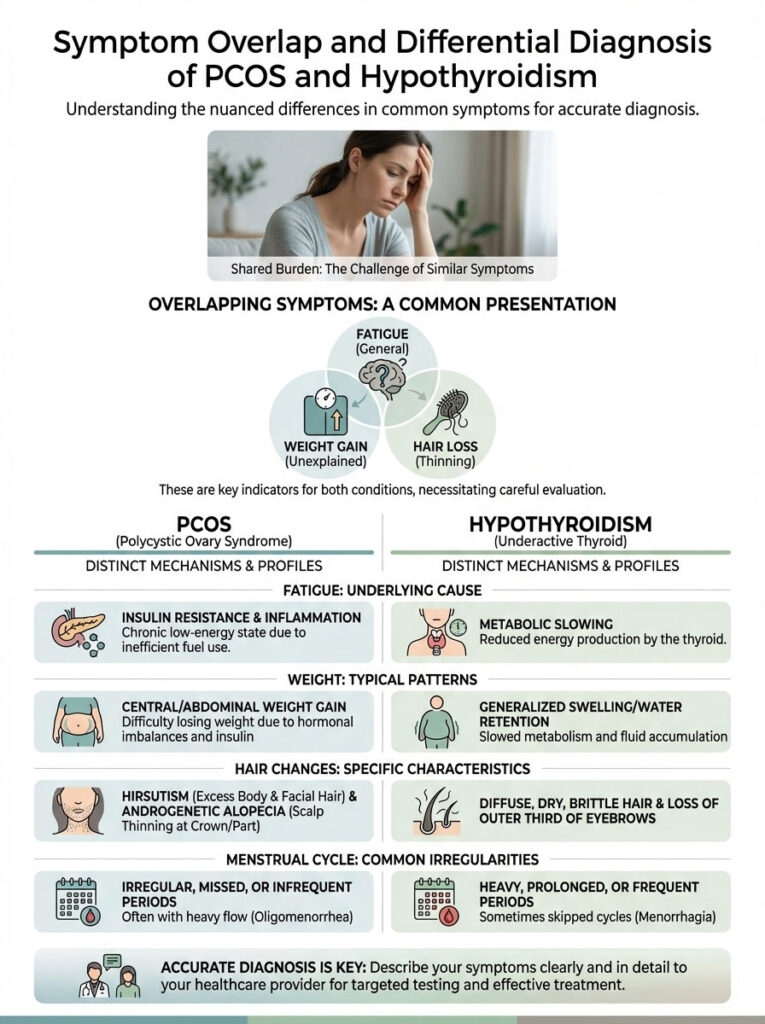

Symptom Overlap and Differential Diagnosis

One of the biggest hurdles in clinical care is the similarity of symptoms. PCOS and hypothyroidism look remarkably similar on the surface. Patients often bounce between specialists.

You might see a dermatologist for acne. You see a gynecologist for missed periods. You see a GP for fatigue. Rarely does anyone connect the dots.

Common clusters include fatigue and weight gain. Both conditions cause tiredness. However, the mechanism differs. Thyroid fatigue is metabolic slowing. PCOS fatigue is often due to insulin crashes.

Alopecia is another shared symptom. Both cause hair loss. Hypothyroidism tends to cause diffuse thinning all over the head. PCOS causes male-pattern thinning at the temples and crown.

To help you distinguish what might be driving your symptoms, review the comparison below. Understanding these nuances helps you describe your symptoms more accurately to your doctor.

Comparison Table: Distinguishing PCOS vs. Hypothyroidism

| Feature | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) | Hypothyroidism | The “Double Diagnosis” (Combined) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Profile | Weight gain (abdominal/visceral focus); difficulty losing weight due to insulin. | Generalized weight gain; fluid retention (myxedema); puffy face. | Severe, resistant weight gain; combination of fluid retention and visceral fat. |

| Hair Changes | Hirsutism (excess facial/body hair); androgenic alopecia (scalp thinning). | Dry, brittle hair; diffuse hair loss; loss of outer third of eyebrows. | Severe thinning combined with coarse facial hair growth. |

| Menstrual Cycle | Irregular periods (oligomenorrhea) or absent periods (amenorrhea). | Heavy, frequent periods (menorrhagia) or irregular cycles. | Highly erratic cycles; mix of heavy bleeding and long gaps between periods. |

| Skin Presentation | Oily skin; cystic acne; acanthosis nigricans (dark patches). | Dry, cool, pale skin; cracked heels; yellowish tint (carotenemia). | Combination of dry skin on the body with cystic acne on the jawline. |

| Energy Levels | “Tired but wired”; energy crashes after meals. | Chronic lethargy; brain fog; slow movement; cold intolerance. | Debilitating fatigue; unrefreshing sleep; severe brain fog. |

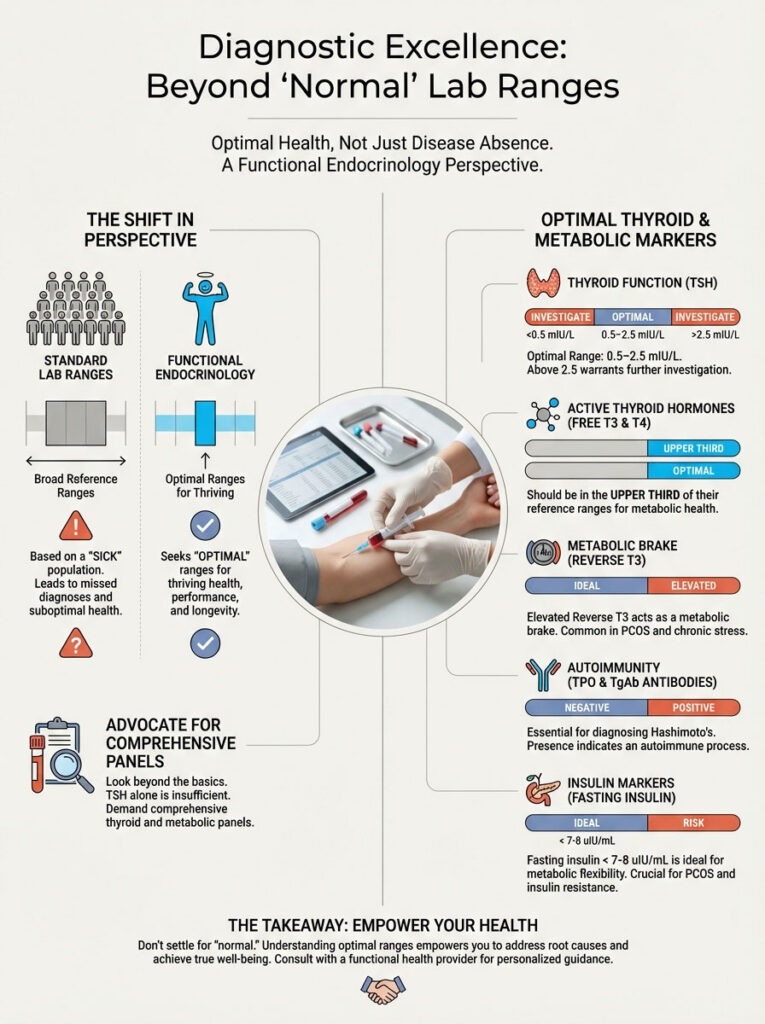

Diagnostic Excellence: Beyond “Normal” Lab Ranges

If you have been told your labs are “normal” but you still feel unwell, you are likely a victim of broad reference ranges. Standard lab ranges are based on a bell curve of the population visiting that lab.

Many of those people are already sick. In functional endocrinology, we look for optimal ranges. We look for the sweet spot where the body thrives, not just survives.

Optimal vs. Normal Targets

To effectively manage PCOS and hypothyroidism, you need to advocate for a full thyroid and metabolic panel. Do not settle for TSH alone. TSH is a pituitary hormone, not a thyroid hormone.

TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone): Labs often accept up to 4.5 or 5.0 mIU/L. However, functional medicine and fertility specialists target 0.5–2.5 mIU/L. Anything above 2.5 warrants investigation in a woman of reproductive age.

Free T3 & Free T4: These should fall in the upper third of the reference range. A low-normal Free T3 is a classic sign of poor conversion due to insulin resistance. If your T4 is normal but T3 is low, you have a conversion problem.

Reverse T3: This is a “metabolic brake.” It is often elevated in women with PCOS due to chronic stress and inflammation. It blocks the active T3 from doing its job. Think of it as a key that fits the lock but doesn’t turn.

Thyroid Antibodies (TPO & TgAb): These are non-negotiable. You can have normal TSH and still have antibodies attacking your thyroid. This confirms Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Knowing this changes your dietary strategy significantly.

Insulin Markers: Fasting insulin should ideally be < 7-8 uIU/mL. HOMA-IR is a calculation used to assess insulin resistance severity. Many doctors only check glucose. Glucose is a lagging indicator. Insulin rises years before glucose does.

Expert Insight: The Ultrasound Role

Blood work tells us about function, but ultrasound tells us about structure. An ovarian ultrasound is standard for PCOS (looking for follicle count), but request a thyroid ultrasound as well. A “heterogeneous echotexture” on a thyroid ultrasound is often the earliest sign of Hashimoto’s. It can appear even before antibodies spike significantly.

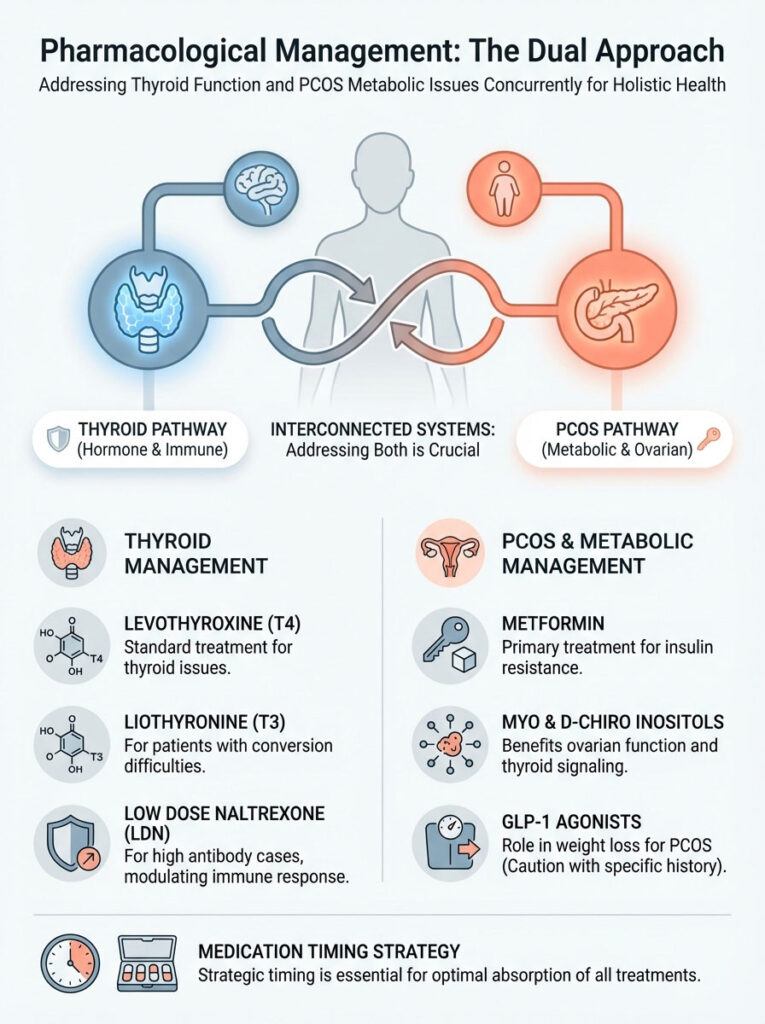

Pharmacological Management: The Dual Approach

Treating one condition without the other is like trying to drive a car with the parking brake on. You might move forward, but you will damage the engine. We need a strategy that addresses both the thyroid function and the metabolic chaos of PCOS.

Treating the Thyroid

Levothyroxine (T4) remains the standard of care. It provides the storage hormone your body is missing. However, for women with PCOS who struggle with conversion, T4 alone may not resolve symptoms.

In these cases, adding Liothyronine (T3) can be a game-changer. Brand names include Cytomel. This medication bypasses the liver conversion blockage caused by insulin resistance. It provides immediate active hormone to the cells.

For those with high antibodies, Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN) is an advanced functional option. It works by modulating the immune system. It increases endorphins, which can lower autoimmune attacks on the thyroid.

Treating the PCOS/Metabolic Component

Metformin is the frontline defense for insulin resistance. By sensitizing the body to insulin, Metformin lowers the insulin levels that are driving thyroid nodules and goiter. Interestingly, some studies suggest Metformin can independently lower TSH levels. It helps normalize thyroid function.

Inositols (Myo and D-Chiro) are powerful non-prescription tools. Myo-inositol improves ovarian function and egg quality. It also acts as a second messenger for TSH signaling. It helps the thyroid listen to the pituitary gland more effectively.

GLP-1 Agonists (like Semaglutide) are transforming obesity medicine. They are highly effective for weight loss in PCOS. However, there is a theoretical risk of medullary thyroid tumors (seen in rodents). Patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or MEN2 syndrome must avoid them.

Medication Timing Strategy

Absorption is everything. You can be prescribed the perfect dose, but if you take it with your latte, you aren’t absorbing it. The stomach environment dictates the efficacy of your thyroid medication.

Review the table below to ensure you aren’t accidentally neutralizing your treatment.

| Medication/Supplement | Primary Purpose | Interaction Warning | Optimal Timing Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levothyroxine (T4) | Thyroid hormone replacement. | Absorption is blocked by calcium, iron, coffee, and food. | Take immediately upon waking on an empty stomach with water only. Wait 60 mins to eat. |

| Metformin | Insulin sensitizer. | May cause GI upset; rarely impacts thyroid absorption directly but best separated. | Take with the largest meal of the day (dinner) to reduce nausea and improve compliance. |

| Iron Supplements | Treating ferritin deficiency (hair loss). | Binds to thyroid medication, rendering it ineffective. | Take at least 4 hours apart from thyroid medication (e.g., at lunch or dinner). |

| Calcium / Dairy | Bone health. | Significantly reduces thyroid hormone absorption. | Maintain a 4-hour gap from thyroid medication. |

| Myo-Inositol | Ovarian function & insulin. | Synergistic with thyroid meds; helps TSH signaling. | Can be taken morning or night; generally safe to take with food. |

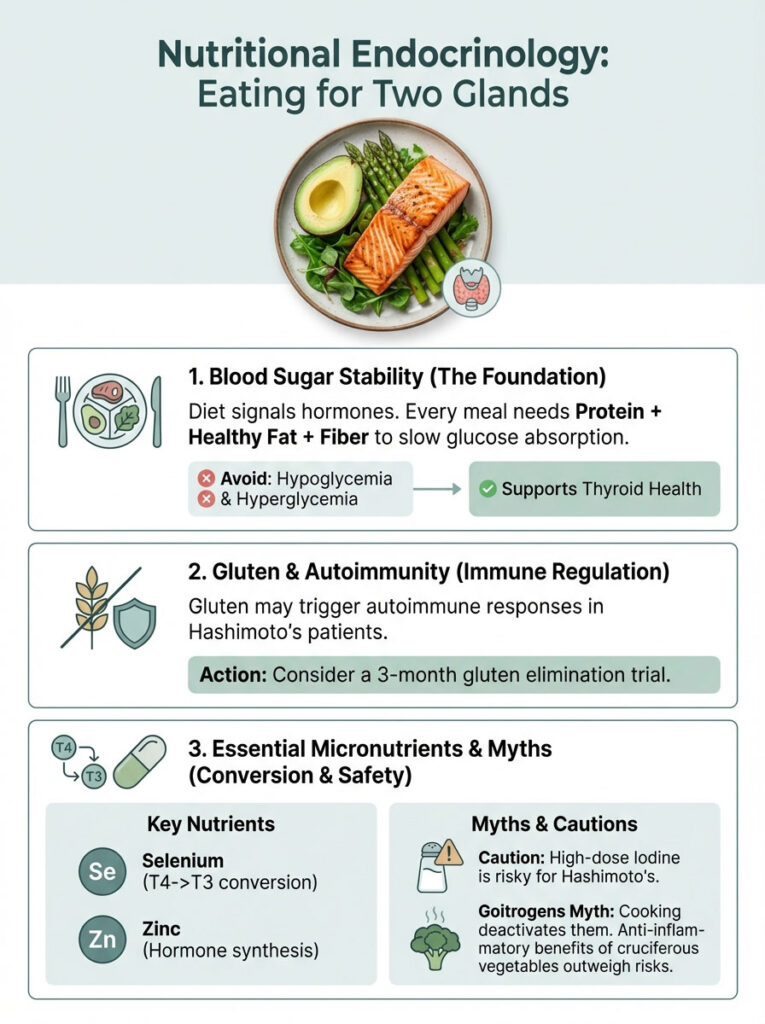

Nutritional Endocrinology: Eating for Two Glands

Your diet acts as a daily signal to your hormones. To manage PCOS and hypothyroidism, the goal is blood sugar stability and immune regulation. You are not just counting calories. You are feeding your biochemistry.

The Glucose-Thyroid Balance

Blood sugar stability is the foundation of thyroid health. When your blood sugar drops too low (hypoglycemia) or spikes too high (hyperglycemia), your adrenal glands release cortisol.

Cortisol suppresses the pituitary gland. This lowers TSH production. To prevent this, every meal must contain protein, healthy fat, and fiber. This slows glucose absorption.

Keeping insulin steady keeps cortisol steady. This allows the thyroid to function without emergency brakes. Avoid naked carbohydrates. Never eat an apple alone; pair it with almonds.

The Gluten & Autoimmunity Debate

This is a polarizing topic. However, the clinical data is compelling for Hashimoto’s patients. The protein structure of gliadin (a component of gluten) closely resembles thyroid tissue.

This leads to a phenomenon called “molecular mimicry.” When you eat gluten, your immune system attacks it. Because the thyroid looks similar, the immune system attacks the gland too.

For patients with positive TPO antibodies, we strongly recommend a 3-month strict gluten elimination trial. Many patients report a significant drop in antibodies. They also report reduced bloating and better energy.

Micronutrients for Conversion

Your thyroid needs specific raw materials to function. It is like a factory. If you don’t deliver the steel, you can’t build the car.

Selenium: This mineral is vital. It powers the enzyme that converts T4 to T3. It also helps lower TPO antibodies. Two to three Brazil nuts a day can provide a sufficient therapeutic dose.

Zinc: This is essential for hair growth and thyroid hormone synthesis. Zinc deficiency is common in women on birth control pills. It is also depleted by stress.

Iodine Caution: While the thyroid needs iodine, supplementing with high doses without testing can be dangerous. It acts like throwing gasoline on a fire for Hashimoto’s. It can potentially trigger a “thyroid storm” or worsen autoimmunity.

Goitrogens: Fact vs. Fiction

You may have heard that people with thyroid issues should avoid broccoli, kale, and spinach. They are labeled “goitrogenic” (thyroid-suppressing). This is largely a myth in the context of a modern diet.

The goitrogenic compounds are deactivated by cooking. You would need to eat massive amounts of raw kale daily to impact your thyroid. The anti-inflammatory benefits of these vegetables far outweigh the theoretical risks. Steam your cruciferous vegetables and enjoy them.

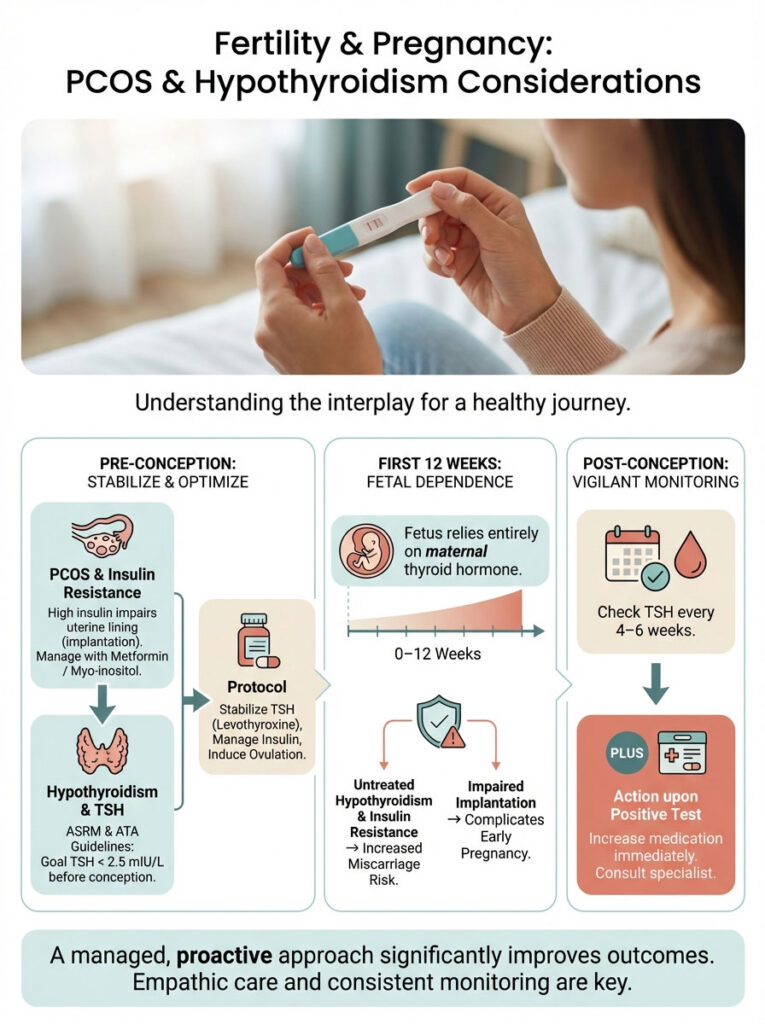

Fertility and Pregnancy Considerations

For many women, the diagnosis of PCOS and hypothyroidism comes during the struggle to conceive. The stakes here are high. However, the path is clear.

ASRM & ATA Guidelines

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and the American Thyroid Association (ATA) agree regarding thyroid targets. TSH targets must be stricter for conception. We aim for a TSH < 2.5 mIU/L prior to conception and throughout the first trimester.

This is because the fetus relies entirely on the mother’s thyroid hormone for the first 12 weeks of development. The baby does not have a working thyroid yet. If you are low, the baby is low.

The Risk of Miscarriage

Untreated hypothyroidism and unmanaged insulin resistance both independently increase the risk of miscarriage. The combination creates a hostile environment for implantation.

High insulin impairs the uterine lining. It makes implantation difficult. Meanwhile, low thyroid hormone threatens fetal neural development. This combination is a frequent cause of recurrent pregnancy loss.

The Protocol for Conception

If you are trying to conceive, the order of operations matters. You cannot force ovulation if the metabolic environment is unsafe.

First, stabilize TSH. Use Levothyroxine to get TSH below 2.5 mIU/L. Second, manage insulin. Use Metformin or Myo-inositol to lower miscarriage risk.

Third, induce ovulation. Once the metabolic environment is safe, medications like Letrozole are used. Finally, monitor closely. Once pregnant, thyroid demand increases by 50%. You must check TSH every 4–6 weeks. Expect to increase your medication dose immediately upon a positive pregnancy test.

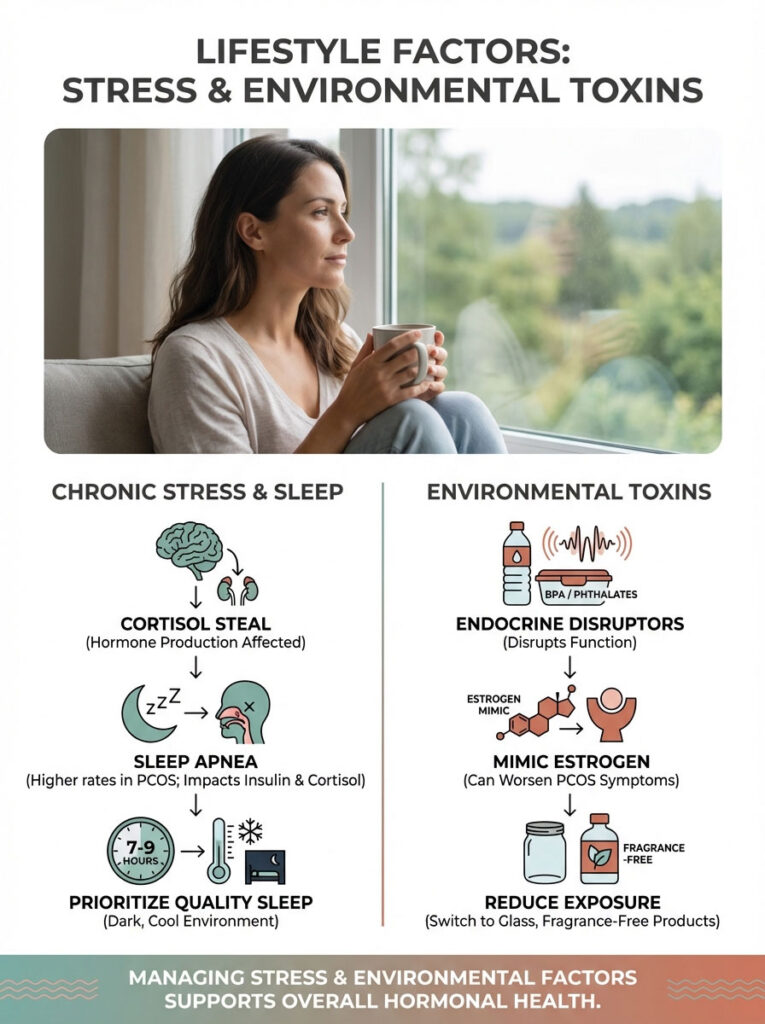

Lifestyle Factors: Stress and Environmental Toxins

We cannot medicate our way out of a high-stress lifestyle. Chronic stress leads to the “Cortisol Steal.” When the body is pumping out cortisol to handle stress, it downregulates the production of sex hormones and thyroid hormones.

This is an ancient survival mechanism. If you are running from a predator, your body pauses reproduction. It slows metabolism to save energy. Modern stress triggers this same ancient switch.

Sleep Hygiene and Apnea

Sleep is non-negotiable. Women with PCOS have a much higher rate of sleep apnea. If you snore or wake up gasping, get tested.

If you are not getting oxygen at night, your insulin resistance worsens. Your cortisol stays high. This suppresses your thyroid function the next day. Prioritize 7-9 hours of quality sleep in a cool, dark room.

Endocrine Disruptors

Finally, be aware of environmental toxins. Chemicals like BPA (in plastics) and Phthalates (in fragrances) are endocrine disruptors. They bind to thyroid and estrogen receptors.

They can block real hormones from doing their job. They can also mimic estrogen, worsening the dominance seen in PCOS. Switching to glass containers and fragrance-free products is a simple but effective way to reduce the toxic load on your glands.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The link between PCOS and hypothyroidism is not a coincidence. It is a physiological reality driven by insulin, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Treating one without the other leads to partial recovery at best.

The “vicious cycle” is real. Insulin resistance hurts the thyroid. A slow thyroid hurts insulin sensitivity. However, this cycle can be broken.

By optimizing TSH levels, addressing insulin resistance with Metformin or inositols, and adopting a nutrient-dense diet, you can restore metabolic flexibility. Do not accept “normal” for an answer. Advocate for full panels. Check your antibodies. View your nutrition as a medical intervention.

If you suspect you are battling this double diagnosis, consult with a reproductive endocrinologist or an integrative practitioner. You need someone who understands the nuance of these connecting pathways. Your health is worth the investigation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are PCOS and hypothyroidism often diagnosed together?

These conditions are linked through shared metabolic pathways involving insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. PCOS patients are statistically three times more likely to develop Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, often due to a biochemical cross-talk where hyperinsulinemia impairs thyroid function and estrogen dominance triggers autoimmune responses.

How does hypothyroidism worsen PCOS symptoms like acne and hirsutism?

Hypothyroidism reduces the liver’s production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), which acts as a “sponge” for excess androgens. When SHBG levels drop, more testosterone remains “free” and active in the bloodstream, directly exacerbating cystic acne, male-pattern hair growth, and androgenic alopecia.

What is the optimal TSH range for women with PCOS and fertility concerns?

While standard laboratories may accept TSH levels up to 4.5 mIU/L, functional endocrinology and fertility guidelines recommend an optimal range of 0.5 to 2.5 mIU/L. Maintaining a TSH below 2.5 is critical for ensuring consistent ovulation and reducing the risk of early pregnancy loss.

Can insulin resistance lead to thyroid nodules or goiter?

Yes, insulin acts as a potent growth factor for thyroid tissue; therefore, the hyperinsulinemia common in PCOS can stimulate the thyroid gland to increase in volume. This often results in the formation of thyroid nodules or a goiter, which is why we frequently see polycystic ovarian morphology and thyroid structural changes coexisting.

Why do my thyroid labs look normal even though I have PCOS and fatigue?

Standard labs often only check TSH and T4, missing the “cellular hypothyroidism” caused by poor T4 to T3 conversion. Systemic inflammation from PCOS can suppress the deiodinase enzyme, leading to low active T3 levels or elevated Reverse T3, which acts as a metabolic brake even when TSH appears within range.

What is the link between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and PCOS?

The link is primarily autoimmune and inflammatory, with roughly 25% to 30% of PCOS patients testing positive for TPO antibodies. Estrogen dominance in PCOS can stimulate B-cell activity, potentially “turning on” the genetic markers for Hashimoto’s and leading to an autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland.

Is a gluten-free diet necessary for managing PCOS and hypothyroidism?

For patients with positive TPO or TgAb antibodies (Hashimoto’s), a gluten-free trial is highly recommended due to molecular mimicry. The protein structure of gluten resembles thyroid tissue, and removing it can significantly reduce the autoimmune attack, systemic inflammation, and the “brain fog” associated with both conditions.

How does Myo-inositol help both the thyroid and the ovaries?

Myo-inositol serves as a second messenger for both insulin and TSH signaling. By improving the thyroid’s ability to “listen” to the pituitary gland and enhancing insulin sensitivity in the ovaries, it helps restore regular ovulation while supporting more efficient thyroid hormone production.

What are the risks of having both PCOS and hypothyroidism during pregnancy?

The combination of low thyroid hormone and high insulin creates a high-risk environment for recurrent pregnancy loss and impaired fetal neural development. Because the fetus relies on maternal T4 for the first trimester, thyroid medication doses must often be increased immediately upon a positive pregnancy test to ensure a healthy gestation.

Why must iron supplements be taken separately from thyroid medication?

Iron, calcium, and caffeine significantly impair the absorption of Levothyroxine in the gut by binding to the hormone. To ensure therapeutic efficacy, you should take thyroid medication on an empty stomach and wait at least four hours before taking iron supplements or consuming dairy products.

Can Metformin help improve thyroid function in PCOS patients?

Clinical research suggests that Metformin can independently lower TSH levels in patients with both PCOS and hypothyroidism. By reducing the hyperinsulinemia that drives thyroid inflammation, Metformin helps stabilize the metabolic environment, making thyroid hormone replacement therapy more effective.

What specific blood tests should I request for a full endocrine evaluation?

A comprehensive panel should include TSH, Free T4, Free T3, Reverse T3, and thyroid antibodies (TPO and TgAb). Additionally, you must assess metabolic health using fasting insulin and the HOMA-IR calculation, as glucose alone is a lagging indicator of the insulin resistance driving your symptoms.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The complex interaction between PCOS and hypothyroidism requires personalized clinical supervision. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional, such as a reproductive endocrinologist or thyroid specialist, before starting new medications, supplements, or making significant dietary changes.

References

- American Thyroid Association (ATA) – thyroid.org – Clinical guidelines for the management of hypothyroidism and thyroid function targets for pregnancy.

- The Endocrine Society – endocrine.org – Research on the pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and its metabolic co-morbidities.

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) – asrm.org – Guidance on TSH targets for women struggling with infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss.

- Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – “The Prevalence of Thyroid Disorders in Women with PCOS” – A peer-reviewed study detailing the 3x increased risk of Hashimoto’s in PCOS patients.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) – nichd.nih.gov – Data regarding insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and its impact on thyroid nodule formation.

- PCOS Challenge: The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association – pcoschallenge.org – Statistics on the prevalence of autoimmune markers and subclinical hypothyroidism in the PCOS population.